Ruby Bridges

Ruby Bridges has always been a civil rights advocate, with her experience as the first Black child to enter an all-white school in the South making her a household name.

Though her experience in school was harrowing due to blatant racism and the targeting of her family, Bridges never missed a day of school.

Presently, the Ruby Bridges Foundation and Bridges herself continue to host speaking engagements and write children’s books to strive for an end to racism in America.

“All of us are standing on someone else’s shoulders. Someone else that opened the door and paved the way. And so, we have to understand that we cannot give up the fight, whether we see the fruits of our labor or not. You have a responsibility to open the door to keep this moving forward.”

Ruby Bridges, The Guardian, 2021

Early Life

Ruby Bridges was born on September 8, 1954, to Abon and Lucille Bridges, who had married the previous year and lived in Tylertown, Mississippi. Abon worked as a mechanic and was a veteran of the Korean War, while Lucille was employed in domestic work (Rose, 2021). In her early childhood, the Bridges family relocated to New Orleans, Louisiana, seeking better job opportunities and higher-quality education for their children (Smith, 2021). Their move coincided with a pivotal moment in American education as 1954 was the same year the U.S. Supreme Court issued its landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, which declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional. The Supreme Court ruled that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” (Library of Congress 2004). This decision required all schools to desegregate, providing Black students with the opportunity to attend what were once all-white institutions. Segregation, both by law and by custom, started soon after the abolition of slavery in the 19th century. Though various amendments to the Constitution had been passed to provide African Americans with rights to citizenship and the right to vote, other legal decisions were made that worked to nullify these amendments. Both socially and politically, African Americans were “relegated to the status of second-class citizens” (Pilgrim, 2000). They were separated from their white counterparts not only by law but by “private action in transportation, public accommodations, recreational facilities, prisons, armed forces, and schools in both Northern and Southern states” (Library of Congress 2004).

Furthermore, the Library of Congress expands on this, stating: “In 1896, the Supreme Court sanctioned the legal separation of the races by its ruling in H.A. Plessy v. J.H. Ferguson, which held that separate but equal facilities did not violate the U.S. Constitution's Fourteenth Amendment,” (Library of Congress 2004). The Brown v. Board ruling in 1954 overturned these separations in the realm of education. Even with this ruling, Louisiana struggled to enact integration. It was not until November 14, 1960, that Louisiana schools began to desegregate due to an official order by Federal Judge Skelly Wright (Norman Rockwell Museum n.d.). Schools could refuse, though Judge Wright made it clear: “They could opt to close if they refused to integrate,” (Devlin 2020). Bridges’ opportunity to attend William Frantz Elementary School as a first grader came at the request of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The NAACP worked tirelessly to eliminate the legal obstacles that upheld public-school segregation (Library of Congress 2004).

They became aware of Ruby when they discovered that she was one of six children who passed the required entrance exams. These exams aimed to see which African American students could succeed within all-white institutions. Bridges’ father was said to be reluctant, but her mother was eager for her daughter to have this opportunity. Lucille’s mother and father did not have the opportunity to receive an education, and she had to leave school in the eighth grade to assist her parents in the fields (Smith 2021). This prompted her to encourage Ruby to pursue an education, no matter the many trials that lay ahead. With this decision, Bridges became a trailblazer at just the age of six as the first African American child in the South to attend an all-white elementary school.

The Impact of Integration

On Bridges’ first day at William Frantz Elementary, she had to be accompanied by U.S. Marshals. Protests from white parents and officials led to concerns for her safety. In fact, “...White parents in Louisiana vehemently protested the idea, and school boards and politicians sought to block desegregation in the state,” (Devlin 2020). Once let into the school, Bridges was brought to the principal’s office immediately. She recalls that, “...The crowd that was outside, they immediately rushed in behind me. They started to run into every class, and they took every child out of school. So, by the end of that day, 500 kids… were taken out,” (Bridges 2024). She mused that her entire first day was spent in the principal’s office.

