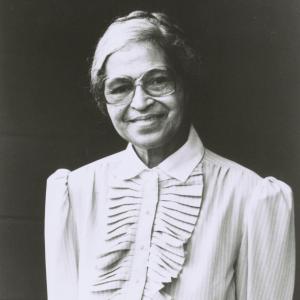

Beyond the Bus Boycott: Rosa Parks' Activism Before and After 1954

Guiding Question: How can activists and activism evolve over time?

Big Idea: Lifelong Activism

Students will analyze Rosa Parks' evolving activism during the Black Freedom Movement using primary source sets created from the Library of Congress exhibit "Rosa Parks: In Her Own Words.” Students will use the evolving hypothesis strategy to answer the focus question. They will develop an initial hypothesis, analyze primary sources using the Library of Congress Observe-Reflect-Question tool, and then return to the focus question to either adjust or defend their initial hypothesis.

“To reckon with Rosa Parks, the lifelong rebel, moves us beyond the popular narrative of the movement’s happy ending with the passage of the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act to the long and continuing history of racial injustice in schools, policing, jobs, and housing in the United States and the wish Parks left us with—to keep on fighting.” From Jeanne Theodaris and Say Burgin, "Ten Ways to Teach Rosa Parks," History Now 54 (Summer 2019), https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-now/journals/2019-07/african-american-women-leadership.

Rosa Parks spent a lifetime challenging systemic inequality throughout the United States and the world. Yet her legacy is often simplified to a seamstress who took a quiet stand on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama on December 1, 1955. This lesson challenges students to explore a fuller history of Rosa Parks’ role in the Black Freedom Movement, drawing upon primary sources from the Library of Congress exhibit “Rosa Parks: In Her Own Words.” Students will consider how Parks’ activism spread from the South to the North, how she battled a myriad of issues including sexual violence, housing segregation, police brutality, and voting restrictions, and how her work extended into the late 20th century. Students will use the evolving hypothesis and Observe-Reflect-Question strategies to answer the focus question How did Rosa Parks' activism evolve during the Black Freedom Movement?

One 45-minute class period.

- Students will be able to identify the Black Freedom Movement as a continuum of Black protest.

- Students will analyze continuities and changes in the activism of civil rights leader Rosa Parks.

- Students will develop evolving historical hypotheses based on primary source sets.

- Students will develop an appreciation for Black women’s leadership in the Black Freedom Movement.

Students should have a broad understanding of the Civil Rights Movement. Consider assigning videos from the Brown University Choices Program “Freedom Now: The Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi” for HW prior to the lesson to build this understanding.

- “Video Collection: The Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi.” Choices Program, Brown University. https://www.choices.edu/video-playlist/?unit=405.

- Library Of Congress Exhibits Office. “Rosa Parks: In Her Own Words.” Library of Congress. December 5, 2019. Video. https://www.loc.gov/item/2024696665/.

- “Teacher’s Guide: Analyzing Primary Sources.” Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/static/programs/teachers/getting-started-with-primary-sources/documents/Analyzing_Primary_Sources.pdf

- Primary source sets created from the Library of Congress exhibit “Rosa Parks: In Her Own Words,” https://www.loc.gov/exhibitions/rosa-parks-in-her-own-words/about-this-exhibition/ (see attached documents)

Warm Up: Introduction to the Black Freedom Movement and Rosa Parks’ Activism (5 minutes)

- The teacher will introduce the lesson by defining the Black Freedom Movement:

- The Black Freedom Movement is a distinct era in the African American struggle for civil and human rights that began in the mid-1940s with a surge in public protest and ended in the mid-1970s with a shift in emphasis toward electoral politics. It encompasses two of the most unique and enduring periods of Black activism. The first is the civil rights movement, which resulted in the elimination of Jim Crow laws in the South and the upending of Jim Crow customs in the North. The second is the Black Power movement, which not only expanded on the gains of the civil rights movement but also elevated African American racial consciousness, forever changing what it meant to be Black. Reference: Hasan Kwame Jeffries, “Black Freedom Movement,” in Erica R. Edwards, Roderick A. Ferguson, and Jeffrey O.G. Ogbar, Keywords for African American Studies (New York: NYU Press, 2018), 21.

- Explain that the Black Freedom Movement represents a continuum of Black protest that is both chronologically and thematically wider and deeper than traditional narratives of the Civil Rights Movement with which students may be familiar.

- Explain that today students will study Rosa Parks’ role in the Black Freedom Movement in order to widen and deepen their understanding of her civil rights activism. They will also consider how her activism changed over time. Today’s lesson should complicate and might challenge their prior knowledge of Rosa Parks.

