Anna Julia Cooper

Anna Julia Cooper was born into enslavement; once freed, she set her sights on receiving a robust education

Cooper advocated for better educational opportunities her entire life -- not just for herself, but others as well

Cooper was a groundbreaking educator, activist, and author who changed the trajectories of many young Black women

"The cause of freedom is not the cause of a race or a sect, a party or a class—it is the cause of humankind, the very birthright of humanity,” 1892, A Voice from the South by Anna Julia Cooper

Early Life

Anna Julia Cooper was born into enslavement in 1858 in Raleigh, North Carolina. Her mother was Hannah Stanley Haywood, and her enslaver, Fabius J. Haywood, was said to be her father. Cooper also had two brothers, Andrew and Rufus. Following her emancipation at age 9, Cooper set her sights on receiving an education. The Freedmen’s Bureau – which provided “food, shelter, clothing, medical services and land to displaced Southerners including newly freed African Americans” - assisted Cooper in finding schooling (United States Senate). In 1867, she became a student at the Saint Augustine Normal and Collegiate Institute in Raleigh, North Carolina, a school built specifically to educate formerly enslaved children (Douglass Day).

While her attendance was already a remarkable achievement, gender discrimination from the school’s administration presented Cooper with roadblocks. Her protests granted her entry into St. Augustine’s Normal School’s Greek and Latin course, which were previously male-designated courses (National Museum of African American History and Culture). The success of protesting these inequities as early as the age of 9 placed her on the lifelong path of advocating for gender equality. At the age of 11, Cooper was granted the role of scholarship-teacher due to excelling in math and writing. Her role as a tutor to her peers paid a stipend of $100 each year (Episcopal Archives).

In 1877, Cooper married George A.C. Cooper at the age of 19. George was a minister and taught Greek at St. Augustine. He passed away two years following their union. After this loss, Cooper did not remarry. She stayed at Saint Augustine Normal School beyond graduating, serving students as a matron by arranging domestic and medical care (Episcopal Archives).

Cooper remained staunchly committed to getting an education, and in 1881 enrolled at Oberlin College in Ohio. Her achievements at St. Augustine permitted her to skip freshman year and entered college as a sophomore (Episcopal Archives). Cooper quickly found that she had to advocate for the same educational offerings for women as she once did at Saint Augustine (National Museum of African American History and Culture). Fortunately, she was triumphant and accepted into the same courses as her male peers. She graduated with her bachelor's degree in 1884 and received her master's in 1887 – both in Mathematics (Douglass Day). Shortly after graduating, she transitioned from student to educator, and took on a position as a math and science teacher at Washington High School (later M Street High School, and presently Dunbar High School) in Washington, DC.

Fostering a Love of Education

Just five years after starting at Washington High School, Cooper transitioned to the role of principal. Her philosophies differed greatly from those of her peers. Many adopted the views of Booker T. Washington, who “urged blacks to subordinate demands for political and equal rights, and concentrate instead on improving job skills and usefulness through manual labor,” (National Museum of African American History and Culture). Cooper, however, felt that students should seek collegiate level education and be granted the tools and resources to successfully do so. She set out to enhance vocational programs while also implementing college preparatory programs.

As principal, she recognized that students had a variety of circumstances, such as “[coming] from poor families, [growing] up with little previous access to education, [or] might [needing] more time for tests or a longer deadline for schoolwork,” (Bates 2015). The support she provided included aiding students in earning scholarships and matching them to universities. This proved to be extremely successful, with some students ultimately attending Yale, Mount Holyoke, Brown and Harvard.

However, despite the success of Cooper’s vision, school administrators instructed her to return to Booker T. Washington’s ideologies and forgo her emphasis on college. She refused and promptly resigned. Cooper’s next role was at the Lincoln Institute located in Jefferson, Missouri. While in Missouri, Cooper sought to return to Washington High School. Cooper was rehired in 1910, though this time as a Latin teacher instead of as principal.

