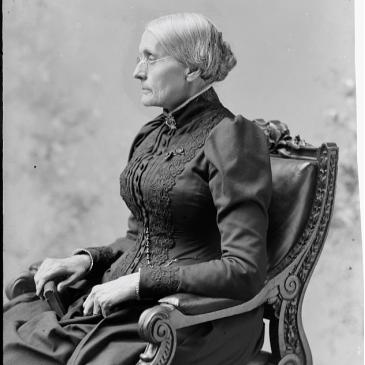

Matilda Joslyn Gage

Famously referred to as “the woman who was ahead of the women who were ahead of their time,” author, activist, and lecturer Matilda Joslyn Gage worked tirelessly to advocate for abolition, women’s rights, and Native American rights. While her opinions were considered extremely radical for her time, Gage paved the way for the women’s movement and social progress in the United States.

Gage was born on March 24, 1826 in Cicero, New York. Gage’s beliefs were heavily influenced by her parents. Her mother, Helen Leslie Joslyn, had a passion for historical research and her father, Dr. Hezekiah Joslyn, was an abolitionist who made their family home into a station on the Underground Railroad. As a child, Gage handed out abolitionist pamphlets and admired powerful anti-slavery speakers like Fredrick Douglass. In addition to her public school education, Gage received lessons in anatomy and physiology from her father to prepare her for medical school. However, after she went to Clinton Liberal Institute, a coeducational preparatory school, she was refused admission to medical school because she was a woman.

She married Henry Gage, a dry goods merchant, in 1845. The couple settled in Fayetteville, New York and they had five children. Even though Gage faced the potential for harsh penalties and jail, she opened her home to those fleeing slavery. Gage began writing for newspapers in the 1850s and continued to do so throughout her career. Her advocacy for women’s rights began with her speech at the third National Women’s Convention in Syracuse in 1852. As the Civil War began, Gage supported Union soldiers from New York by hosting events to raise money for military hospitals. In 1869, she helped found the New York State Woman Suffrage Association and served as president for nine years. She held many executive positions in the association and never sat on the sidelines when there was work to be done.

Gage continued her work advocating for women’s rights. In 1870, she wrote “Woman as Inventor,” in which she credited Catherine Littlefield Greene with the invention of the cotton gin. She supported women's rights to divorce and reproductive autonomy while serving as president of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) from 1875-1876. Gage was at the forefront of the women’s suffrage movement and collaborated closely with other activists like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Gage was the one suffragist who backed Anthony when she was put on trial for voting in the 1872 presidential election. Gage, Stanton, and Anthony compiled the first three volumes of a six-volume series called History of Woman Suffrage. Gage also wrote for the NWSA newspapers as well as her own paper from 1878 to 1881.

Although Gage had many ambitions for NWSA, others like Anthony wanted to focus solely on getting the vote and gaining the support of other conservative organizations within the women’s suffrage movement. Gage had certain opinions that differed with those of the conservative women’s groups, such as her belief that the church was patriarchal. These differences prompted her to form the Woman’s National Liberal Union (WNLU) in 1890. She spent the remaining years of her life advocating for social reforms, writing for the WNLU journal called The Liberal Thinker, and making public speeches. For example, at the unveiling of the Statue of Liberty in 1886, Gage spoke out in protest about the hypocrisy of “liberty for all” when women did not have basic liberties. In 1893, Gage published Women, Church, and State, which called out what she felt was the patriarchy and misogyny within the church’s teachings. In it, she praised Presbyterians for ordaining female deacons, exposed the sexual abuse of children and women by priests, and decried sex trafficking in the United States. In the book, she also highlighted groups of Native Americans that served as examples of societies that treated women and men equally. Gage, along with twenty-four other women, composed The Woman’s Bible in 1895, which featured Bible verses about women accompanied by analysis from the contributors.

On many occasions, Gage publicly criticized the treatment of Native Americans by the federal government. Gage highlighted the poor treatment of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) and other native nations in the New York Evening Post and in her speeches. Her advocacy and genuine desire for life to improve for Native Americans led Gage to be honorarily adopted into the Wolf Clan of the Mohawk Nation in 1893. They gave her the name Karonienhawi, meaning “she who holds the sky.”

Gage continued her work advocating for oppressed groups for as long as she could. She passed away on March 18, 1898 from a stroke. Her dozens of publications, speeches, and her activism carved a path for future radical feminists. In the 1990s, scientist Margaret Rossiter coined the term “Matilda effect” in honor of Gage. The term refers to when women scientists receive less or no credit for the work they do in the field. The term pays homage to Gage for using her voice to credit women for inventions for which men publicly received credit. Gage was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1995. Her work has invaluably influenced reform movements in the United States.

Boland, Sue. “The Power of Women: Matilda Joslyn Gage and the New York Women’s Vote of 1880.” New York History, Vol. 100, No. 1. 2019. Pgs. 28–50. Accessed 15 October 2021. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/734937/pdf

“Gage, Matilda Joslyn (1826-1898).” Civil War Era and Reconstruction (1861-1877). 2013. Pgs. 326–28. https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/lib/asulib-ebooks/reader.action?docID=2005320&ppg=291

Snodgrass, Mary Ellen. The Civil War Era and Reconstruction: An Encyclopedia of Social, Political, Cultural and Economic History. Taylor & Francis Group. 2011. Pgs. 268-269.

“Who Was Matilda Joslyn Gage?”. Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation. 2018. Accessed 14 October 2021. https://matildajoslyngage.org/about-gage

MLA- Angelucci, Ashley. “Matilda Joslyn Gage.” National Women’s History Museum. 2021. Date Accessed.

Chicago- Angelucci, Ashley. 2021. “Matilda Joslyn Gage.” National Women’s History Museum. www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/matilda-joslyn-gage.

Image Credit: Matilda Joslyn Gage photo posted by the National Women’s Hall of Fame. She was inducted in 1995 as “a significant position in history as a radical feminist thinker and historian whose writings shaped her times.” https://www.womenofthehall.org/inductee/matilda-joslyn-gage/

Brammer, Leila R. Excluded from Suffrage History: Matilda Joslyn Gage, Nineteenth-Century American Feminist. Greenwood Press, 2000.

Gage, Matilda Joslyn. Woman, Church and State: a Historical Account of the Status of Woman through the Christian Ages: With Reminiscences of Matriarchate: by Matilda Joslyn Gage. C. H. Kerr, 1893, 1893. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t9x061n96&view=1up&seq=8&skin=2021

Hampton, Hayes. “The Crack Between Nature Illusory and Nature Real” Matilda Joslyn Gage’s Visions of Feminist Spirit. Distributed by ERIC Clearinghouse, 1995

“Matilda’s Work”. The Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation. 2018. Accessed 16 October 2021. https://matildajoslyngage.org/matildas-writings?blogcategory=Matilda%27s+Writings

“The Online Books Page”. Ed. John Mark Ockerbloom. Accessed 16 October 2021. https://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/book/lookupname?key=Gage%2c%20Matilda%20Joslyn%2c%201826%2d1898

Wagner, Sally Roesch. Matilda Joslyn Gage: She Who Holds the Sky. Sky Carrier Press. 1999.

Susan B. Anthony

This biography is sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University. Content created and featured in partnership with the TPS program does not indicate an endorsement by the Library of Congress.

For further information or questions, please contact [email protected].