Upon attending the once all-white school for the first time, Bridges not only faced blatant discrimination but was also the only student in her class. Her teacher, Barbara Henry, was a white woman from Boston. She solely taught Bridges for the entirety of first grade. Many years later, Bridges’ spoke highly of Henry and remarked that “Even though she looked exactly like people outside the school, she showed me her heart,” (Bridges 2015). Despite these circumstances, Bridges never once missed a day of school. She was escorted each day by both her mother and U.S. Marshals (Smith 2021).

The racism she faced each day while attending school took on various forms: many white students’ parents chose to homeschool them, objects were thrown at her, and, perhaps most harrowing, Bridges recalls being “greeted” by a woman displaying a black doll in a wooden coffin (Hilbert College n.d.). Additionally, Bridges could not partake in communal spaces such as the cafeteria (she brought her own lunch for fear of being poisoned) or the playground (she often played inside with her teacher), and when she needed to use the bathroom, she was accompanied by a U.S. Marshall (Rose, 2021; Hilbert College n.d.). Though courageous, the choice to allow Bridges to attend an all-white school also impacted her family. Disdain for Bridges’ presence at William Frantz Elementary caused Lucille to lose her job (Rose 2021). Abon also lost his job, though he was encouraged by the NAACP to refrain from looking for work as it might put him in danger (Rose 2021). This created tension within the home, though even Bridges’ grandparents - who did not live with the family - were impacted negatively all the way in Mississippi. Bridges stated, “I’m the oldest of eight, and at that point he was no longer able to provide for his family. So they were solely dependent on donations and people that would help them” (Bridges 2021).

Her parents would eventually split because of their circumstances. Having recognized that a young Bridges had faced a series of difficult life events in an unbelievably short period of time, child psychiatrist Robert Coles volunteered his services to her. Though white, he aimed to support Bridges and her family. He conducted weekly visits. His career flourished, with Coles eventually pursuing a career in studying how desegregation impacted young children (Rose 2021). While circumstances often felt dire for Bridges, white parents started to change their minds. White parents began to allow their children to attend William Frantz, though Bridges did not know this at first. The principal of the school had still been separating the white students from her. Barbara Henry advocated for Bridges’ inclusion with other students, pleading, “The law's changed and kids can be together now, but you're hiding them from Ruby. If you don't allow them to come together, I'm going to report you to the superintendent,” (Kelly, et. al. 2022). The principal yielded at the end of the school year, allowing the students to intermingle. Though exciting, Bridges’ hopes were soon dashed. A young boy asserted that he was not allowed to play with her, calling her a racial slur. Bridges reflected that:“...the minute he said that, it was like everything came together. All the little pieces that I’d been collecting in my mind all fit, and I then understood: the reason why there’s no kids here is because of me, and the color of my skin. That’s why I can’t go to recess. …It all sort of came together: a very rude awakening. I often say today that really was my first introduction to racism,” (Bridges 2021). Though she asserts that the boy was simply explaining why they could not be friends, it was an eye-opening experience that laid the foundation for the work Bridges would do later in life.

During Bridges’ second year in attendance, circumstances changed. She was able to be in class with other students, she was no longer the only African American within the class (with the number increasing year by year), and she was no longer greeted by protests each day. Barbara Henry eventually left that school, though she and Bridges would remain in touch. Bridges would go on to high school, which, by the time of her attendance, had been desegregated for just under a decade (Rose 2021). Though not picture-perfect, as tensions remained between Black and white students, her later educational experiences looked quite different from that of her time as a first grader.

