Ida B. Wells-Barnett

In 1862, Ida B. Wells-Barnett was born in Holly Springs, Mississippi. She was born into slavery and later emancipated with her parents at the conclusion of the Civil War.

Wells-Barnett was a journalist, anti-lynching activist, women’s suffragist, and early civil rights movement leader.

Wells-Barnett authored A Red Record, a book that provided the history and statistical data on the lynching of African Americans in the United States during the late nineteenth century.

“When I present our cause to a minister, editor, lecturer, or representative of any moral agency, the first demand is for facts and figures.”

Chapter 10, The Red Record

“When the lives of men, women and children are at stake, when the inhuman butchers of innocents attempt to justify their barbarism by fastening upon a whole race the obloquy of the most infamous of crimes, it is little less than criminal to apologize for the butchers today and tomorrow repudiate the apology by declaring it a figure of speech.”

Chapter 8, The Red Record

Early Life

Ida B. Wells-Barnett was born on July 16, 1862, in Holly Springs, Mississippi. She was born into slavery during the Civil War, a period defined by the fight to abolish slavery and debates over the citizenship rights of African Americans. In 1865, Wells-Barnett and her parents, Elizabeth Warrenton Wells and James Wells, were emancipated from slavery via the Emancipation Proclamation.

The conclusion of the Civil War ushered in the Reconstruction era. Wells-Barnett’s parents were hopeful about the future for African Americans and instilled the value of education in their children (T. Burroughs, Chap. 1). Her father was a trustee at Rust College (formerly Shaw University), where she attended until 1880, dropping out after she passed her teaching exam.

In the fall of 1878, Wells-Barnett’s parents died in a yellow fever epidemic. At age sixteen, she became the primary caretaker for her six remaining siblings. She became a schoolteacher to support her family and eventually moved to Memphis, where she worked in Shelby County, Tennessee.

The Brilliant Iola: Black Journalism

On May 4, 1884, Wells-Barnett undertook her commute to Shelby County on the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad. She purchased a first-class ticket to sit in the ladies’ car, but the conductor ordered her to move to the smoking car. After being forcefully dragged off the train, Wells-Barnett noted that the white passengers, “...stood on the seats so that they could get a good view and continued applauding the conductor for his brave stand” (I. Wells 17). She retaliated by suing the Ohio railway company and initially won compensation for the harassment. However, the Tennessee state supreme court later reversed the decision. Still, the case reflected Wells-Barnett’s early commitment to legal equity.

Wells-Barnett’s journalism career began in Memphis. She became the editor of a local newspaper, The Evening Star, and a writer for The Living Way under the pen name “Iola.” Her editorials addressed the racial issues African Americans faced daily. Her writing earned her national recognition and the nicknames “Princess of the Press” and “The Brilliant Iola.”

In 1889, she joined the Free Speech and Headlight as a partner and editor. Her desire to own a newspaper grew during this period of increased writing activity (I. Wells 32). Two years later, she exposed the poor conditions of the Memphis public school system. As a result, she was fired from her position as a schoolteacher, prompting her to pursue journalism full time.

Her writing took a pivotal turn in 1892 when her close friend Thomas Moss was lynched (T. Burroughs, Chap. 3). Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Henry Steward—owners of the People’s Grocery store in Memphis—were lynched for threatening the economic dominance of a local white grocer. Wells-Barnett investigated the incident and reported her findings in Free Speech, exposing inconsistencies in the official narrative and highlighting Memphis’s racial prejudice. In response, a white mob set fire to the Free Speech office. Wells-Barnett, who was visiting Oklahoma at the time, was forced to leave Memphis but remained firmly committed to anti-lynching activism (I. Wells 56).

Lynching became the center of her research. She continued investigating cases across the eastern seaboard, traveling and writing about injustices along the way. In 1892, she published the pamphlet Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, which described how lynch mobs formed and the common excuses white officials used to justify these acts. The following year, she was hired by The Chicago Inter-Ocean to investigate lynching in the American South. She went undercover and published her findings in the newspaper.

