Althea Gibson

Althea Gibson was born in South Carolina, though it was in Harlem, New York City where she first fell in love with tennis

Gibson’s had skill as well as various mentors throughout her tennis career that assisted in her becoming the first Black woman to win the U.S. Nationals, French Championship, and Wimbledon

Gibson also played golf later in life, paving the way for other African Americans and women in the sport

"I want the public to remember me as they knew me: athletic, smart, and healthy... Remember me strong and tough and quick, fleet of foot and tenacious,” Althea Gibson, n.d.

Early Life: The Makings of a Champion

Althea Gibson was born on August 25th, 1927, to sharecroppers Daniel and Annie Bell Gibson. The family lived in Silver, South Carolina, though Daniel would soon take his wife and child up north to Harlem, New York, in search of better opportunities. Gibson was the oldest of four - with three sisters and one brother entering the picture following the family’s move to Harlem.

Gibson recognized her love of tennis early on in life. She loved a variety of sports growing up, with much of her time spent playing in her neighborhood. When it came to academics, however, the same could not be said --she began to skip classes as early as 12 years old (PBS 2015). Sports provided her with the stimulation she did not receive at school. Basketball was one of the first sports she played, though shortly after she learned to play paddle tennis (a modified version of tennis). She played in public recreation programs and eventually began to compete in tournaments such as the New York City women’s paddle championship, where Gibson won at 12 years old (International Tennis Hall of Fame). Her skill was recognized by Buddy Walker - a coach with the Police Athletic League and Police Department. Walker introduced her to traditional tennis and took her to the Harlem River Tennis Courts to try her hand at the sport.

As she progressed in her tennis practice, Gibson excelled. Walker ultimately brought her to the Cosmopolitan Tennis Club in Harlem where she had no shortage of support, as those at the Cosmopolitan “chipped in to provide her a junior membership and lessons by the club professional,” (Greater Wilmington Sports Hall of Fame). Additionally, Gibson met another figure crucial to her journey at this time - her first tennis coach, Frederick Johnson. She then played in the American Tennis Association (ATA), which is the “oldest African American sports organization in the United States” (Greater Wilmington Sports Hall of Fame). Gibson was the number one ATA player for seven years in a row. At the age of 17, she had won her first junior national championship. She won again the following year. By the age of 18, she had dropped out of high school (PBS 2015).

Gibson won the New York State championship six times between 1944-1950. In 1947, she won the ATA national women’s title and would go on to have ten consecutive wins the following years. Gibson’s talent garnered the attention of prominent figures. In 1946, amid Gibson’s many tennis wins, African American physicians Dr. Hubert Eaton of and Dr. Robert W. Johnson took notice of her passion for and mastery of the sport. Johnson mentored and supported her, while Eaton encouraged her to live with him in Wilmington, North Carolina (Greater Wilmington Sports Hall of Fame, International Tennis Hall of Fame). While there, she returned to high school and worked toward her degree. After earning her degree, she enrolled at Florida A&M University. In 1955, she received her bachelor’s from FAMU at the age of 27 (PBS 2015).

Breaking Barriers

Within the world of Black tennis, Gibson dominated. However, in a country segregated by race, she was denied opportunities outside of the ATA that were afforded to white tennis players. Gibson was not the only one tired of the fact that she was barred from engaging in her craft on a larger scale. Others began to lobby on her behalf in 1950, with white tennis players such as Alice Marble and Sarah Palfrey advocating for her. Marble wrote in support of Gibson in American Lawn Tennis, proclaiming “If Althea Gibson represents a challenge to the present crop of players, then it’s only fair that they meet this challenge on the courts,” (International Tennis Hall of Fame). Though slow, movement to include Gibson began to increase following Marble and Palfrey’s support.

In the spring of 1950, she competed in the Eastern Lawn Tennis Association Grass Court Championships located in Orange, New Jersey. This competition was prestigious. Gibson made it to the second round before losing to her opponent. August of that same year, Gibson was permitted into the U.S. Nationals where she made history as the first African American to compete. When asked how she felt about competing by friend Sarah Palfrey, Gibson confidently stated: “I am not afraid of any of these players,” (International Tennis Hall of Fame).