Activity: Evolving Hypothesis and Primary Source Analysis (40 minutes)

- Initial Hypothesis (10 minutes)

- Show students the introduction video to the Library of Congress exhibit “Rosa Parks: In Her Own Words.”

- Ask students to develop an initial hypothesis of 1-2 sentences that answers the focus question: How did Rosa Parks' activism evolve during the Black Freedom Movement? The hypothesis should include an argument and a line of reasoning. Encourage students to consider the term “evolve,” which implies that Parks’ activism extended beyond the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

- Primary Source Analysis Rotation (20 minutes)

- Break students into groups of 4.

- Give each group a set of primary sources created from the Library of Congress exhibit “Rosa Parks: In Her Own Words.” 2 primary source sets are attached to the lesson. **Please note: sources include references to racial and sexual violence.

- Ask groups to distribute one source to each student.

- Rotations

- Round 1: students receive 3 minutes to analyze their initial primary source. Students should apply the Library of Congress analysis tool of Observe- Reflect-Question to their source and write in the margins around the source.

- Rounds 2-4: students rotate their primary sources to the right and receive 3 minutes to analyze their next source. Students should continue to apply the Observe-Reflect-Question tool. They may add elaboration (adding a detail), a new point (adding something that was missing), or a connection (adding a relationship to a previous note) (Project Zero +1 Routine).

- Rotate until every group member has analyzed each source.

- Allow a few minutes for students to review group analysis notes after completing rotations.

- Evolving Hypothesis (10 minutes)

- Ask students to review their initial hypotheses for the focus question How did Rosa Parks' activism evolve during the Black Freedom Movement?

- Ask students to consider what adjustments are needed for their initial hypotheses based on the primary sources they analyzed.

- Did the initial hypothesis fully reflect Rosa Parks’ contributions to the Black Freedom Movement?

- Did the initial hypothesis fully reflect how Rosa Parks’ contributions to the Black Freedom Movement changed over time?

- Ask students to modify their hypotheses based on the primary source analysis.

- Ask a few students to share their initial and final hypotheses. Compare and contrast hypotheses. An important historical understanding that should emerge is Rosa Parks’ legacy as a lifelong activist differs from her traditional portrayal in narratives of the Civil Rights Movement.

Ask students to complete a written reflection:

- How did the lesson challenge and/or complicate your prior understanding of Rosa Parks’ civil rights activism?

- Why do you think there was information that you found in Rosa Parks’ documents that are not always included in accounts of Rosa Parks’ life?

- How does Rosa Parks’ activism reflect the continuum of Black protest in the Black Freedom Movement?

- How does Rosa Parks’ activism reflect the ways that Black women contributed to the Black Freedom Movement?

Consider starting the next class with a discussion of student responses.

Suggested modifications:

- If your students are unfamiliar with the Library of Congress Observe-Question-Reflect tool, consider doing a class warm up using the iconic 1956 photograph of Rosa Parks being fingerprinted: https://www.loc.gov/item/today-in-history/december-01/. Project an image of the photograph and note student responses so they are visible to the class. Encourage students to go back and forth between the Observe-Question-Reflect columns.

Lesson extensions

- Ask students to develop a research question related to Rosa Parks’ activism throughout the Black Freedom Movement. Use resources from the Right Question Institute, such as the Question Formulation Technique (free sign up required for Right Question Institute resources): https://rightquestion.org/resources/qft-card-template/

Additional teacher resources

- Theoharis, Jeanne. The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks. Boston: Beacon Press, 2015.

- Theodaris, Jeanne, and Say Burgin. "Ten Ways to Teach Rosa Parks." History Now 54 (Summer 2019). https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-now/journals/2019-07/african-american-women-leadership.

- https://blogs.loc.gov/teachers/2017/12/using-the-rosa-parks-collection-to-foster-student-inquiry-of-parks-depictions-in-civil-rights-narratives-part-2/

- https://blogs.loc.gov/teachers/2017/12/using-the-rosa-parks-collection-to-foster-student-inquiry-of-parks-depictions-in-civil-rights-narratives-part-1/

C3 Standards:

- D2.His.2.9-12. Analyze change and continuity in historical eras.

- D2.His.3.9-12. Use questions generated about individuals and groups to assess how the significance of their actions changes over time.

- D2.His.16.9-12. Integrate evidence from multiple relevant historical sources and interpretations into a reasoned argument about the past.

This biography is sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University. Content created and featured in partnership with the TPS program does not indicate an endorsement by the Library of Congress.

For further information or questions, please contact history@womenshistory.org.