Women's Temperance Societies

Para leer este artículo en español, presione aquí.

Alcohol prohibition was not a part of the Puerto Rican people's agenda or that of colonial officials when Puerto Rico changed hands from Spain to the United States in 1898. However, publicly legitimized sectors of society, such as historically Protestant churches, the Free Federation of Workers, freemasons, theosophists, spiritualists, and free thinkers had already started strengthening the anti alcohol discussion. Through their writings and keen power of persuasion, they gave birth to an intellectual elite in 1874 that supported the movement. Doctors and writers alike from prominent cultural organizations, such as El Ateneo, Puerto Rico's oldest historical center, linked the virtue of temperance with modernity and progress.

Between 1898 and 1915, rejecting excess alcohol consumption as a means of realigning society was occasionally discussed on the Island. Drinking was considered as a societal hindrance, a moral affront, and a problem associated with those of lesser education and means. This advocacy for alcohol moderation would ultimately become transform into a call for alcohol suppression when American missionaries suggested the possibility of fully implementing prohibitionist measures on the Island.

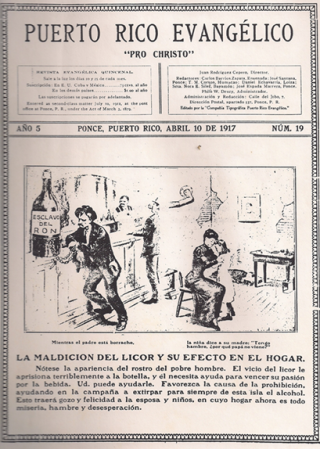

A host of Puerto Rican Protestant ministers at the time emerged launched themselves as the first leaders of this prohibitionist approach. They spread their views throughout the Island by preaching temperance views in the countryside and sugar plantations, and publishing articles in the Puerto Rico Evangelical and the socialist press. At the time, public opinion was divided between those that defended temperance and those that pointed to the growing normalization of alcoholism. Despite these discrepancies, the two factions agreed on the fact that Puerto Ricans did, in fact, consume alcohol and that the quantities and contexts in which alcohol was consumed largely differed across the Island.

Beginning in 1915, American Protestant organizations, backed by the support of established Protestant churches in the Island, the Free Federation of Workers, and some Masonic lodges promoted the local adoption of prohibitionist measures before Congress. In 1916, a sector of Protestant women established a series of Leagues of Temperance under the auspice of the Women Christian Temperance Union led by Annie Robbins. The Leagues' membership, estimated at 315 women, consisted of two factions: ten American women and ten Puerto Rican women. Men could become honorary members. Edith W. Hildreth was named president of the local Protestant Temperance League, but there was no overarching body to unify all Leagues of Temperance. Hildreth herself was not even elected by members. It was not until 1918 that the Leagues would hold their first convention and establish the Protestant Insular League of Temperance.

A congressional climate that favored prohibition during a time of war facilitated its inclusion into Article II of the Jones Act on March 2nd, 1917. This occurred despite opposition from colonial officials, such as Governor Authur Yager and Resident Commissioner Luis Muñoz Rivera. The law stipulated that "a year after the approval of this Act and time following, it would be illegal to import, fabricate, sell, give, or exhibit for sale or gifting any drink or drug of intoxicating nature…” After this amendment, the government planned to celebrate the first referendum in July of 1917. Those defending prohibitionist measures were channeling their discontent with the precarious political and economic state within the Island that had allowed a Hispanic regime to be maintained for centuries. Supporting prohibition would symbolically become associated with the social betterment ideals of new American citizens in Puerto Rico.

Within this context, a sector of women from the Puerto Rican elite arose to organize the Women Temperance Societies, despite women being silenced for centuries in their attempts for political participation. These women let their voice be publically heard in the anti-alcohol fight. These women were privy to more education and professional opportunities, and they did not arbitrarily identify themselves with any political parties or religious groups (despite most of them being Catholic). Further, they did not integrate themselves with any of the local Protestant temperance groups already established for organizational purposes.