At the U.S. Nationals, she made it to the second round and competed against Wimbledon champion Louise Brough. This match was marked by unfortunate events, with “torrential rain and a massive thunder and lightning storm [rolling] in,” (International Tennis Hall of Fame). The match was postponed. Once resumed, Gibson was defeated by Brough. A year later, Gibson went international and competed in Montego Bay. Jamaica. That summer, she also became the first African American to play at Wimbledon - a tennis tournament that was founded in 1877. She lost, though the best of her tennis career was yet to come.

Making Waves at Wimbledon and Beyond

Years later in 1956, Gibson won the French Championships. This propelled her into international acclaim, as she was also the first African American to win. In 1957, she would achieve one of the most celebrated parts of her career: winning both that year’s Wimbledon tournament (both doubles and singles) in addition to the U.S. Nationals. In each of the competitions, she was the first African American to win (Schwartz). After her Wimbledon win, she received the Venus Rosewater Dish from Queen Elizabeth II. That night, she then attended the Wimbledon Ball (Jacobs 2022). At the Nationals, Gibson was presented with the trophy by Vice President Richard Nixon. Overjoyed at her successes, New York City welcomed her with a parade (Greater Wilmington Sports Hall of Fame). As if these were not stunning accomplishments all on their own, Gibson would go on to repeat each of these wins in 1958.

Associated Press named her Female Athlete of The Year in 1957 and 1958. Those same years, she was also on the Wightman Cup U.S. women team. As of 1957, they defeated the United Kingdom; ultimately, Gibson was presented with a medal in Pakistan for her contributions to the team (National Museum of African American History and Culture). In 1958, she decided to no longer engage in amateur matches and sought out professional opportunities to make ends meet. Her experiences then became varied, including: “touring with the Harlem Globetrotters and played paid exhibition matches. Branching out to other areas, she recorded a jazz album for Dot Records, appearing on The Ed Sullivan Show, and even landed a role in a John Wayne/John Ford movie, The Horse Soldiers (1959)” (PBS 2015).

Though she played for a decade more, Gibson transitioned from a tennis player to a tennis teaching pro in 1958. In the early 1960s, Gibson also tried her hand at golf. During this time, she became the first black golfer in the Ladies Professional Golf Association (LPGA) and played 171 events from 1963-1977. Though she did not have nearly the same amount of success as she had once had with tennis (she never won a golf tournament), her involvement in the sport undoubtedly paved the way for other people of color (Alvarez 2017). During this time, Gibson also married twice. Once in 1965 to William Darben (the couple divorced in 1975) and then to previous tennis coach Sydney Llewellyn in 1983. Llwellyn and Gibson split in 1988, though they remained close friends (PBS 2015).

While Gibson broke barriers in tennis and golf, she was not without critique. Throughout her career, some commentators took issue with her race and gender, expecting “timidity” and “finesse,” of her tennis playing (National Museum of African American History and Culture). Gibson, however, was an assertive and dynamic player who was unconcerned with ideas of femininity – especially as far as tennis was concerned. Other critics felt that she was not vocal enough about the struggled faced by African Americans, even as she herself experienced racial discrimination. Gibson did not actively attend or participate in rallies and protestsIt is said that, following her big wins in 1957, “… she was denied rooms at hotels. One refused to book reservations for a luncheon in her honor,” (Jacobs 2022, Schwartz). Though difficult to experience, Gibson asserted that she did not care (Schwartz). She remained committed to tennis, confident that her mastery of the sport spoke for itself in opening doors for others in her community.

Later Life and Legacy

Despite her skill, recognized through trophies and emphasized by other professional players alike, life was not always smooth sailing for Gibson. Between the discrimination she faced, and the financial hardship brought on following her career in tennis, Gibson was no stranger to struggle. She passed away in 2003 at the age of 76 while living in East Orange, New Jersey, due to respiratory failure. In the wake of her passing, her impact in the world of sports can be seen directly by examining the careers of many players such as Arthur Ashe, Zina Garrison and Serena and Venus Williams (Jacobs 2022).

