Mae Jemison

Born in 1956, Mae Jemison received degrees in Chemical Engineering in African American Studies and went on to become a medical doctor and officer in the Peace Corps.

In 1983, after watching Sally Ride, Jemison decided to apply to the astronaut program at NASA. On September 12, 1992, Jemison went into orbit aboard the space shuttle Endeavour as the first African American woman in space.

Jemison left NASA in 1993, continuing to work for the benefit of others as an educator, entrepreneur, and author.

“Sometimes people want to tell you to act or to be a certain way. Sometimes people want to limit you because of their own imaginations” Mae Jemison, "Mae Jemison: Coming In From Outer Space." Ebony, December 1992.

Childhood: Alabama to Chicago

Mae Carol Jemison was born in Decatur, Alabama on October 17, 1956. She spent her first three and a half years in the small Alabama town. Her mother, unhappy with job opportunities in the South, joined the Great Migration and moved to Chicago, Illinois. Her parents valued education. Charlie Jemison, a maintenance supervisor, and Dorothy Jemison, a teacher, took their children to Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry and the Field Museum of Natural History to visit and learn. As soon as she learned to read, Mae checked out science books from the library, reading about evolution, dinosaurs, stars and planets.

When she was eight years old her mother signed her up for beginner ballet at the Sadie Bruce Dance Academy. This started her life-long love of dance. She continued to take modern dance classes at the Jane Addams Hull House Association Community Center. The complicated dance routines challenged Jemison to understand shape, form, and rhythm. And she gained an appreciation for hard work, physical strength, and grace (Jemison 42).

After a confrontation between her brother and members of the Blackstone Rangers street gang, her parents decided to move from the mostly African American neighborhood of Woodlawn to Morgan Park. Jemison’s family was the first Black family on their block. Morgan Park High School and a couple of the elementary schools had been historically integrated, but the residential areas were not.

Excelling in science during elementary school, Jemison created projects focusing on the evolution of life on planet Earth. She learned about astronomy while visiting the Adler Planetarium in Chicago; viewing stars from the perspective of the Southern Hemisphere and being fascinated looking at what the sky looked like thousands of years ago.

Jemison entered Morgan Park High School and excelled in her classes while also participating in musical theater. For one of her science projects, she investigated sickle cell anemia and met the chief lab technician at Cook County Hospital who went on to serve as her mentor. The science fair project won first place in a city-wide competition. Although younger than most of her peers, she was always on the honor roll and graduated in 1973 when she was 16 years old.

The Value of Education: College at Stanford & Cornell Medical School

Once Jemison graduated high school, she left Chicago to attend Stanford University in California. She served as the president of the Black Student Union. Staying true to her love of dance, she also choreographed a performing arts production called Out of the Shadows that focused on the African American experience. She studied the language of Swahili and took modern, jive, swing, Haitian, Brazilian, and African dance classes and acted in a play and musical. Jemison stated in her book, “Dance was always very important to me and I believe helped me through Stanford. I think it is the creativity, athleticism, musicality, and story narrative that must be integrated and communicated at the same time that makes dancing so invigorating and peaceful” (148). She graduated in 1977 with a Bachelor of Science degree in Chemical Engineering and a Bachelor of Arts degree in African American studies.

The next step in her educational journey would lead her to Cornell Medical School. While there, she traveled to Cuba and led a study for the American Medical Student Association. Jemison also became president of the Cornell chapter of the Student National Medical Association and helped coordinate regional health fairs. She also worked at a Cambodian refugee camp in Thailand. Jemison graduated from Cornell in 1981 with a Doctorate in Medicine. After her graduation from medical school, she interned at the Los Angeles County Medical Center and later practiced general medicine.

International Outreach: Africa and the Peace Corps

Jemison spent the summer between her second and third year of medical school in Kenya in East Africa. She said, “arriving there was really like reaching a destination I had dreamed about and moved toward all my life” (183). Her travel was supported through a study grant from the International Travelers Association and student loan money. While there, she worked for the African Medical Education and Research Foundation (AMREF), formerly known as the Flying Doctors. They travel to remote areas in East Africa to provide health services, such as surgery, to people who might otherwise go without. Jemison performed a community health survey and diagnosis and assisted with a British surgeon in a hospital. While in Nairobi, she helped with community medicine projects in the low-income area of Kawangware.

Jemison left Kenya after eight weeks to travel to Egypt, Greece, and Israel. She visited the pyramids of Giza, the bazaars of Cairo, stayed in a kibbutz, visited the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and the Wailing Wall. Jemison states of the journey, “From all these places in Egypt and Israel, all the people, the ideas, one on top of the other, Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Palestine, Israel, Romans, Nubians, and pharaohs, I began to understand the complexity of politics - and I also saw faith. I felt the wind gathering energy, and I understood that until we humans fully acknowledge how intertwined we are with one another, there will be endless suffering. Until people are willing to recognize and honestly, openly, and transparently discuss inequities, wrongs, aggression, violence, peace offerings, and history, not only will individuals suffer, but so will the planet” (193).

