Juliette Gordon Low

“Today’s work is the history of tomorrow, and we are its makers.”

Juliette Gordon Low

Early Life

Juliette “Daisy” Magill Kinzie Gordon was born in Savannah, Georgia on October 31, 1860, to William Washington Gordon II and Eleanor “Nellie” Kinzie Gordon. The Gordon family acquired their wealth from the Belmont cotton plantation. During the Civil War, Gordon experienced periods of financial and food insecurity while her father fought for the Confederacy (Cordrey, p. 26). By the summer of 1865, the family was reunited and the plantation recovered economically.

As a child, Gordon preferred being outdoors, spending her summers fishing, sunbathing, sailing, and swimming (Cordrey, p. 35). She had a privileged upbringing, coming from a well-respected family of the Savannah community but Gordon’s parents encouraged her and her five siblings to be loyal, dutiful, and respectful of others (Cordrey, p. 40). These traits would later become central to the Girl Scouts’ activities and mission.

Starting at the age of 12, Gordon was sent to a few different boarding schools in both the North and South. She exceled in piano, speech, drawing, and French, but had difficulty with spelling and grammar (Cordrey, 2012). Some historians speculate that she may have had a learning disability, such as dyslexia. In spite of these difficulties, Gordon enjoyed socializing with her classmates. She joined a sorority, Theta Tau, that introduced her to a strong support system and the activity of earning badges through merit (Cordrey, p. 48).

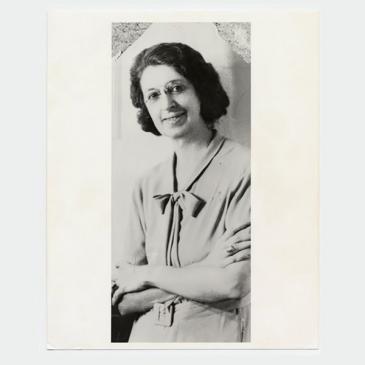

Above: Juliette Gordon Low House, birthplace of Low and historic house museum in Savannah, Georgia.

loc.gov/item/ga0010

England & the Girl Guides

In 1886, Gordon married William Mackay Low, another wealthy native of Savannah who at the time lived in England. After marrying, the couple moved to England and socialized with aristocratic families of Britain. The marriage produced no children, and the couple spent most of their time apart from each other (Georgia Historical Society, 2025). By 1905, the couple was in the processes of divorcing but, Low’s husband suddenly died, leaving the divorce uncompleted.

In 1911, Low met Lord Robert Baden-Powell, founder of the Boy Scouts and Girl Guides. Baden-Powell had recently set up the Girl Guides and suggested she work with the organization (Juliette Gordon Low Birthplace Museum, 2025). Soon after, Low went on to establish Girl Guide troops in London and rural Scotland.

Above: Portrait of Low by Edward Hughes, 1887.

commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edward_Hughes_-_Juliette_Gordon_Low_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg

From Girl Guides to Girl Scouts

Upon her return to the United States in early 1912, Low was eager to begin the Girl Guides movement in America (Juliette Gordon Low Birthplace Museum, 2025). On March 12, 1912, the first Girl Guides troop in America was founded in her hometown of Savannah, Georgia. The first Girl Guides consisted of her relatives and girls from other established families in the town.

By the Summer of 1912, the Savannah Girl Guides troop was divided into smaller units of girls called “patrols.” Each patrol was named after a flower, and they met on different days of the week. The girls learned a wide variety of skills, including map reading, first aid, cooking, knot tying, and played sports such as basketball (Cordrey, p. 207). Low also adopted the British Girl Guides’ system of awarding badges to girls who became proficient in skills (Cordrey, p. 230).

In 1913, the Girl Guides name was changed, officially becoming the Girl Scouts. That same year Low created the first national headquarters in Washington, D.C. to promote the Girl Scouts nationwide (Cordrey, p. 223). To aid in the recruiting process, the first American Girl Scout handbook, How Girls Can Help Their Country, was published in the summer of 1913. Low had adapted the handbook from the British Girl Guides handbook, How Girls Can Help to Build Up the Empire, which was written by Agnes Baden-Powell, Baden-Powell’s sister (Cordrey, p. 204). In 1914, Low’s efforts proved successful, ten Girl Scout troops registered in Washington D.C and eight Girl Scout troops registered in Chicago.