Gibson’s contributions have also been recognized on an even larger scale, as she was named to the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1971, the Women’s Sports Hall of Fame in 1980, and the Black Athletes Hall of Fame in 1974 (Greater Wilmington Sports Hall of Fame). Additionally, as of 2022, 143rd Street in Harlem was renamed Althea Gibson Way (Jacobs 2022). A life-size statue of a teenage Gibson is set to be placed at the end of the block (Jacobs 2022). In 2025, a United States quarter depicting Gibson will enter circulation as part of the American Women Quarters Program. Her impact has been celebrated far and wide, though it is her own words that sum up her life and legacy best: “I always wanted to be somebody. If I made it, it’s half because I was game enough to take a lot of punishment along the way and half because there were a lot of people who cared enough to help me.”

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Gibson pictured at New York City Hall (Photograph)

Caption: Gibson is pictured leaving city hall in New York City following various tennis wins in Europe.

Primary Source Analysis Questions:

-

Who do you think took this image? Why?

-

What do you notice about this photograph?

-

What do you wonder about who Gibson is surrounded by in this image?

Caption: This video depicts Gibson winning both Wimbledon and the U.S. Nationals, shaking hands with opponents, and holding her trophies.

Primary Source Analysis Questions:

-

What words would you use to describe the emotions Gibson likely felt when winning each of the tournaments displayed in the video clip?

-

What can you learn from watching this video?