These experiences abroad inspired Jemison to join the Peace Corps in 1983 where she served as a medical officer for two years. Jemison was fascinated by primary care medicine in developing countries. At twenty-six years old, she became the Area Peace Corps Medical Officer for Sierra Leone and Liberia. She was responsible for the health of all US Peace Corps volunteers, staff members, and embassy personnel of Sierra Leone and the Peace Corps volunteers in Liberia. She also managed a medical office, a laboratory, pharmacy, and volunteer health training in addition to being a primary care doctor. Jemison commented about the experience, “On call twenty four hours a day, seven days a week for two and a half years, in a place that could be so unforgiving of mistakes, I gained flexibility, knowledge, interpersonal relationship skills, and an appreciation of the challenges life poses to so many people on this planet … The insights I gained into the misconceptions of lifestyles and the challenges and opportunities in poor countries nourished my imagination. I understood. What we decide to do with our talents is up to each one of us and is based on our view of life and our desires” (199).

NASA: All the Way to the Stars

On June 18, 1983 Sally Ride became the first American woman in space. This historic event paired with Jemison’s childhood fascination with space, inspired her to apply to the astronaut program at NASA in 1985. However, due to the explosion of the Space Shuttle Challenger in 1986, the program was paused. Jemison reapplied and was accepted in 1987. She was one of the fifteen people chosen for the program, out of over 2,000 applications. She was selected for NASA Astronaut Group 12.

She received her first mission on the STS-47 crew as a mission specialist aboard the Space Shuttle Endeavour. On September 12, 1992, Jemison and six other astronauts rocketed into space for their mission. With this successful launch, Mae Jemison became the first African American woman in space.

While in orbit, Jemison conducted experiments that took advantage of the microgravity environment, where objects appear to be weightless. The mission, known as Spacelab J, conducted over forty-four different experiments. According to NASA, “Materials science investigations covered such fields as biotechnology, electronic materials, fluid dynamics and transport phenomena, glasses and ceramics, metals and alloys, and acceleration measurements. Life sciences included experiments on human health, cell separation and biology, developmental biology, animal and human physiology and behavior, space radiation, and biological rhythms. Test subjects included the crew, Japanese koi fish (carp), cultured animal and plant cells, chicken embryos, fruit flies, fungi and plant seeds, and frogs and frog eggs.” The Endeavor crew made 127 orbits around the Earth and safely returned to the Kennedy Space Center in Florida on September 20, 1992.

In her book Jemison remembers, “Strange, but I always knew I’d be here. Looking down and all around me, seeing the Earth, the moon, and the stars, I just felt that I belonged right there, and in fact, any place in the entire universe” (225).

With her on her spaceflight, Jemison carried a picture of aviator Bessie Coleman. In the afterword of a book on Coleman written by Jemison, she remembers, “... I was embarrassed and saddened that I didn't learn of her until my space flight beckoned on the horizon… I wished I had known her while growing up, but then again I think she was there with me all the time,” (Rich 145).

Post NASA & Paying it Forward

Jemison continued to work for NASA as an astronaut for six years, leaving in 1993. The publicity from her historic flight provided her “a more visible platform from which to discuss the importance of individuals taking responsibility not only for themselves, but also for how they treat others and this planet” (Jemison 228).

Jemison wanted to apply her knowledge, skills, perspectives and energy in different innovative ways. She launched The Earth We Share, an international science camp. She continued to educate the future through her professorship at Dartmouth College, teaching about space technology and its benefits for developing countries. In addition, she founded the consulting company Jemison Group Inc., which focused on combining space and technology to improve daily life on earth.

In 2012, Jemison created 100 Year Starship, an initiative committed to ensuring that the capabilities for human interstellar travel beyond our solar system will exist in the next 100 years. She also serves on the Board of Directors for many organizations including the Kimberly-Clark Corp., Scholastic, Inc., Valspar Corp., Morehouse College, Texas Medical Center, Texas State Product Development and Small Business Incubator, Greater Houston Partnership Disaster Planning and Recovery Task Force, and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering. She hopes that through her work, she can help to “ensure that all people know that they have a place in this world. [And ensure that everyone] has the right and responsibility to live up to [their] individual potential and ambitions” (230).

Mae Jemison currently lives in Houston, Texas and she stands by her principles, “Everyone should benefit from the bounty of this planet and its resources, not just those already well positioned. Solutions, technologies, and systems are more sustainable and beneficial when they are built drawing upon the full range of human perspective, skills, experiences, and talents” (229). She continues to inspire learners of all ages to reach for the stars.

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Caption: Mission Specialist Mae Jemison poses in Spacelab-Japan, 1992.

Educator Notes:

Educators can use the thinking routine See Think Wonder to craft learner inquiry about this image.