Domestic Efforts and Abroad Lectures

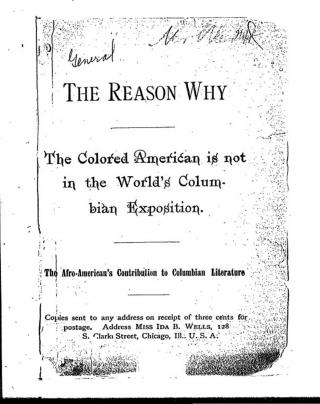

In 1893, Wells-Barnett arrived in Chicago, Illinois, after briefly lecturing overseas—the same year the World’s Columbian Exposition was held in the city. The United States’ representatives largely excluded the Black community from participating in the “White City” fairgrounds and rejected proposals for increased African American representation (A. Massa 332). Wells-Barnett, Frederick Douglass, and other Black leaders responded by highlighting the racial inequality embedded in the exposition.

Wells-Barnett proposed publishing a record that documented African American life after Emancipation. She invited contributions from other interested members and raised the necessary funds to bring the project to life (Massa 336). The result was the pamphlet The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition, published in three languages. It detailed the daily oppression African Americans faced. Wells-Barnett distributed the pamphlet at the Haitian government booth, where Frederick Douglass had been invited as a representative.

Above:The Reason Why pamphlet cover, published by Ida B. Wells, 1893.

[New York Public Library Digital Collections]

By 1894, she had returned overseas, spreading awareness of lynching and racial oppression in the United States. She lectured throughout the United Kingdom, addressing misconceptions about lynching and inspiring the formation of the London Anti-Lynching Committee. She also criticized the lack of support from white women in the suffrage movement.

Black Feminism

Upon returning to Chicago, Wells-Barnett was welcomed by the Ida B. Wells Club, a women’s club named in her honor. Active in women’s rights issues, she consistently advocated for the rights of women, Black women, and the broader Black community. This often caused friction within some white-dominated suffrage organizations. Her relationship with Susan B. Anthony reflected these tensions—she respected Anthony’s pioneering work but criticized her failure to prioritize Black women’s concerns in order to maintain white women’s support (T. Burroughs, Chap. 9).

Wells-Barnett helped found several suffrage organizations for Black women, including the League of Colored Women, the National Association of Colored Women, and the Alpha Suffrage Club, which uplifted the concerns of working-class women regarding race, gender, and class.

On June 27, 1895, she married attorney Ferdinand L. Barnett, the owner of the Conservator newspaper. Wells-Barnett later became the editor and sole owner after purchasing her husband’s shares. Even with the birth of her first child, she continued her political work and research. She traveled with her nursing baby, supported by her husband and the Women’s State Central Committee, which employed a nurse to assist during her lectures (I. Wells 206).

Anti-Lynching Activism and Black Leadership

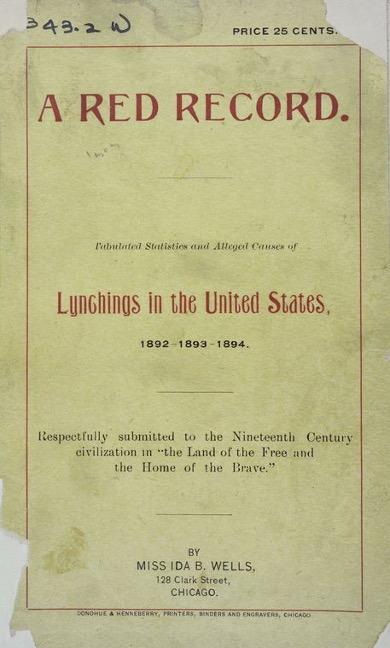

Wells-Barnett’s anti-lynching efforts culminated in 1895 with the publication of A Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynchings in the United States, 1892–1893–1894. In 100 pages, she provided a history and statistical record of lynchings in the United States. She urged readers to consider how they could contribute to the anti-lynching cause and pursue justice (I. Wells-Barnett 144). The book brought years of research and journalism to the public, promoting awareness and the fight for racial equality.

Above: Original cover of A Red Record by Ida B. Wells-Barnett, 1895.