Though undoubtedly invested in the academic journeys of her students, Cooper also continued to invest in her own journey as a learner. In the summers of 1911 and 1913, she attended the Guilde Internationale de Paris. There she studied French history, literature, and linguistics. In 1914, she set her sights on working towards a PhD and was accepted into Columbia University as a doctoral student. The following year, after her brother’s passing, she adopted his five children. This undoubtedly kept Cooper busy, so much so that she was unable to fulfill all of Columbia’s requirements. She remained staunchly committed to teaching and to her adopted children.

Eventually, in 1924, Cooper transferred to Paris’ Sorbonne University in 1924. Her dissertation was written in French and explored attitudes about enslavement post-Haitian rebellion (Bates 2015). Cooper received her doctorate at 65. This made her the fourth African American woman in the United States to earn a PhD (Bates 2015). All the while, she remained a teacher. Cooper did not retire from Washington High School until 1930 - she was 72. Though her time as a traditional educator had ended, she remained active within the many conversations surrounding African American freedom and education.

A Voice from the South: A Black Feminist Staple

Though teaching was often at the forefront of her mind, Cooper had extensive philosophies on a variety of pressing social topics. As such, while working as a teacher, she published a book entitled A Voice from the South: By a Black Woman in the South in 1892. This piece was one factor that made Cooper a voice of authority on issues of education and activism. While her book explored Jim Crow Laws and stereotypes about African Americans, the text was most widely celebrated for Cooper’s proposed necessity for racial uplift: affording Black women the opportunity to get an education. She felt that Black women had a unique understanding of the world due to factors of both race and gender (Carey). In fact, by exploring barriers to access such as sexism and racism, this text is also said to be the first “book length articulation of Black feminist theory,” (Carey). Furthermore, Cooper’s opening statement in the text set the tone for the rest of the work. She remarked,

“I speak for the colored women of the South, because it is there that the millions of Blacks in this country have watered the soil with blood and tears, and it is there that the colored woman of America has made her characteristic history and there her destiny is evolving,” (Cooper 1892).

The musings within this text are considered some of the earliest articulations of intersectionality. Intersectionality is understood as “the process of understanding how the complex intersection between gender, race, and class impacts individuals,” (Carey). She emphasized how identity often renders Black women invisible in many settings (i.e. women’s suffrage), highlighting the tools necessary to prop them up. Additionally, she also discussed issues of class and labor in relation to race - solidifying her spot in a conversation often dominated by Black men such as W.E.B. Du Bois (with whom Cooper was friends) and Booker T. Washington. Cooper did not only work for her and her alone to be heard, but other Black girls and women as well. Within A Voice from the South she wrote:

““[G]ive the girls a chance!...Let our girls feel that we expect more from them than that they merely look pretty and appear well in society. Teach them that there is a race with special needs which they and only they can help; that the world needs and is already asking for their trained, efficient forces,” (Cooper 1892).

A Voice from the South gave Cooper opportunities to lecture on social justice at various locations throughout the nation. She expanded upon her ideas regarding Black women, activism, education and civil rights (Columbia University). Cooper spoke at conferences such as the World's Congress of Representative Women at the Chicago World's Fair in 1893, the Woman Suffrage Congress in 1893, and the Pan-African Conference in London in 1900 (Episcopal Archives). Though A Voice from the South was one of her most celebrated works, Cooper wrote a variety of poems (many of which were unpublished), plays and articles (National Museum of African American History and Culture).

Additionally, amid various speaking engagements, she also co-founded and was involved in a variety of organizations. These included founding the Colored Women’s League, serving on the executive committee of the first Pan-African Conference, being the first woman member of the American Negro Academy, and developing branches of the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) and the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) specifically for African American members (Columbia University). She dubbed the latter organization the Phyllis Wheatley Young Women’s Christian Association (National Museum of African American History and Culture).

Later Life and Legacy

Cooper’s career as both an educator and activist persisted well into old age. At 72, Cooper became the president of Frelinghuysen University. Frelinghuysen offered Black adults both vocational and academic experiences. The university embodied much of Cooper’s own personal philosophies, which resulted in her continuous support - so much so that, once she completed her presidency, she then served as registrar for ten additional years until its closing in 1950 (Episcopal Archives). Cooper continued to advocate for quality education until her passing. She passed away on February 27th, 1964 at the age of 105 and was buried next to her husband.