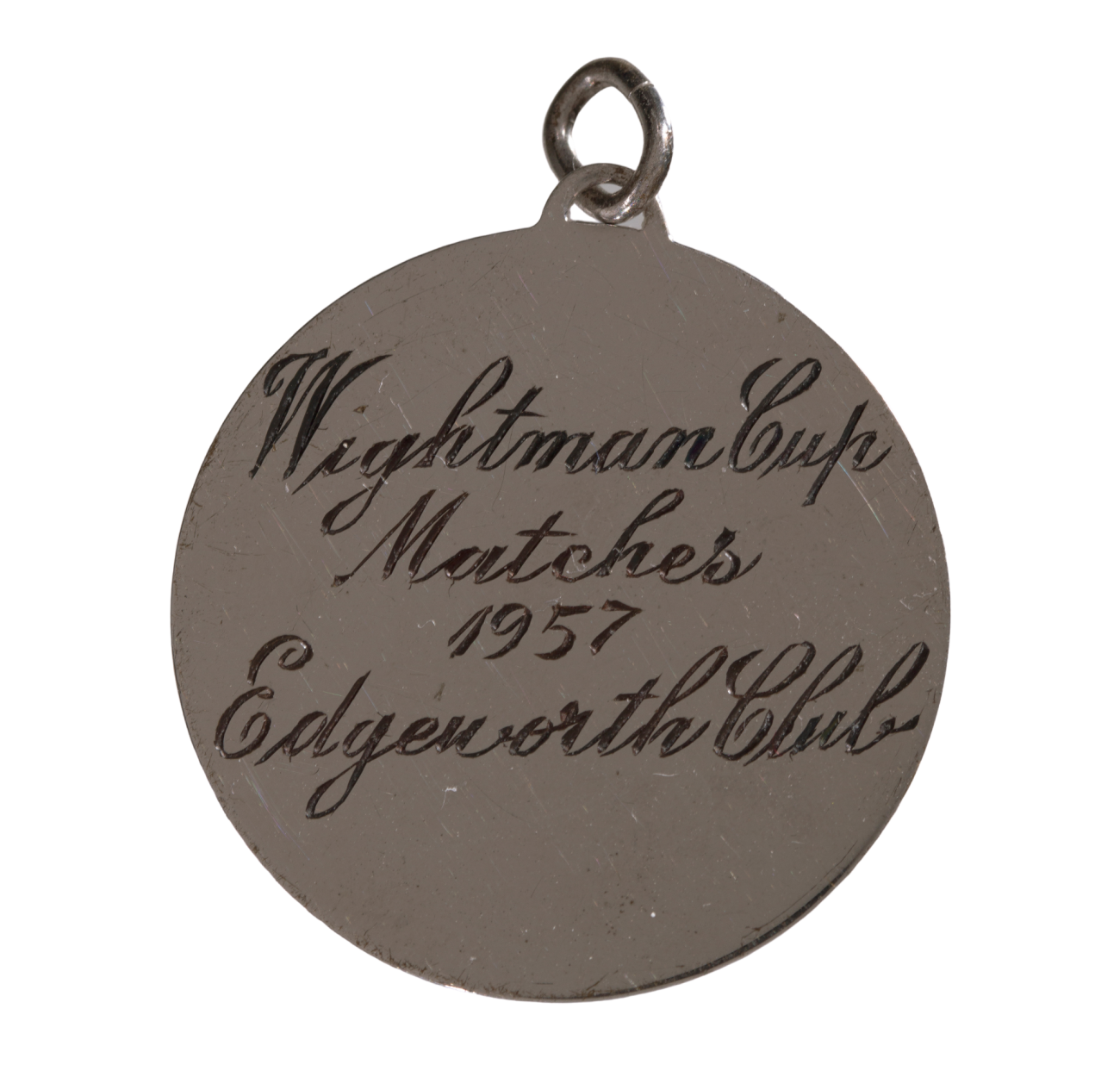

Gibson’s Wightman Medal (Photograph)

Caption: Two images depicting the front and back of the medal that Gibson received following victory at the 1957 Wightman Cup.

Primary Source Analysis Questions:

-

What questions arise for you when examining these images of Gibson’s medal?

-

Why are personal objects important in understanding the significance of a historical figure?

Ed Sullivan Show Appearance (Video)

Caption: This video is from July 14, 1957, and shows Gibson in conversation with talk show host Ed Sullivan regarding her successes as a tennis player.

Primary Source Analysis Questions:

-

Following learning more about Gibson through this biography, what word, phrase, or sentence from this clip did you find most interesting? Why?

-

Based on the clip, what is something that Gibson cared about?

Educator Notes

This resource outlines different lenses that students can examine through primary resources. There is no specific order to use the columns in. The questions students develop through their examination are meant to encourage further research and curiosity. Educators can then propose other activities (as outlined in the resource) that help students further contextualize different - but related - primary sources.

This is a blank version of the previous link. Educators can create their own specific sample questions (most likely based on the medium of the primary source to have students answer in each column), or simply have students fill out this document with the guidance of the original document.

“Althea Gibson ~ Tennis Champion Althea Gibson Biography.” PBS, September 9, 2015. https://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/althea-gibson-preview-althea/3927/.

“Althea Gibson.” Greater Wilmington Sports Hall of Fame. n.d. https://gwshof.com/project/althea-gibson/.

“Althea Gibson.” International Tennis Hall of Fame. n.d. https://www.tennisfame.com/hall-of-famers/inductees/althea-gibson.

Alvarez, Anya. “The Lesser-Known History of Althea Gibson the Golfer.” ESPN, February 20, 2017. https://www.espn.com/espnw/culture/story/_/id/18724493/the-lesser-known-history-althea-gibson-golfer.

Jacobs, Sally H. “Before Serena, There Was Althea.” The New York Times, August 25, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/25/nyregion/althea-gibson-tennis-harlem.html.

“Leveling the Playing Field: Althea Gibson.” National Museum of African American History and Culture, July 15, 2020. https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/leveling-playing-field-althea-gibson.

Schwartz, Larry. “Althea Gibson Broke Barriers.” ESPN. n.d. https://www.espn.com/sportscentury/features/00014035.html.

Main image credit:

Seawell, Wallace. “Photograph of Althea Gibson.” 1959. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

MLA – Dawson, Shay. "Althea Gibson." National Women's History Museum. National Women's History Museum, 2024. Date accessed.

Chicago - Dawson, Shay. “Althea Gibson." National Women's History Museum. 2024.

“Althea Gibson: First Black Tennis Champion - Fast Facts | History.” YouTube, January 15, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2l5fVhwbjGA.

Gibson, Althea. I Always Wanted to Be Somebody. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1958.

For further information or questions, please contact history@womenshistory.org.