[New York Public Library Digital Collections]

In 1909, she attended the National Negro Conference in New York City and presented “Lynching, Our National Crime,” a report compiling 20 years of research. It was at this conference that the “Founding Forty” of the NAACP were selected. Despite her leadership, Wells-Barnett was excluded from the list. That same year, she founded the Negro Fellowship League in Chicago—a social service center that offered housing, employment assistance, education, and legal counseling. The League represented her commitment to local leadership and to the well-being of working-class Black communities.

Later Years

Wells-Barnett continued her activism, journalism, and suffrage work throughout her later years. In 1915, she joined a committee led by William Monroe Trotter to present concerns about segregation to President Woodrow Wilson. She told the president, “...there were more things going on in the government than he had dreamed of in his philosophy, and we thought it our duty to bring to his attention that phase of it which directly concerned us” (I. Wells 321).

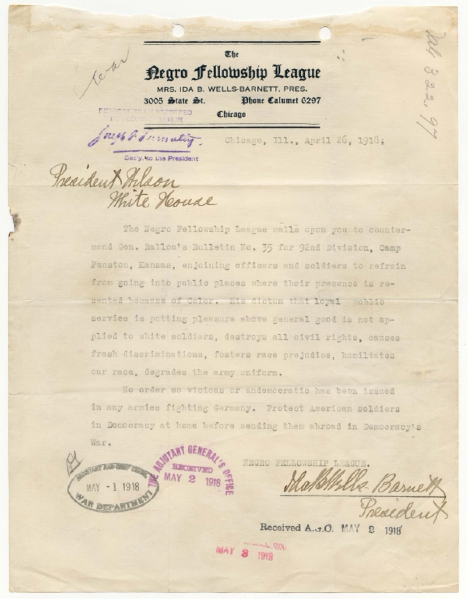

In 1918, she brought national attention to the discrimination African American soldiers faced during and after World War I. She set up memorials and wrote a letter to President Wilson, condemning the mistreatment Black soldiers endured.

Above: Wells-Barnett’s letter to President Woodrow Wilson, 1918.

[National Archives Catalog]

Within the twentieth-century suffrage movement, she pushed for Black women’s voting rights and political representation. At the 1913 Women’s Procession March, Black suffragists were told to walk at the back to avoid offending Southern white women. Wells-Barnett refused and marched alongside white suffragists to integrate the demonstration (T. Burroughs, Chap. 10). She later ran for a delegate seat at the Republican National Convention in 1918 and for the Illinois State Senate in 1930. Though unsuccessful, her commitment to political rights for Black women and the broader Black community remained strong.