Anna Julia Cooper’s work remains a guiding light for many. She advocated for better educational opportunities for her own community, all while shedding light onto the realities of the experiences of Black women. Her work has been celebrated in many forms, such as within the U.S. passport where her quote - "The cause of freedom is not the cause of a race or a sect, a party or a class – it is the cause of humankind, the very birthright of humanity." - is highlighted – the only quote included in the U.S. passport from any woman. Cooper has also been honored on a U.S. Postal Service commemorative stamp, and both a middle school and center at a university named in her honor. Though her legacy shows up in several ways socially and culturally, one thing remains true: Cooper laid the foundation upon which many African American women stand on today, both students and educators alike.

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

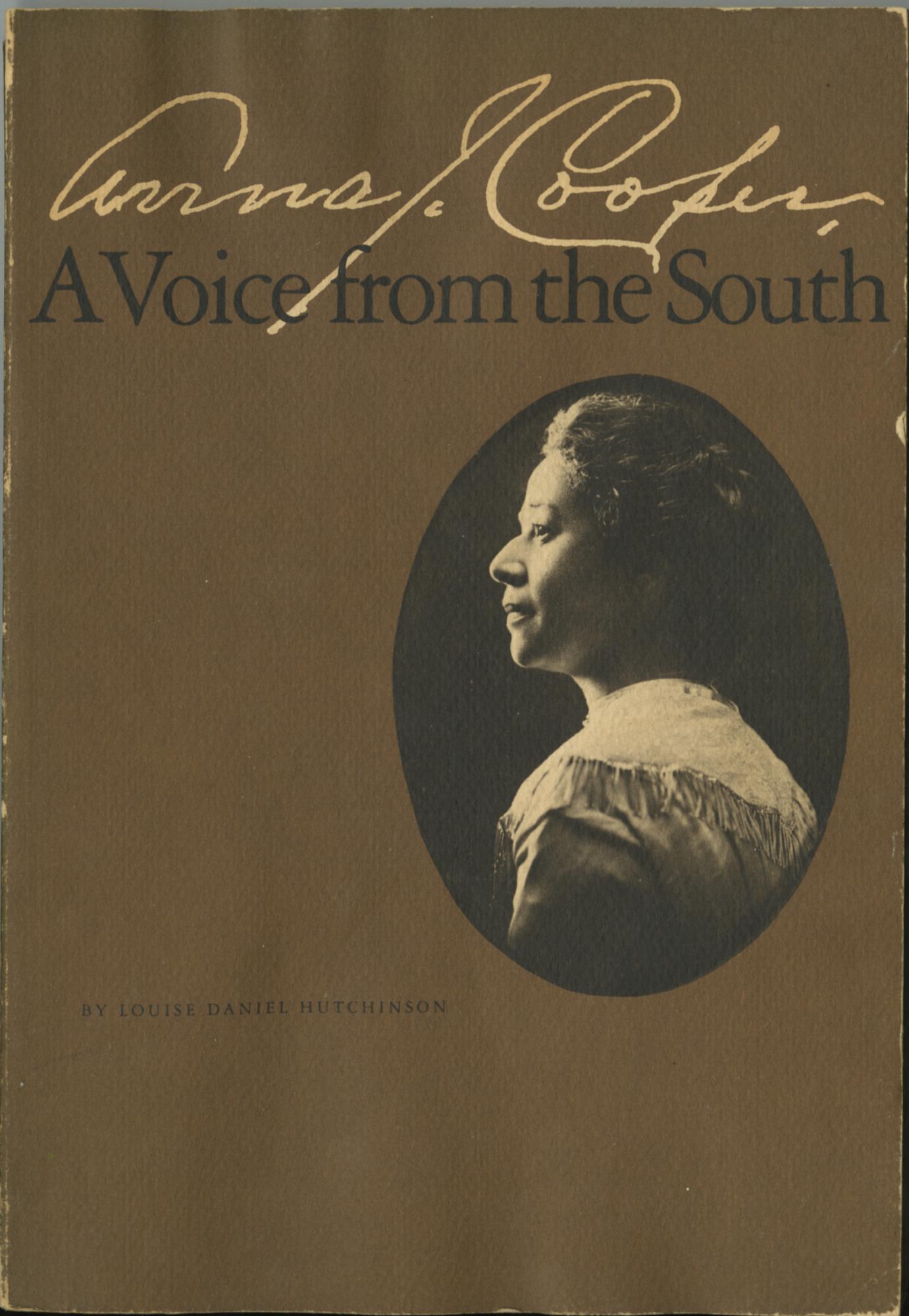

A Voice from the South book cover (Photograph)

Caption: The cover of Cooper’s text, A Voice from the South. A portrait of her can be seen just below the title.

Primary Source Analysis Questions:

-

Who do you believe was the target audience for this book? What aided you incoming to this conclusion?

-

What can you learn about the text from examining the cover?

Cooper pictured at Frelinghuysen University (Photograph)

Caption: Anna Julia Cooper stands in the Frelinghuysen University Registrar's office circa 1930.

Primary Source Analysis Questions:

-

What details stand out to you in this image?

-

What do you wonder about the setting this image was taken in?

Educator Notes

This resource outlines different lenses that students can examine through primary resources. There is no specific order to use the columns in. The questions students develop through their examination are meant to encourage further research and curiosity. Educators can then propose other activities (as outlined in the resource) that help students further contextualize different - but related - primary sources.

This is a blank version of the previous link. Educators can create their own specific sample questions (most likely based on the medium of the primary source to have students answer in each column), or simply have students fill out this document with the guidance of the original document.