Art, Adulthood, and Advocacy

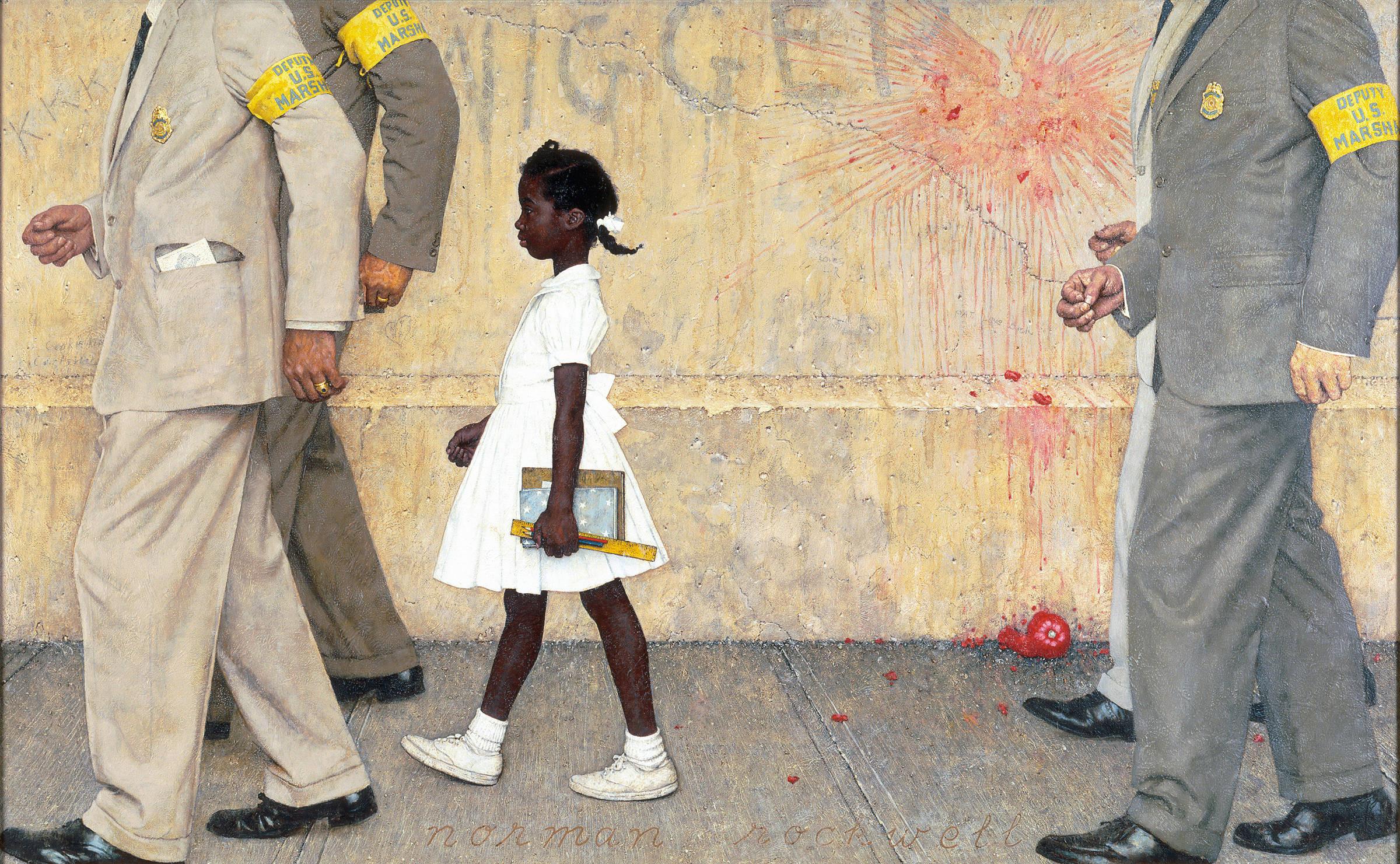

Though Bridges’ first steps into William Frantz have been documented in photos, film, and even adapted for film, one iconic work of art also tells Ruby’s tale. The Problem We All Live With was created by artist Norman Rockwell in 1963, just three years after Bridges made history. Rockwell’s painting depicts her being escorted into the school and, most notably, has been framed at her height so that the viewer can see things from her perspective (Pastan 2022). This work was met with both praise and heavy criticism. The painting was featured in “LOOK” magazine, with some readers celebrating Rockwell’s courageousness and others condemning it (Norman Rockwell Museum n.d.). As an adult, Bridges has appreciated The Problem We All Live With and Rockwell’s decision to highlight her story: “Here was a man that had been doing lots of work, painting family images, and all of a sudden decided this is what I’m going to do…he had enough courage to step up to the plate and say I’m going to make a statement, and he did it in a very powerful way…”(Pastan 2022). Rockwell went on to create other paintings highlighting racial tensions. The Problem We All Live With ushered in a new, socially conscious era for the artist just as desegregation ushered in a new era for America. Once Bridges graduated from high school, she set her sights on leaving Louisiana. She became a travel agent for American Express.

