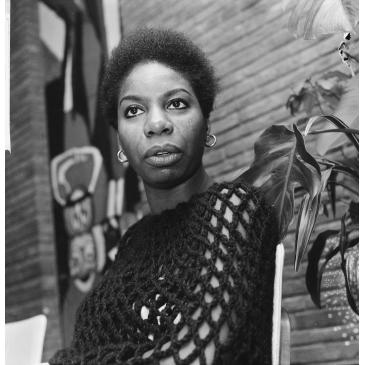

Toshiko Akiyoshi

Toshiko Akiyoshi changed the face of jazz music over her sixty-year career. As one of few women and Asian musicians in the jazz world, Akiyoshi infused Japanese culture, sounds, and instruments into her music. As a pianist, bandleader, and composer-arranger, Akiyoshi cemented her place as one of the most important jazz musicians of the twentieth century.

Toshiko Akiyoshi was born on December 12, 1929, in Darien, Manchuria. Historically an area of China, many world powers fought to control Manchuria during the twentieth century. From 1932-1945, the Japanese held Manchuria under colonial control. At the end of World War II, the Japanese in Manchuria—including Akiyoshi’s family—were forced out.

The family moved back to occupied Japan, where they experienced the hardships of postwar life. In an interview, Akiyoshi noted that when the family came back, her “parents lost everything.” While Akiyoshi had been able to play piano in Manchuria, her parents were now unable to provide her with an instrument. Since Japan was still under occupation, there were many clubs that catered to both soldiers and the local community. The clubs needed musicians to entertain not only the foreign troops but the Japanese who wanted to dance and listen to music. To keep playing piano, the teenaged Akiyoshi got her first job playing in the clubs and in small combos. By 1951, she was playing piano professionally and leading her own jazz group.

In 1952, pianist Oscar Peterson discovered Akiyoshi while he was on a Jazz at the Philharmonic tour of Japan. After hearing her play in a Tokyo nightclub, Peterson persuaded producer Norman Granz to record her on his Verve label. This recording became Akiyoshi’s big break. After this opportunity, Akiyoshi came to the United States in 1956 to begin studying at the Berklee School of Music in Boston. With her enrollment, she became the first Japanese musician at the school.

In 1959, she moved to New York City and established a reputation as a fine “bebop” (a style of jazz popularized in the 1940s in the U.S.) player. She played in clubs such as Birdland, Village Gate, Five Spot, and Half Note. She remembered facing discrimination in the jazz world because she was a woman and Asian. In an interview, Akiyoshi recalled hearing people ask “’Japanese play jazz, really?’” and, when it came to her being female, she described it as a “‘Really, really?’ kind of thing.’” In 1959, she also married her first husband, saxophonist Charlie Mariano; the two formed a quartet. In the 1960s, Akiyoshi continued making her mark on the jazz world. She began showing her talent as a composer-arranger for big bands and worked with Charles Mingus in 1962.

By 1973, Akiyoshi had moved to Los Angelas with her second husband, saxophonist, and flutist Lew Tabackin. That same year, Akiyoshi formed her first jazz orchestra—the Toshiko Akiyoshi Jazz Orchestra. Tabackin, who was playing with The Tonight Show band, helped fill the 16-piece orchestra with some of the best studio musicians in town. The Toshiko Akiyoshi Jazz Orchestra went on to have great success, winning the DownBeat Critic’s Poll and best jazz album of the year for Long Yellow Road by Stereo Review in 1976. Akiyoshi also began to branch out musically. Since all of the saxophone players could also play flute, Akiyoshi thought she could write a woodwind section for the band. In the 1970s, she also began introducing Japanese themes and instruments into her compositions and arrangements. All became her trademarks.

In 1982, Akiyoshi and her husband moved back to New York and restarted their band with New York musicians. They continued to enjoy critical success. The band debuted at Carnegie Hall as part of the 1983 Kool Jazz Festival and went on to record 22 albums and receive 14 Grammy nominations. Akiyoshi became the first woman to place first in the Best Arranger and Composer category in the DownBeat Readers’ Poll. Among her other notable honors are the Shijahosho (1999, from the Emperor of Japan); the Japan Foundation Award, Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Rosetta (2004, from the Emperor of Japan); the Asahi Award (2005, from the Asahi Shimbun newspaper); and NEA Jazz master, American jazz’s highest honor (2007). Her autobiography, Life with Jazz (1996), is in its fifth printing in Japanese.

In 2003, Akiyoshi disbanded her orchestra to focus on piano. She said in an interview, “it has been 60 years since I discovered jazz and made it my lifetime work. I am so gratified to be recognized for my endeavors especially my infusing of Japanese culture into the jazz world, making it ever more universal.”

“Toshiko Akiyoshi,” National Endowment for the Arts, https://www.arts.gov/honors/jazz/toshiko-akiyoshi

Joseph Paice, “Toshiko Akiyoshi,” World of Jazz.org, 2020, https://worldofjazz.org/toshiko-akiyoshi/

Tom Vitale, “Toshiko Akiyoshi’s Jazz Orchestra Brought the Club to Concert Halls,” All Things Considered, NPR, February 16, 2016, https://www.npr.org/2016/02/16/466930497/toshiko-akiyoshis-jazz-orchestra-brought-the-club-to-concert-halls

MLA – “Toshiko Akiyoshi” National Women’s History Museum, 2022. Date accessed.

Chicago – “Toshiko Akiyoshi.” National Women’s History Museum. 2022. www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/toshiko-akiyoshi.

Photo Credit: Brian McMillen. - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Toshiko_Akiyoshi.jpg, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, “Manchuria,” Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/place/Manchuria

Nat Hentoff, “A Japanese Jazz Musician Tackles the Daunting Subject of Hiroshima,” The Wall Street Journal, August 21, 2003, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB106143400299586200 (paywall)

“Toshiko Akiyoshi,” Discogs.com, https://www.discogs.com/artist/503241-Toshiko-Akiyoshi