“Anna Julia Cooper | Columbia Celebrates Black History and Culture.” Columbia University. https://blackhistory.news.columbia.edu/people/anna-julia-cooper.

“Anna Julia Cooper: Educator, Writer and Intellectual.” National Museum of African American History and Culture. n.d. https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/anna-julia-cooper-educator-writer-and-intellectual.

Bates, Karen Grigsby. “A Child of Slavery Who Taught a Generation.” NPR, March 12, 2015. https://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2015/03/12/385176497/a-child-of-slavery-who-taught-a-generation.

“Biography of Anna Julia Cooper.” Douglass Day. https://douglassday.org/cooper/.

Carey, Mia. “Dr. Anna Julia Cooper (1859-1964) (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service. https://www.nps.gov/people/dr-anna-julia-cooper-1859-1964.htm.

“The Church Awakens: African Americans the Struggle for Justice Anna Julia Haywood Cooper, 1858-1964.” The Episocopal Archives. n.d. https://episcopalarchives.org/church-awakens/exhibits/show/leadership/lay/cooper.

Cooper, Anna J. A Voice from the South. New York :Oxford University Press, 1988. https://docsouth.unc.edu/church/cooper/cooper.html.

“Booker T. Washington and the ‘Atlanta Compromise.’” National Museum of African American History and Culture. https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/booker-t-washington-and-atlanta-compromise.

“Freedmen’s Bureau Acts of 1865 and 1866.” U.S. Senate: Freedmen’s Bureau Acts of 1865 and 1866, August 8, 2023. https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/FreedmensBureau.htm.

Washington, Mary Helen. “Anna Julia Cooper: The Black Feminist Voice of the 1890s.” Legacy (1987): 3-15. (via JSTOR)

Main image citation: Anna J. Cooper letter to Anna M. Jackson. Branson-Jackson Family Papers, SFHL-RG5-016, Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College. A00183425. http://inherownright.org/records/oai-digitalcollections-tricolib-brynmawr-edu-sc_183689.

MLA – Dawson, Shay. "Anna Julia Cooper." National Women's History Museum. National Women's History Museum, 2024. Date accessed.

Chicago - Dawson, Shay. “Anna Julia Cooper." National Women's History Museum. 2024.

May, Vivian M. Anna Julia Cooper, Visionary Black Feminist: A Critical Introduction. New York: Routledge, 2007.

Moody-Turner, Shirley. The Portable Anna Julia Cooper. New York: Penguin Books, 2022.