In this piece, I propose that by forming and defending a separate prohibitionist campaign, these women had the opportunity to strengthen an organizational strategy separate from that of men, who aligned themselves to the masculine Leagues of Temperance. Above all, temperance facilitated a transition from the domestic sphere to the public sphere for women, without distancing themselves too violently from the traditional conception of "feminine decorum" and the cult of domesticity in a markedly male-dominated society.

These groups of women began organizing themselves in March of 1917, once the prohibitionist amendment was incorporated into the Jones Act. By May of 2017, 19 towns were part of these groups. The ones from Ponce and Yauco, two southern municipalities in Puerto Rico, were considered "… strongholds of the redeeming cause of prohibition." They were known as the Women's Temperance Societies, and they created a social protest movement backed by the sectors previously mentioned here, as well as by the Socialist Party founded in 1915, the Teachers Association, and men that organized their own prohibitionist leagues in almost every Puerto Rican town. The Societies grouped women 21 years of age and older who were from well-off sectors of societies, professionals, or wives of such, and counted on this registry of members to have voting rights in the organization.

A faction of the Societies' leadership later channeled the fight for women's suffrage, given that many women who were a part of the prohibitionist movement also identified with the cause for suffrage. By 1908, three working women belonging to the Free Federation of Workers had submitted a formal claim to the Legislature soliciting womens’ right to vote during the Federation's fifth Congress. Likewise, the Socialist Party also advocated for "universal suffrage for men and women" in its platform.

It is important to remember that the Jones Act incorporated Article 35, which, as María de Fátima Barceló Miller explains, "empowered the Legislative Assembly of Puerto Rico to impose restrictions, by sex and other reasons, onto citizens in their right to vote." Thus, that lended itself to the interpretation that if such law bestowed the right to vote upon American citizens older than 21 years of age, without specifying restrictions, women should also be included in that group. Discussions surrounding suffrage would peak in 1919. On August 26, 1920 the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution would become law. American women voted that fall and cast a ballot in their first presidential election.

Ángela Negrón de Vivas propelled the women's suffrage movement in Puerto Rico, establishing the Women's Society of Temperance and presiding over the Women's League of Ponce. Lola Pérez Marchand de Goico joined the Women's League as its vice president, becoming one of the first Puerto Rican women doctors of medicine associated with the suffrage cause. Rosa Báez de Silva (the League's secretary) and Amina Tió de Malaret (an honorary member of the League) were also associated with the suffrage cause. Other suffragists within the Puerto Rican temperance movement include Ana Roque de Duprey from the Committee of Humcao, Trina Padilla de Sanz, "The Daughter of the Caribbean," in Arecibo, Carlota Matienzo in Río Piedras, and Grace de Lugo Viñas in San Juan. Being an all-women's organization and separating themselves from other organizations by gender, The Women's League also divided itself by class. However, women sought professional male counterparts as allies to provide support across a variety of spheres. Some of these male professionals included Francisco del Valle Atiles, Francisco Matanzo, Ramón Negrón Flores, Celedonio Carbonell, and Herminio Rodríguez.

The spokeswomen of the local Women's Societies promoted progressive ideas and encouraged the use of governmental power as an instrument of positive reform and order. They emphasized that the Leagues were a means of adopting anti-crime measures and saving lives. They exposed eugenic arguments over the need to avoid race degeneration due to alcoholism. It was these arguments that opened the door for the Societies' women to participate in public platforms where they could exhibit their intellectual capacities and oratorical power. By articulating a benevolent discourse, these women extended their domestic roles outside of the home and avoided clashing with the strong force of a patriarchal society that doubted their ability to do so. As a long-term strategy, they would not distance themselves fully from their traditional roles. Instead, these women would capitalize upon their traditional roles in the public arena to garner more support for their platform from the masculine sectors of society.

