Daring Dames

Throughout the history of the United States, there are stories of women who pushed the boundaries; whether it be by putting their bodies on the line to write a good news article, risking their life for the thrill of flight, showing up to school despite death threats, or methodically organizing communities to ensure better living conditions for everyone. Women have worked hard and sacrificed much through the centuries to achieve their status in American society. Here are four Daring Dames who defied stereotypes to accomplish great things.

Nellie Bly (1864-1922)

In 1886, 22-year-old Nellie Bly (born Elizabeth Cochrane) moved to New York City from Pennsylvania. Bly had gotten her start as a journalist when she penned an open letter to the editor of the Pittsburgh Dispatch which pointed out the paper’s negative representation of women. The editor not only read Bly’s response, he printed her rebuttal, and offered Bly a job as columnist. As a newspaper writer, she took the pen name Nellie Bly. Although, Bly was a popular columnist she was often asked to write pieces that only addressed women.

Upon her move to New York City, Bly stormed into the office of the New York World, one of the leading newspapers in the country. She expressed interest in writing a story on the immigrant experience in the United States. Although, the editor declined her story he challenged Bly to investigate one of New York’s most notorious mental hospitals. Bly not only accepted the challenge, she decided to feign mental illness to gain admission and expose how patients were treated. With this courageous and bold act Bly cemented her legacy as one of the foremost female journalists in history. After pretending to be mentally ill for 10 days, the New York World published Bly’s articles about her time in the insane asylum on Blackwell’s Island in a six-part series. Ten Days in the Madhouse quickly made Bly one of the most famous journalists in the United States. Furthermore, her hands-on approach to stories developed into a practice now called investigative journalism. Bly’s successful career reached new heights when she decided to travel around the world after reading the popular book Around the World in 80 Days. Her trip only took 72 days, which was a world record. Bly would only hold it for a few months.

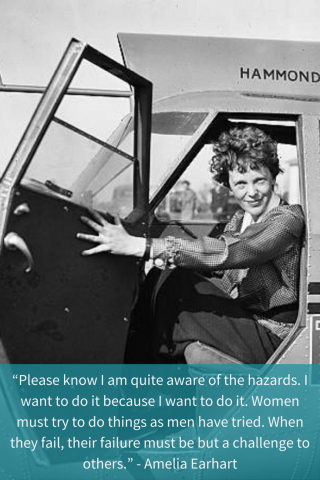

Amelia Earhart (1897-1937)

Amelia Earhart took her first plane ride in 1920. She quickly realized her true passion and began flying lessons with female aviator Neta Snook. On her twenty-fifth birthday, Earhart purchased a Kinner Airster biplane. She flew it, in 1922, when she set the women’s altitude record of 14,000 feet. With faltering family finances, she soon sold the plane. When her parents divorced in 1924, Earhart moved with her mother and sister to Massachusetts and became a settlement worker at Dennison House in Boston, while also flying in air shows.

Earhart’s life changed dramatically in 1928, when publisher George Putnam—seeking to expand on public enthusiasm for Charles Lindbergh’s transcontinental flight a year earlier—tapped Earhart to become the first woman to cross the Atlantic by plane. She succeeded, albeit, as a passenger. But when the flight from Newfoundland landed in Wales on June 17, 1928, Earhart became a media sensation and symbol of what women could achieve. Putnam remained her promoter, publishing her two books: 20 Hrs. 40 Mins. (1928) and The Fun of It (1932). Earhart married Putnam in 1931, though she retained her maiden name and considered the marriage an equal partnership.

In 1932, she became the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic—as a pilot. On June 1, 1937, she left Miami with navigator Fred Noonan, seeking to become the first woman to fly around the world. With 7,000 miles remaining, the plane lost radio contact near the Howland Islands. It was never found, despite an extensive search that continued for decades.

Dolores Huerta (1930-)

Dolores Huerta was greatly influenced by her mother’s community activism and compassionate treatment of workers. She also experienced extreme discrimination that helped shape her view of the world. A schoolteacher, prejudiced against Hispanics, accused Huerta of cheating because her papers were too well-written. In 1945 at the end of World War II, white men brutally beat her brother for wearing a Zoot-Suit, a popular Latino fashion. These experiences as a child led her to want to help others experiencing the same discrimination. Huerta briefly taught school in the 1950s, but seeing so many hungry farm children coming to school, she thought she could do more to help them by organizing farmers and farm workers.

In 1955 Huerta began her career as an activist when she co-founded the Stockton chapter of the Community Service Organization (CSO), which led voter registration drives and fought for economic improvements for Hispanics. She also founded the Agricultural Workers Association. Through a CSO associate, Huerta met activist César Chávez, with whom she shared an interest in organizing farm workers. In 1962, Huerta and Chávez founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), the predecessor of the United Farm Workers’ Union (UFW), which formed three year later. Huerta served as UFW vice president until 1999.

Despite ethnic and gender bias, Huerta helped organize the 1965 Delano strike of 5,000 grape workers and was the lead negotiator in the workers’ contract that followed. Throughout her work with the UFW, Huerta organized workers, negotiated contracts, advocated for safer working conditions including the elimination of harmful pesticides. She also fought for unemployment and healthcare benefits for agricultural workers. Huerta was the driving force behind the nationwide table grape boycotts in the late 1960s that led to a successful union contract by 1970.

In 1973, Huerta led another consumer boycott of grapes that resulted in the ground-breaking California Agricultural Labor Relations Act of 1975, which allowed farm workers to form unions and bargain for better wages and conditions. Throughout the 1970s and ‘80s, Huerta worked as a lobbyist to improve workers’ legislative representation. During the 1990s and 2000s, she worked to elect more Latinos and women to political office and has championed women’s issues.

Ruby Bridges (1954-)

Ruby Bridges’s birth in 1954 coincided with the US Supreme Court’s landmark ruling in Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka Kansas, which ended racial segregation in public schools. Nonetheless, southern states continued to resist integration, and in 1959, Ruby attended a segregated New Orleans kindergarten. A year later, however, a federal court ordered Louisiana to desegregate. The school district created entrance exams for African American students to see whether they could compete academically at the all-white school. Ruby and five other students passed the exam.

Her parents were torn about whether to let her attend the all-white William Frantz Elementary School, a few blocks from their home. Her father resisted, fearing for his daughter’s safety; her mother, however, wanted Ruby to have the educational opportunities that her parents had been denied. Meanwhile, the school district dragged its feet, delaying her admittance until November 14. Two of the other students decided not to leave their school at all; the other three were sent to the all-white McDonough Elementary School.

Ruby and her mother were escorted by four federal marshals to the school every day that year. She walked past crowds screaming vicious slurs at her. Undeterred, she later said she only became frightened when she saw a woman holding a black baby doll in a coffin. She spent her first day in the principal’s office due to the chaos created as angry white parents pulled their children from school. Ardent segregationists withdrew their children permanently. Barbara Henry, a white Boston native, was the only teacher willing to accept Ruby, and all year, she was a class of one. Ruby ate lunch alone and sometimes played with her teacher at recess, but she never missed a day of school that year.

While some families supported her bravery—and some northerners sent money to aid her family—others protested throughout the city. The Bridges family suffered for their courage: Abon lost his job, and grocery stores refused to sell to Lucille. Her share-cropping grandparents were evicted from the farm where they had lived for a quarter-century. Over time, other African American students enrolled; many years later, Ruby’s four nieces would also attend. In 1964, artist Norman Rockwell celebrated her courage with a painting of that first day entitled, “The Problem We All Live With.”