World War I

Throughout the course of World War I, Low travelled between America and Britain. Low encouraged the Girl Scouts to participate in the war effort by running soup kitchens, creating care packages for soldiers, and harvesting crops (Cordrey, p. 232). In partnership with the American Red Cross, the Girl Scouts sold white flags to raise funds for the war relief on October 12, 1914. The troops that participated in war effort came from Boston, Washington, New York, Chicago, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Savannah, Newark, Cleveland, Richmond, Cincinnati, Saint Louis, Atlanta, Detroit, San Francisco, Saint Paul, and New Orleans, reflecting Low’s impact in spreading the Girl Scouts in America (Cordrey, p. 232).

While in the United Kingdom, Low supported Belgium refugees and raised funds for British soldiers and their families. She championed the Girl Guides during the war, highlighting their roles in the war effort as important assistants for communication and household tasks (Cordrey, p. 236). The number of Girl Guide participants increased during the war, like the Girl Scouts in America.

The contributions of the Girl Scouts in the war effort resulted in President Herbert Hoover writing a letter championing the Girl Scouts and Girl Guides, supporting Belgium refugees in the UK, and raising funds for British soldiers and their families. She also worked with the American Red Cross and other US organizations to involve Girl Scouts in the war effort. Girls rolled bandages, planted gardens, canned, and sold war bonds.

Above: Low on the right, Girl Scouts Troop #1, 1917.

loc.gov/item/2016867949

International Council of Girl Guides

After the war ended in 1918, Low returned to England to continue her work with the Girl Guides and to revive their connection with the American Girl Scouts. Olave Baden-Powell spearheaded an International Council of Girl Guides and Girl Scouts in 1919. Low was in London at that time and acted as the American representative on the Council. Its aim was to expand the work of the girls’ organizations throughout the world. During the 1920s, this International Council of Girl Guides created troops in many parts of the globe, including South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and China.

For her extensive and continued work for the Girl Guides, Low was awarded the organization’s Silver Fish by Olave Baden-Powell in 1919, its highest honor. Low is one of the few Americans to have received this award. The following year, Low stepped down as President of the Girl Scouts of America and focused more of her attention on promoting the organization internationally. The organization established Low’s birthday, October 31, as Girl Scouts’ Founder’s Day in 1920.

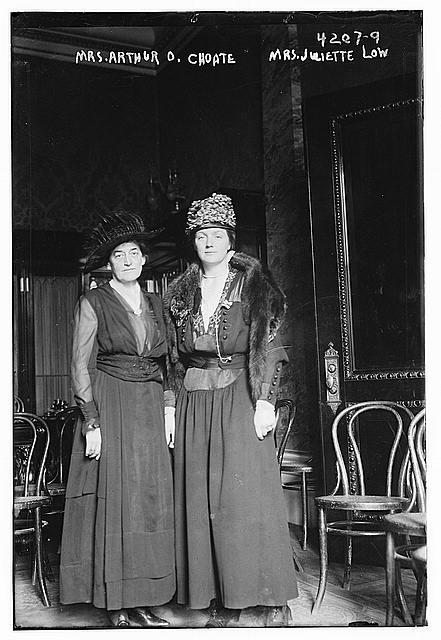

Above: Low on the left and Anne Hyde Choate (misidentified on image), leader of the Girls Scouts organization, on the right.

loc.gov/resource/ggbain.24369/

Later Years and Legacy

In the early 1920s, Low was diagnosed with breast cancer. She had several surgeries and treatments, including the ingestion of lead, to try and cure her disease. But her treatments did not work. Despite her poor and declining health, Low kept up a relentless schedule to promote and support the work of the Girl Scouts. On January 17, 1927, she succumbed to her illness and passed away. The next day at a candlelight service, hundreds of Girl Scouts attended her funeral.