This role brought her the opportunity to travel the world for the next fifteen years of her life. She left her job as a travel agent in her mid-30s, seeking more fulfilling endeavors. Along the way, Bridges married Malcolm Hall in 1984, and the couple had four sons. Her brother was murdered in New Orleans in 1993, which also brought his four daughters into her and her husband’s care. In 1995, Robert Coles wrote a children’s book entitled “The Story of Ruby Bridges.” Though her story was remarkable, not many recognized her for it in her day-to-day life. Coles’ book put Bridges back in the mainstream conversation. She supported Coles in promoting his book. Disney then made a biopic entitled Ruby Bridges that came out in 1998. She served as a consultant on the film. Coles provided Bridges with proceeds from the success of the book, which granted her enough funds to develop her own foundation in 1999. The Ruby Bridges Foundation stands for the “values, tolerance, respect, and appreciation of all differences,” (Pastan 2022). Bridges also published various books, including This Is Your Time, Through My Eyes, and Dear Ruby, Hear Our Hearts. With her nieces still in her care, Bridges remained tied to William Frantz Elementary as the girls attended the same school as their change-making aunt. Upon noticing that the school lacked after-school arts programming, Bridges set out to make it happen.

Then, in 2005, Hurricane Katrina caused significant damage to the school, so much so that the local government intended to demolish it. Bridges stepped in—proclaiming that “I felt like if anybody was to save the school, it would be me”—and got the school placed on the National Register of Historic Places, which guaranteed its preservation (Bridges 2021). The school has since been restored and remains in operation. To show their thanks, a statue of Bridges is on display in the school’s courtyard.

Life and Legacy

Ruby Bridges’ courage cannot be understated. Her impact has far surpassed her first steps into William Frantz Elementary School in November of 1960. She has remained a vocal advocate for anti-racism and encourages kids to make meaningful connections with peers of all races. She has upheld the legacy of her parents, Abon and Lucille Bridges, her first-grade teacher, Barbara Henry, and child psychiatrist, Robert Coles, all of which sought to provide her with a solid foundation to enact change. She continues to pave the way for generations to come through her various advocacy efforts. Bridges’ contributions—both past and present—have been recognized far and wide. She holds various honorary degrees from Connecticut College in 1995 and Tulane University in 2012. In 2000, she was made an honorary Deputy U.S. Marshal. 10 years later, Bridges was honored at the White House. As of 2024, she was also inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame.

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Caption: An image of Ruby Bridges being escorted into William Frantz Elementary School by U.S. Marshals in November of 1960.

Analysis Questions:

-

Who do you think took this image? What clues in this photograph lead you to that conclusion?

-

What do you wonder about the men who are escorting Bridges in this image?

-

What does this image make you think about your own experience?

-

What bigger stories can you connect to what you see in this image? From the time it was taken? From today?

Caption: Norman Rockwell’s The Problem We All Live With depicts Bridges’ historic walk into William Frantz Elementary School. The scene is depicted at her height to highlight this experience from her perspective; slurs and tomatoes can be seen in the painting’s backdrop to highlight the discrimination she experienced at a young age.

Analysis Questions:

-

Examine the painting closely. What details are you drawn to?

-

Why do you think that this painting is historically important? Not only in the context of Rockwell’s other works, but in the context of the U.S. Civil Rights movement?

-

Who do you believe was the intended audience of this piece?

Caption: Ruby Bridges discusses her experience being the first Black student in the South to attend a once all-white institution. She also discusses her current reflections on that experience, particularly through the lens of her new book, Dear Ruby.