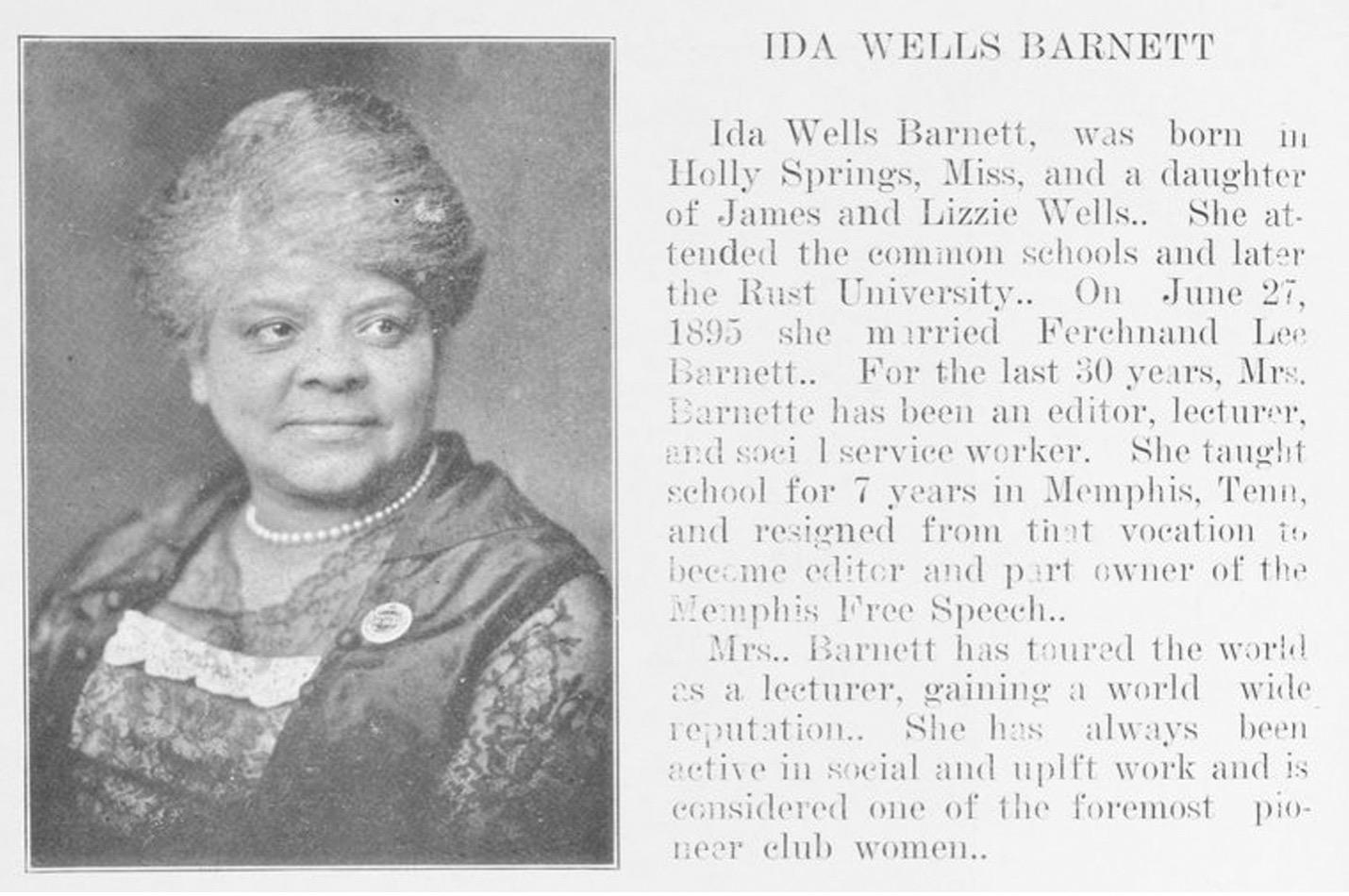

Above: Wells-Barnett’s page in The story of the Illinois Federation of Colored Women's Club, 1922.

[New York Public Library Digital Collections]

On March 15, 1931, Ida B. Wells-Barnett died from kidney disease. A respected leader in Chicago’s Black community, she left behind a legacy that was not fully recognized until the publication of her autobiography in 1970. Although she did not live to witness the Civil Rights Movement, her anti-lynching activism and journalism laid the foundation for its radical spirit, reflecting the power of collective action in the Black community.

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Newspaper Clipping July 14, 1917

Caption: “Mrs. Ida B. Wells-Barnett.”

Analysis Questions

- Describe the image of Wells-Barnett included in this newspaper clipping, what do you notice? What sort of image is it?

- When was this newspaper published? What was happening in this period?

- How is Wells-Barnett being described?

- Based on your knowledge of Wells-Barnett, is the comparison to Joan D’Arc an accurate one? Why or why not? If you could compare her to another historical figure, who would you include?

Educator Notes

Ida B. Wells-Barnett is in the bottom right corner of the newspaper.

Text of Newspaper: “One of the greatest champions of the civil and political status of the Colored people in this country who had been designated as the Joan D’Arc of the Afro-American race.”

Educators can use the Teaching with Primary Sources Teacher’s Guide: Analyzing Newspapers to build activities and encourage students to reflect on the public perception of Ida B. Wells-Barnett during the early twentieth century.

Letter from Ida B. Wells-Barnett to President Woodrow

Caption: “In this letter, President of the Negro Fellowship League, Mrs. Ida B. Wells-Barnett writes to President Woodrow Wilson asking him to revoke the order urging officers and soldiers to refrain from going into public places where their presence is resented because of color.”

Analysis Questions

- Who is addressed in this letter?

- What concerns are presented in this letter? How does Wells-Barnett’s address these concerns?

- How does the historical connect inform the reader on the condition of African American soldiers during this period?