Above: Low posthumously honored on US Stamp, 1948.

commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:00JulietteLow.jpg

Low has been awarded numerous posthumous awards such as induction into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1979. In 2012, President Barack Obama awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom and her birthplace is also designated as a National Historic Landmark.

Although she died over ninety years ago, Low’s legacy lives on. Today, the Girl Scouts organization is thriving around the world. As of 2017, there are over three million members and over fifty million members since its founding in 1912. The organization is self-sufficient due to its many patrons and yearly cookie sales to raise funds.

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

President Herbert Hoover’s Letter to Low, 1918

Analysis Questions

-

What does President Herbert Hoover’s letter of support for the Girl Scouts suggest about the organization’s perceived impact on American society and the war effort?

-

How did national recognition, such as Hoover’s letter, influence the growth and legitimacy of the Girl Scouts in the United States?

A Girl Scout of Red Rose Troop Book Cover, 1918

Analysis Questions

-

How does The Girl Scout of the Red Cross emphasize the role of young women in wartime service, and what values does it promote?

-

What rhetorical strategies and language does the author use to appeal to patriotism and civic duty in this source?

-

How does this document reflect broader societal expectations of women’s roles during the time it was written?

Educator Notes

The book cover image for A Girl Scout of Red Rose Troop (1918) by Amy Ella Blanchard has been included in the link above.

Educational Work of the Girl Scouts, 1921

Analysis Questions

-

How does Educational Work of the Girl Scouts define the purpose of the Girl Scouts, and what does this suggest about the organization’s goals for young women?

-

In what ways does this document connect Girl Scout activities to broader educational and social ideals of the time?

-

How does the language and tone of the text reflect societal attitudes toward girls’ education and civic responsibility in the early 20th century?

Educator Notes

Educational Work of the Girl Scouts (1921) by Louise Stevens Bryant was part of the 1918-1920 Biennial Survey of Education in the United States. The printed material in its entirety is available online at the Library of Congress website. The introduction to this work has been included in the link above.

Carry the Torch

Carry the Torch

Cordery, S. A. (2012). Juliette Gordon Low: The remarkable founder of the Girl Scouts. New York: Penguin.

Kleiber, S. H. (2012). “Juliette Gordon Low, who had no children of her own, started Girl Scouts in 1912.” The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/kidpost/juliette-gordon-low-who-had-no-children-of-her-own-started-girl-scouts-in-1912/2012/02/28/gIQA5CBO1R_story.html?utm_term=.e9dc17f4637c

Gambino, M. (2012) “The Very First Troop Leader: A New Biography Tells the Story of Juliette Gordon Low, Founder of the Girl Scouts.” Smithsonian.com http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-very-first-troop-leader-116645976/

Girl Scouts of the United States of America. (2024). “Juliette Gordon Low: A Brief Biography.” http://www.girlscouts.org/en/about-girl-scouts/our-history/juliette-gordon-low.html

Girl Scouts of the United States of America. (2016). “Timeline: Girls Scouts in History.” http://www.girlscouts.org/en/about-girl-scouts/our-history/timeline.html

Revzin, R. E. (1998). American Girlhood in the Early Twentieth Century: The Ideology of Girl Scout Literature, 1913-1930. The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy, 68(3), 261–275. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4309227

Shultz, G. D., & Lawrence, D. G. (1958). Lady from Savannah: The life of Juliette Low. J. B. Lippincott Company.

Sims, A. H., & Keena, K. K. (2010). Juliette Low’s Gift: Girl Scouting in Savannah, 1912-1927. The Georgia Historical Quarterly, 94(3), 372–387. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20788992

United States Mint. (2023, October 17). United States Mint announces designs for 2025 American Women Quarters™ Program coins. United States Department of the Treasury. https://www.usmint.gov/news/press-releases/mint-announces-designs-for-2025-american-women-quarters-program-coins

MLA – Spring, Kelly, and Corina Gonzalez. “Juliette Gordon Low.” National Women’s History Museum, 2025. Date Accessed.

Chicago – Spring, Kelly, and Corina Gonzalez. “Juliette Gordon Low.” National Women’s History Museum. 2025. www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/juliette-gordon-low.