Analysis Questions:

-

Why do you think videos of Ruby Bridges discussing this historical event are important?

-

What did you hear in her recounting of events that surprised you?

Educator Notes

This resource outlines different lenses that students can examine through primary resources. There is no specific order to use the columns in. The questions students develop through their examination are meant to encourage further research and curiosity. Educators can then propose other activities (as outlined in the resource) that help students further contextualize different—but related—primary sources.

This is a blank version of the previous link. Educators can create their own specific sample questions (most likely based on the medium of the primary source to have students answer in each column), or simply have students fill out this document with the guidance of the original document.

“Brown v. Board at Fifty: ‘With An Even Hand’ Exhibition Items.” Library of Congress, November 13, 2004. https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/brown/brown-overview.html.

“Civil Rights Pioneer on First-Grade Teacher: ‘She Showed Me Her Heart’ | Where Are They Now | Own.” YouTube, January 1, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qwb5xsRO1yc&t=2s.

Devlin, Teresa. “Amid Hate and Division, Christmas Cards Flowed to the Girls Who Desegregated New Orleans Schools .” The Historic New Orleans Collection, December 22, 2020. https://www.hnoc.org/publications/first-draft/amid-hate-and-division-christmas-cards-flowed-girls-who-desegregated-new.

Kelly, Mary Louise, Elena Burnett, Mallory Yu, and Courtney Dorning. “Ruby Was the First Black Child to Desegregate Her School. This Is What She Learned.” NPR, September 7, 2022. https://www.npr.org/2022/09/07/1121133099/school-segregation-ruby-bridges.

Pastan, Amy. “Norman Rockwell + the Problem We All Live With.” The Kennedy Center, January 22, 2022. https://www.kennedy-center.org/education/resources-for-educators/classroom-resources/media-and-interactives/media/visual-arts/norman-rockwell--the-problem-we-all-live-with/.

Pilgrim, David. “What Was Jim Crow.” Jim Crow Museum, 2000. https://jimcrowmuseum.ferris.edu/what.htm.

Rose, Steve. “Ruby Bridges: The Six-Year-Old Who Defied a Mob and Desegregated Her School.” The Guardian, May 6, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/may/06/ruby-bridges-the-six-year-old-who-defied-a-mob-and-desegregated-her-school.

“Ruby Bridges .” Ruby Bridges | Social Activist | Hilbert College. N.d. https://www.hilbert.edu/social-justice-activists/ruby-bridges.

“Ruby Bridges: Racism Is a Grown-up Disease. Let’s Stop Using Our Kids to Spread It.” YouTube, January 23, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GW7tbMF1Wto.

Smith, Johnessa. “Lucille Bridges: Hero of School Desegregation.” Georgia Commission on Women, May 12, 2021. https://www.gacommissiononwomen.org/lucille-bridges-hero-of-school-desegregation/.

“‘The Problem We All Live With’ - Norman Rockwell (1894-1978) - Google Arts & Culture.” Norman Rockwell Museum. N.d. https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/the-problem-we-all-live-with-norman-rockwell-1894-1978/qwGpXUCsX0RPAQ?hl=en.

Citation for primary image: Six-year-old Ruby Bridges, three-quarter length portrait, standing, facing front. , 1960. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/00651757/.

MLA – Dawson, Shay. "Ruby Bridges." National Women's History Museum. National Women's History Museum, 2024. Date accessed.

Chicago - Dawson, Shay. “Ruby Bridges." National Women's History Museum. 2024.

Bridges, Ruby and John Jay Cabuay. 2024. Dear Ruby, Hear Our Hearts. Scholastic Inc.

“‘What Protected Me Was the Innocence of a Child’: Ruby Bridges Reflects on 1960 School Integration.” YouTube, April 28, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-A4pqfkK3vI.

This biography is sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University. Content created and featured in partnership with the TPS program does not indicate an endorsement by the Library of Congress.

For further information or questions, please contact history@womenshistory.org.