Educator Notes

Text of Letter: “The Negro Fellowship League calls upon you to countermand Gen. Ballou’s Bulletin No. 35 for 92 Division, Camp Funston, Kansas, enjoining officers and soldiers to refrain from going into public places where their presence is resented because of Color. His dictum that loyal public service is putting pleasure above general good is not applied to white soldiers, destroys all civil rights, causes fresh discrimination, fosters race prejudice, humiliates our race, degrade the army uniform. No order so vicious or undemocratic has been issued in any armies fighting Germany. Protect American soldiers in Democracy at home before sending them abroad in Democracy’s War.”

Educators can use the Teaching with Primary Sources Teacher’s Guide: Analyzing Primary Sources to encourage a close readings of first-hand narratives and explore Wells-Barnett’s writings about equal rights for African Americans.

Still Image of Ida B. Wells-Barnett

Caption: “United States Atrocities: Lynch Law, [Title Page]”

Analysis Questions

- What do you notice from this title page?

- What was Wells-Barnett’s purpose in creating this primary source? What subjects does she appear to address?

- Are there other primary sources by Wells-Barnett that convey similar themes? What differences does this primary source contain?

Educator Notes

Educators can use the Teaching with Primary Sources Teacher’s Guide: Analyzing Primary Sources and the Library of Congress Finding Primary Source Guide to encourage inquiry-based searches and comparisons of Wells-Barnett’s anti-lynching publications.

- Burroughs, Todd Steven. Warrior Princess: A People's Biography of Ida B. Wells. New York: Diasporic Africa Press, 2017

- Foner, Eric, and Donald Corren. The second founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction remade the Constitution. Prince Frederick, MD: Recorded Books, 2019.

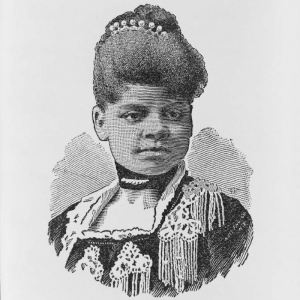

- Citation for cover image: “[Ida B. Wells, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing slightly right],” 1891. Illustration. Washington D.C., Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Miscellaneous Items in High Demand. Accessed January 2025. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3c07756/.

- Massa, Ann. “Black Women in the ‘White City.’” Journal of American Studies 8, no. 3 (December 1974): 319–37. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021875800015917.

- Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library. “Ida Wells Barnett.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed January 13, 2025. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dd-ebed-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

- Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library. “The Reason why the colored American is not in the World’s Columbian Exposition [microform] : the Afro-American's contribution to Columbian literature.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed January 2025. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/92e603ba-345d-92b1-e040-e00a18063488

- Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. “A red record” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed January 13, 2025. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-8dbd-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

- Wells-Barnett, Ida B. “Letter from Ida B. Wells-Barnett to President Woodrow Wilson Protesting General Ballou's Bulletin Number 35 for the 92nd Division, Camp Funston, Kansas,” 1918. National Archives Catalog, Combat Divisions; Records of the 1st-20th, 26th-42d, and 76th-103d Divisions, 1917-19

- Wells-Barnett, Ida B. The red record. New York, NY: Open Road Integrated Media, 2015.

- Wells, Ida B. Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells. Edited by Alfreda M. Duster. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020.

MLA – Gonzalez, Corina. “Ida B. Wells-Barnett.” National Women’s History Museum, 2024. Date accessed.

Chicago – Gonzalez, Corina. “Ida B. Wells-Barnett.” National Women’s History Museum. 2024. www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/ida-bells-wells-barnett.

- Ida B. Wells | A Chicago Stories Special Interactive Website

- Public Broadcasting System (PBS) – Ida B. Wells

- Women's History Minute: Ida B. Wells | National Women’s History Museum

- African American Reformers: The Club Movement | National Women’s History Museum

- National Association of Colored Women | National Women’s History Museum

- Votes for Women means Votes for Black Women | National Women’s History Museum

Susan B. Anthony

This biography is sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University. Content created and featured in partnership with the TPS program does not indicate an endorsement by the Library of Congress.

For further information or questions, please contact [email protected].

Harriet Tubman

This biography is sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University. Content created and featured in partnership with the TPS program does not indicate an endorsement by the Library of Congress.

For further information or questions, please contact [email protected].