Educator Notes:

Educators can use the thinking routine See Think Wonder to craft learner inquiry about this image.

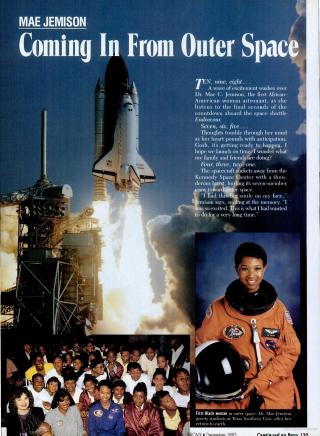

Mae Jemison in Magazines

Caption: Mae Jemison appeared in many popular magazines, included Ebony and Jet.

Educator Notes:

Educators can use the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Teacher Guide: Analyzing Newspapers as a baseline to help build inquiry. Learners can further explore with the directed questions below.

Analysis Questions for Ebony Magazine “Coming In From Outer Space” By Karima A. Haynes

- Why does Jemison believe her participation in the space shuttle flight is important?

- What does Jemison state is the connection between race and scientific research?

- What inspired Jemison to become an astronaut?

- How does Jemison approach dealing with negative racist thinking?

Analysis Questions for Ebony Magazine “Close-Up: A New Star in the Galaxy” By Marilyn Marshall

- What are the different requirements to become an astronaut?

- What personal items did Jemison bring aboard her space flight?

- Based on the articles, how would you describe Jemison’s personality?

Compare both articles:

- What do you notice about both articles?

- Who is the audience?

- Do you notice any differences in how the articles share Jemison’s story?

- What do these articles tell you about the time when Jemison went to space?

- Examine the advertisements and other articles in the issue. What does this tell you about American culture in the early 1990s? How does the content compare to what you see on the news and social media today?

Mae Jemison Ted Talk: Teach the Arts and Sciences Together

Analysis Questions:

- What is Jemison’s main idea? What examples does she use to support this?

- After learning about her background, how did Jemison’s life influence this point of view? Does your background resonate with her point of view? Why or why not?

- Mae Jemison supports teaching both the arts and sciences together. How has your own education reflected or challenged this idea? What are the benefits and drawbacks of a curriculum that integrates these two fields?

- Jemison emphasizes the importance of 'bold thinkers.' How do you think the integration of arts and sciences can contribute to the development of bold thinking? Reflect on your own experiences and how you have seen this play out in your own life or the lives of others.

-

Jemison, Mae. Find Where the Wind Goes: Moments from My Life. New York: Scholastic, 2001.

-

Rich, Doris L. 1993. Queen Bess: Daredevil Aviator. Smithsonian Institution Press.

Title Image: "Official portrait of STS-47 Mission Specialist Mae C. Jemison in LES." JSC, NASA. July 1992. https://images.nasa.gov/details/S92-40463

MLA – Mathias, Marisa. “Mae Jemison.” National Women’s History Museum, 2024. Date accessed.

Chicago – Mathias, Marisa. “Mae Jemison.” National Women’s History Museum. 2024. www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/mae-jemison.

- "Dr. Mae Jemison Becomes First Black Woman in Space." Jet, September 14, 1992.

-

Harrison, Paul Carter. Black Light: The African-American Hero. 1993. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press.

-

Hawkins, Walter L. African-American Biographies: Profiles of 558 Current Men and Women. 1992. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co.

-

Hine, Darlene Clark, ed. Black Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia. 1993. Brooklyn, N.Y.: Carlson Publishing Inc.

-

Jemison, Mae. Find Where the Wind Goes: Moments from My Life. New York: Scholastic, 2001.

-

Jemison, Mae. "Teach Arts and Sciences Together." TED. February 2002. https://www.ted.com/talks/mae_jemison_on_teaching_arts_and_sciences_together?language=fa.

-

La Blanc, Michael L., ed. Contemporary Black Biography, Volume 1. 1992. Detroit: Gale Research, Inc.

-

Lantero, Allison. "Five Fast Facts about Astronaut Mae Jemison." Department of Energy. March 3, 2016.

-

"Mae Jemison: Coming In From Outer Space." Ebony, December 1992.

-

Phelps, J. Alfred. They Had a Dream: The Story of African-American Astronauts. 1994. Novato, CA: Presidio Press.

-

Smith, Jessie Carney, ed. Notable Black Women. 1992. Detroit: Gale Research, Inc.

-

Smith, Jessie Carney, ed. Epic Lives: One Hundred Black Women Who Made a Difference. 1993. Detroit: Visible Ink Press.

-

Streissguth, Thomas. Mae Jemison. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt School Publishers, 2010.

Bessie Coleman

This biography is sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University. Content created and featured in partnership with the TPS program does not indicate an endorsement by the Library of Congress.

For further information or questions, please contact [email protected].

This biography is sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University. Content created and featured in partnership with the TPS program does not indicate an endorsement by the Library of Congress.

For further information or questions, please contact [email protected].