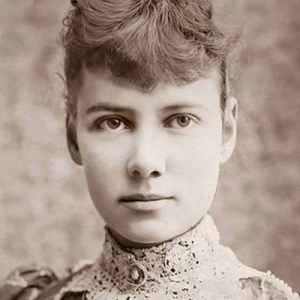

Nellie Bly

Nellie Bly became a star journalist by going undercover as a patient at a New York City mental health asylum in 1887 and exposing its terrible conditions in the New York World. Her reporting not only raised awareness about mental health treatment and led to improvements in institutional conditions, it also ushered in an age of investigative journalism. Her illustrious career also included a headline-making journey around the world, running an oil manufacturing firm, and reporting on World War I from Europe.

Nellie Bly was born Elizabeth Jane Cochran on May 5, 1864 in Cochran’s Mill, Pennsylvania. Her father, Michael Cochran, owned a lucrative mill and served as associate justice of Armstrong County. When Bly was six, her father died suddenly and without a will. Unable to maintain the land or their house, Bly’s family left Cochran's Mill. Her mother remarried but divorced in 1878 due to abuse. At 15, Bly enrolled at the State Normal School in Indiana, Pennsylvania. It was there that she added an “e” to her last name, becoming Elizabeth Jane Cochrane. Due to the family’s financial struggles, she left the school after one term and soon moved with her mother to Pittsburgh, where her two older brothers had settled.

Bly looked for work to help support her family, but found fewer opportunities than her less-educated brothers. In response to an article in the Pittsburg[h] Dispatch that criticized the presence of women in the workforce, Bly penned an open letter to the editor that called for more opportunities for women, especially those responsible for the financial wellbeing of their families. The newspaper’s editor, George Madden, saw potential in her piece and invited her to work for the Dispatch as a reporter. She used the pen name Nellie Bly, which she took from a well-known song at the time, “Nelly Bly.” Bly was a popular columnist, but she was limited to writing pieces that only addressed women and soon quit in dissatisfaction.

Wanting to write pieces that addressed both men and women, Bly began looking for a newspaper that would allow her to write on more serious topics. She moved to New York City in 1886, but found it extremely difficult to find work as a female reporter in the male-dominated field. In 1887, Bly stormed into the office of the New York World, one of the leading newspapers in the country. She wanted to write a story on the immigrant experience in the United States. The editor, Joseph Pulitzer, declined that story, but he challenged Bly to investigate one of New York’s most notorious mental asylums, Blackwell’s Island. Bly not only accepted the challenge, she decided to feign mental illness to gain admission and expose firsthand how patients were treated. With her courageous and bold act, she cemented her legacy as one of the most notable journalists in history.

Bly’s six-part series on her experience in the asylum was called Ten Days in the Madhouse and quickly made Bly one of the most famous journalists in the country. Her reporting on life in the asylum shocked the public and led to increased funding to improve conditions in the institution. Furthermore, her hands-on approach to reporting developed into a practice now called investigative journalism. Bly continued to produce regular exposés on New York’s ills, such as corruption in the state legislature, unscrupulous employment agencies for domestic workers, and the black market for buying infants. Her straightforward yet compassionate approach to these issues captivated audiences.

Bly’s successful career reached new heights in 1889 when she decided to travel around the world after reading the popular book by Jules Verne, Around the World in 80 Days. The New York World published daily updates on her journey and the entire country followed her story. Her trip only took 72 days, which set a world record. But Bly held the record for only a few months before it was broken by businessman George Francis Train who completed the journey in 67 days.

Bly continued to publish influential pieces of journalism, including interviews with prominent individuals like anarchist activist and writer Emma Goldman and socialist politician and labor organizer Eugene V. Debs. She also covered major stories like the march of Jacob Coxey’s Army on Washington, D.C. and the Pullman strike in Chicago, both of which were 1894 protests in favor of workers’ rights.

At the age of 30, Bly married millionaire Robert Seamen and retired from journalism. Bly’s husband died in 1903, leaving her in control of the massive Iron Clad Manufacturing Company and American Steel Barrel Company. In business, her curiosity and independent spirit flourished. Bly went on to patent several inventions related to oil manufacturing, many of which are still used today. She also prioritized the welfare of the employees, providing health care benefits and recreational facilities. Unfortunately, Bly did not manage the finances well and fell victim to fraud by employees that led the firm to declare bankruptcy.

In her later years, Bly returned to journalism, covering World War I from Europe and continuing to shed light on major issues that impacted women. While still working as a writer, Bly died from pneumonia on January 27, 1922. In a tribute after her death, the acclaimed newspaper editor Arthur Brisbane remembered Bly as “the best reporter in America.”

Kroeger, Brooke. "Bly, Nellie (1864-1922), reporter and manufacturer." American National Biography. Feb. 1, 2000; Accessed April 27, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1601472

Lutes, Jean Marie. “Into the Madhouse with Nellie Bly: Girl Stunt Reporting in the Late Nineteenth Century America.” American Quarterly, 54 no 2. (June 2002) 217-253.

“Nellie Bly” PBS: American Experience, Accessed 23 March 23, 2017 http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/world/peopleevents/pande01.html

“Life Story: Elizabeth Cochrane, aka Nellie Bly (1864-1922),” Women & The American Story, New-York Historical Society Library and Museum, https://wams.nyhistory.org/modernizing-america/modern-womanhood/nellie-bly/

MLA – Norwood, Arlisha and Mariana Brandman. "Nellie Bly." National Women's History Museum. National Women's History Museum, 2022. Date accessed.

Chicago- Norwood, Arlisha and Mariana Brandman. "Nellie Bly." National Women's History Museum. 2022. www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/nellie-bly.

Image Credit: Library of Congress

Bernard, Karen. “She went undercover to expose an insane asylum’s horrors. Now Nellie Bly is getting her due.” The Washington Post. July 28, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2019/07/28/she-went-undercover-expose-an-insane-asylums-horrors-now-nellie-bly-is-getting-her-due/

Bly, Nellie. Ten Days in the Madhouse. New York, Nellie Bly Press, 2017.

Goodman, Matthew. Eighty Days: Nellie Bly and Elizabeth Bisland's History-Making Race Around the World.

Kroeger, Brooke. Nellie Bly: Daredevil, Reporter, Feminist. New York: Crown, 1994.

Pace, Lawson. “Nellie Bly: Around the World in 72 Days.” Senator John Heinz History Center. https://www.heinzhistorycenter.org/learn/women-forging-way/nellie-bly-around-the-world

“Ten Days in the Madhouse.” A Celebration of Women Writers. http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/bly/madhouse/madhouse.html

The evening world. (New York, N.Y.), 14 Nov. 1889. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030193/1889-11-14/ed-3/seq-1/