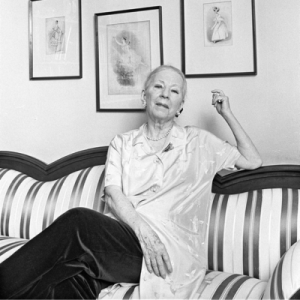

Agnes de Mille

Agnes de Mille was one of the preeminent American choreographers of the twentieth century. Entering a field dominated by men, de Mille created a distinct American style of dance and choreographed some of the most beloved American ballets. She remains an inspiration to dancers and choreographers.

Agnes de Mille was born on September 18, 1905 in the Morningside Heights neighborhood in Manhattan, New York. She was the first child born to William Churchill de Mille, a famous and successful playwright, and Anna George, the daughter of one-time progressive New York mayoral candidate and reformer, Henry George. As children, de Mille and her younger sister Margaret were quite dramatic and liked to give piano recitals and stage small productions for their family and friends. Yet de Mille’s parents refused to let her take dance lessons, arguing dancers had poor reputations.

In 1914, de Mille moved to Hollywood to follow her father. William had moved to Hollywood in order to try and "make it" like his younger brother, Cecille B. DeMille (the famous director and producer). While her parents still did not allow de Mille to take dance lessons, she and her sister did get to see dance performances by some of the great female dancers of the era, including Russian prima ballerina Anna Pavlova and Ruth St. Denis, one of the founders of American modern dance. De Mille credited these performances with inspiring her to want to become a dancer. When Margaret’s arches fell and a doctor suggested she take dance lessons as a form of recuperation, de Mille convinced her parents to let her join.

De Mille attended the private Hollywood School for Girls and then matriculated to the University of California at Los Angeles. Majoring in English Literature, de Mille continued to dance. She once had a professor tell her she was “too fat” to be a dancer. De Mille was undeterred. She graduated cum laude at age 19 in 1924. Around the time of her college graduation, de Mille’s parents divorced and she moved back to New York with her mother and sister.

Back in New York, de Mille began looking for work as a dancer. Unable to find work in a theater, she began choreographing solo dances for herself. These were well reviewed but not financially successful. In order to jump start her career, de Mille and her mother moved to London. There she joined the renowned Rambert Ballet Club, created by Dame Marie Rambert—a Polish-British dancer, teacher, and choreographer. As a member, de Mille danced with many future dance luminaries. While she did not earn great fame herself, the experience left a lasting artistic impression on her.

Her first success was choreographing the dance sequences for the 1936 film, Romeo and Juliet. In November 1938, de Mille returned to the U.S., first touring with Joseph Anthony and Sybil Shearer, two important names in the world of ballet and modern dance. When the Ballet Theatre (now the American Ballet Theatre, ABT) began in 1939, de Mille was invited to be a charter member. She created her first ballet for the group in 1940, Black Ritual. The ballet was the first production to use African American ballet dancers.

Her career skyrocketed beginning in 1942 when she was asked to choreograph a ballet for the preeminent Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. Given considerable creative control, she created and danced in Rodeo. Set to a score by American composer Aaron Copland, Rodeo is considered the first American ballet, incorporating cowboy motifs and tap dance for the first time. Rodeo was a critical and commercial success and premiered at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City on October 16, 1942. De Mille received 22 curtain calls and standing ovations, the ballet toured the country, and it is still performed today.

The success of Rodeo also led de Mille to her next choreography job. Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein, the successful musical theater duo, saw the production and approached de Mille about choreographing the dances for their next musical, Oklahoma! (1943). It remains one of the most successful musicals in American history. She was also involved with the 1955 film adaptation.

In 1943, de Mille married Walter Foy Prude, an officer in the Aviation Ordinance, in a ceremony in Beverly Hills. Prude was sent overseas during WWII, and de Mille followed her husband at the end of the war to choreograph a film in London. The couple had a son, Jonathan de Mille Prude.

After her success with Rodeo and Oklahoma!, De Mille was almost constantly working. She choreographed multiple musicals and ballets for ABT. Her choreography for the musical Brigadoon (1947) earned de Mille her first Tony Award. That same year, she began rehearsals for Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Allegro (1947), for which she acted as director and choreographer, the first time a choreographer and a woman held both roles simultaneously on Broadway. She continued to work continuously throughout the 1950s.

Beyond choreography, de Mille was also gaining a reputation as a speaker and advocate for the arts. In 1959, de Mille and others created the Society of State Directors and Choreographers (now the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society), an independent national labor union to represent theater directors and choreographers in the U.S. It was the first union of its kind and de Mille was president and the only female head of a labor union for a time. In November 1962, she advocated for the arts in a congressional hearing; her speech convinced President Kennedy to appoint her to the National Advisory Committee on the Arts, established in 1963, and the forerunner for the National Endowment for the Arts. She spoke in front of Congress two more times. In 1974, she created the Agnes de Mille Heritage Dance Theatre at the North Carolina School of the Arts in Winston-Salem, NC. The company made numerous successful national tours.

On May 15, 1975, de Mille suffered a cerebral hemorrhage just before she was about to go on stage to give a lecture. She recovered, but stopped choreographing new pieces, instead focusing her attention on lecturing and overseeing revivals of her work. She also continued to win numerous awards, including New York City’s Handel Medallion (the most distinguished civilian honor in NYC), a Kennedy Center Honor in 1980, a National Medal of the Arts in 1985, 17 honorary degrees, two Tony Awards, a 1987 Emmy, and many others. She also wrote 11 books and several articles.

Agnes de Mille died on October 7, 1993 in New York City. Her work continues to be beloved by audiences and inspires new generations of dancers and performers.

“Agnes de Mille,” American Ballet Theatre, https://www.abt.org/people/agnes-de-mille/.

“Agnes de Mille’s Biography,” Agnes de Mille Working Group, https://www.agnesdemille.com/short-biography-of-agnes-de-mille-1.

“Agnes de Mille,” Kennedy Center, https://www.kennedy-center.org/artists/d/da-dn/agnes-demille/.

Jack Anderson, “Agnes de Mille, 88, Dance Visionary, is Dead,” New York Times, October 8, 1993, https://www.nytimes.com/1993/10/08/obituaries/agnes-de-mille-88-dance-visionary-is-dead.html.

MLA – Rothberg, Emma. “Agnes de Mille.” National Women’s History Museum, 2021. Date accessed.

Chicago – Rothberg, Emma. “Agnes de Mille.” National Women’s History Museum. 2021. www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/agnes-de-mille.

Photo Credit: Lynn Gilbert, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=51678343.

“Agnes de Mille,” Broadway: The American Musical, PBS, https://www.pbs.org/wnet/broadway/stars/agnes-demille/.

Agnes de Mille, Dance to the Piper (1951).

Agnes de Mille Papers, Sophia Smith Collection, SSC-MS-00046, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts. https://findingaids.smith.edu/repositories/2/resources/445.

de Mille, Agnes, 1905-Collection, (S) *MGZMD 37, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. http://archives.nypl.org/dan/19685.