By lending themselves as safeguards of peace in the home, the Leagues directed their anti-alcohol arguments primarily towards laborers and farmers. Both of these sectors exemplified the condition of a class oppressed by alcoholic interests. Concurrently, they represented the values of a traditional society wherein alcohol had been important in everyday life, even in daily nutrition. The Leagues promoted the claims of women who had been victims of fist-time alcohol use by their partners and denounced the unrest caused by drunkard fathers. The Leagues' professional women would adopt these causes with a maternal disposition yet maintain a distance at a social level. However, the militant women who were also part of the Socialist party were not permitted to form Leagues independent of men.

The requests sent to the Ponce Town Hall for celebratory prohibitionist gatherings and social evenings showcased the mobilization of women in leadership. Between May 21 and 23 of 1917, the women had celebrated three activities in the "La Perla" Theater in the municipality of Ponce. These activities consisted of various discourses, music, hymns, voicing complaints, and the recognition of women from Ponce for starting this prohibitionist campaign.

Prohibitionist men encouraged the Leagues women who defended the cause by exalting their roles as mothers, wives, sisters, and "matrons of noble souls" for the service of social good. Prohibitionist men conveniently considered it the League women’s duty to convince other male voters older than 21 years of age to vote for prohibition at a time when the Leagues' women could not do so. On July 16, 1917, the referendum's results were devastating for the anti prohibitionists. The vote in favor of prohibition won 61.5% of the total vote (102,423 in favor of and 64,227 against). By the time the prohibition movement reached the implementation phase, elite women abandoned the prohibitionist cause and focused on the fight for women's suffrage that had already been strengthened through their participation in the Women's Leagues.

An interesting transition occurred in alcohol consumption habits when well-off women began smuggling alcohol into the Island. This occurred without implying that the elite women supporting temperance were a part of it. During the 1920's, alcohol became an expensive good due to Prohibition and thus became a symbol of status. Consuming alcohol was no longer an activity reserved for men, and much less for the poor. Alcohol consumption for women reflected a new lifestyle. It signaled women's new presence in exclusive meeting centers where they could provoke social change with drinks in hand. At the time, it was the Protestant "abstainers" who organized the new Leagues of Temperance. When anti-alcohol discourse generally had been exhausted, temperance was strengthened under a separate Protestant women leadership.

We have seen how the Women's Societies provided an opportunity for women to channel their transition into public participation in a variety of ways. At the height of 1917, women stood out as protagonists in "doing good for the needy," given they routinely engaged in acts of social and religious welfare and participated with the Red Cross. By opening up their domestic roles to social service, women were recognized in public activities without distancing themselves from their traditional gender expectations.

Active participation in charitable and religious causes enabled women to move towards a secular platform that would bring about the opportunity to engage directly with men. Women even began voicing opinions in matters that were considered "masculine," such as the impact of prohibition on the national budget. The temperance discussion allowed other social preoccupations to come to light, such as prostitution, bars, the family unit, social order, and women's suffrage. However, analysis of the feminist elite women solely as a "conservative" movement in local history underestimates the fact that they were the ones with the most presence and public recognition for their strategies. For these women, it was vital to organize themselves within a fight that would bind them together. That is why the temperance movement was such a fruitful path for these women to achieve social impact, extend their agenda to other reforms, and make themselves known and respected in the public sphere. Women's suffrage would not come until 1935 in Puerto Rico, but society's refusal to grant suffrage made them even more combative for the cause in the future.

Mayra Rosario Urrutia, PhD is a full professor in the Department and Graduate Program of History at the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras main campus. Her primary publications are related to crime and transgressions, alcohol prohibition, women temperance organizations, the party politics in Puerto Rico in the 20th Century, US and Puerto Rico relations during Second World War and the post war period, and the impact of influenza pandemic of 1918 in the Island. She is the coauthor of five text books. She offers courses on Theory of History, Methodology, graduate courses, and is in charge of several master and doctoral proposals and dissertations.

She has participated in academic forums in Puerto Rico, Spain, Latin America, Canada, the Caribbean and the United States; in diverse workshops for teachers in the educational system; and on boards of academic journals and also provided other services to academic institutions.

Barceló Miller, María de Fátima. The Struggle for Women's Suffrage, 1896-1935. Social Research Center, 1997.