Wilma Mankiller Celebrated in New Film

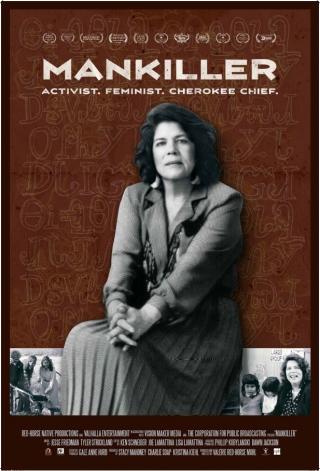

The National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) is the oldest, largest, and most representative national organization representing and advancing the interests of Native nations and peoples. Each year, NCAI selects a cohort of 3-5 Wilma Mankiller Fellows to join their staff for a paid term of 11 months. Each Fellow must have a bachelor’s degree or equivalent experience, and young AI/AN professionals or students are encouraged to apply. Each Fellow is assigned to a department based on their undergraduate degree, skills and experience, and general interests. This year, three Wilma Mankiller Fellows joined the prestigious NCAI program. In advance of a special screening of the documentary Mankiller at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, DC, the fellows were asked to share what Wilma Mankiller and the fellowship program means to them. To learn more about the documentary visit www.mankillerdoc.com.

Lorraine Basch | Puyallup Tribe of Indians | Wilma Mankiller Fellow – Policy

In contrast to the political culture of the general population, Indian Country traditionally was not led exclusively by men. Many Native nations were and are maternalistic in nature. Being from a tribe and family that was heavily impacted by assimilation policies, Wilma Mankiller was able to overcome colonial institutions that attempted to undermine her place and ability as a woman and degrade her connection to her culture. Wilma Mankiller spent her life devoted to the doctrine that change comes from the people and by the people. Her first exposure to activism came with the American Indian Movement and the Alcatraz Occupation in the late 1960s and early 1970s. It was during the time that she spent there that this young mother of two first heard people conceptualize what she had always known: that Native nations are, and have always been, inherently sovereign and fully capable of governing their own affairs.

The story of Wilma Mankiller presented in Mankiller not only is an opportunity to honor the life-time achievements of the first female Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, but also provides inspiration for all oppressed peoples. By serving as an example of what a strong minority woman can achieve, Wilma Mankiller has brought spirit back into what it means to be a Native American. After generations of US policies promoting reliance on the federal government, it was leaders like her that led Indian Country into the Native nation-building era of our societies. This notion was best explained when she said, “We need to trust our own thinking. Trust where we are going. And get the job done.” Because of Mankiller and other like-minded Indigenous leaders, Indian Country began to break free from the Federal Government’s paternalistic and oppressive policies, to charting their own self-governance courses so that we can provide for our future generations on our own terms.

The National Congress of American Indians’ Wilma Mankiller Fellowship provides young Native professionals with the opportunity to absorb Tribal advancement methods that we can then use as future leaders or bring home to our current Tribal leaders in order to promote community wellness. Part of our role as Wilma Mankiller Fellows is to learn the best practices devised by tribal leaders before us in order to build on them and eventually pass them on to the leaders of the next generation. Wilma Mankiller is not only a role model for Native Americans, but for all women yearning to rise above the paternalistic ideals of dominant society.

Yawna Allen | Cherokee/Quapaw/Yuchi | Wilma Mankiller Fellow – External Affairs

The most fulfilled people are those who get up every morning and stand for something larger than themselves. - Wilma Mankiller

There is a Cherokee concept called gadugi – which loosely means “to come together for the betterment of the entire community.” In the old days, both women and men would equally share in the labor intensive tasks of daily life. Gadugi was when the people would work together to accomplish a task, such as tending fields, to help elders and others in the community who needed it. This concept is what comes to mind when I think of Wilma Mankiller.

In so many ways, Wilma embodied this concept. When Wilma and her husband Charlie Soap helped facilitate (and worked side-by-side in) a volunteer labor effort to install 18 miles of water lines for the Cherokee community of Bell, Oklahoma, this exemplified not only a self-reliant, community-based approach to getting things done, but also provided a perfect example of servant leadership. To me, a great leader recognizes that leadership isn’t about them as an individual; but rather they view themselves simply as a conduit to help bring about a positive and lasting change for the people they serve. It was projects like those in Bell, and Wilma’s eagerness to engage the community – to make them take ownership in creating their own, more vibrant future – that speaks volumes about her character and leadership.

Although Wilma’s road was far from smooth – she often faced opposition from folks simply because she was a woman – her dedication to the people and their causes allowed her to break barriers and reintroduce the traditional equality of women and men. Her tenacity and resilience paved the way for other Cherokee women to reclaim their rightful place – and instilled a belief that they too can step up and serve their communities in a way many had long forgotten was possible.

It is an honor to serve as a Wilma Mankiller Fellow at the National Congress of American Indians, as I am fortunate to have the daily opportunity to do meaningful work for Indian Country. It also holds a special meaning for me as I can proudly say: tsitsalagi geya – I am a Cherokee woman. As I eagerly await the release of the documentary Mankiller, I hope you all are just as inspired as I am by the life and leadership of Wilma Mankiller.

Tyesha A. Ignacio | Diné (Navajo) Nation | Wilma Mankiller Fellow – Partnership for Tribal Governance

Wilma Mankiller served as the Cherokee Nation’s first female Principal Chief. She advocated for and transformed the nation-to-nation relationship between the Cherokee Nation and the federal government. What was most unique about her leadership style is that she forged a path that simultaneously empowered and restored cultural balance to her and other Indigenous communities. Her presence and influence in leadership positions inspired many people to recognize the importance of tribal sovereignty, cultural competency, and tribal self-determination and self-governance. As a Diné woman and a Wilma Mankiller Fellow at the National Congress of American Indians in Washington, DC, I view her contributions as a step forward for women, but also a step toward restoring cultural traditions. There are two quotes of hers that really resonate with me and inspire my work here in Washington, DC. The first is as follows:

No individual’s life stands apart and alone from the rest. My own story has meaning only as long as it is a part of the overall story of my people. For, above all else, I am a Cherokee Woman.

As a female Diné who pursues higher education and leadership roles, I do it for my people above myself. My nation and many other Native nations have survived decades of historical trauma and deserve to be fought for and recognized as capable entities. Wilma Mankiller advocated on behalf of her people to improve their lives. She saw where their strengths lay and personified their resiliency, tenacity, and cultural values. She taught us that being a sovereign nation means that our government is reflective of our traditions, that it serves our people and their needs, and that it creates opportunity for our people to live and thrive within our cultures. This leads to my second favorite quote:

We know our problems – we live with them every day. Our strength lies in the fact that despite the fact that the most powerful force in the world once tried to wipe us off the face of the earth and then instituted a set of policies designed to make sure that we no longer existed as cultures and as people, we are still here.

Wilma Mankiller acknowledged the struggles that Native people face and worked toward changing that narrative through community development; true, inherent sovereignty in practice; and the creation of many youth education initiatives. She dedicated her life to the advancement of the Cherokee people and Native nations, and through this pursuit set an example for millions to follow. Her legacy will continue on through the many people who carry on her work, notably her children, her husband, and the Cherokee Nation.