Rising Stars Reflect on STEM Education

In my 34 years working to develop diverse talent in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics, many have addressed why STEM education is important, especially for girls. A good “one stop shop” is the Women in STEM resource library of The Office of Science and Technology Policy, Executive Office of the President.

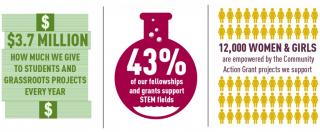

American Association of University Women, a member of the Museum's National Coalition, supports girl's STEM education.

To build on this, meet three collegiate undergraduates who are rising STEM stars – confident, fearless young women already excelling in fields still largely dominated by men. Their contributions and achievements illustrate what is possible when girls can access high quality STEM education.

Kendell Byrd studies computer science and economics at Swarthmore College, has interned as a software engineer at Jawbone, JPMorgan Chase & Co., and Facebook HQ, and was profiled by Women of Silicon Valley.

Drake University neuroscience major Sarah Martin, first runner-up in the Eduzine Global ACE Young Achiever 2016 competition, conducts scientific research in ALS and is building an assistive device that allows people living with the disease to shower more safely.

Yale University computer science major Summer Wu develops apps and wins hackathons, this year the Capital One Summit for Software Engineers Hackathon for her Android app Splitter which uses optical character recognition to parse receipts and split the bill for groups.

The trio reflects on high quality STEM education, what is key for girls, and why it matters.

Wu stresses the importance of well educated, well trained, passionate teachers, up to date facilities and equipment, and opportunities beyond the classroom including learning in real-world settings. The latter is key, Byrd says. In high school, she relished “Inquiry Days,” one day a week where instead of regular classes, students conducted research in university laboratories, interned for a start-up, or designed their own projects.

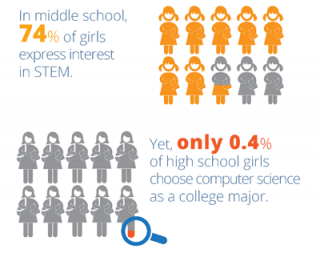

Martin says exposing students to high quality learning experiences may instill a passion that leads to STEM career choices. For girls who already like STEM, this helps them believe they can succeed in these careers, key to reducing gender gaps.

Girls in particular need encouragement at an early age, Wu says, given that subsequent environments are “less than conducive” to helping them achieve their full potential in STEM. She points to a summer program at Northwestern University when she was in middle school. In the mornings, students did labs to introduce new subjects; in the afternoons, they discussed key takeaways and learned new material. “Every day, I felt like my understanding of how the world worked increased tenfold, and I credit that experience for making chemistry my favorite subject when I got to high school years later,” she said.

Empowering young girls with differentiated experiences also opens doors. In the 4th grade, Martin’s teacher let her teach science class sometimes because she was so advanced. “I made my lesson plans and even assigned and graded homework. It helped me become passionate about science at a young age.”

For girls who do not like STEM or who prefer the arts and humanities, Byrd points to how STEM intersects with other areas. With a strong background in STEM, “these girls will be even more well-rounded, open minded, and stronger in their arts and humanities careers.” Martin concurs, noting “interdisciplinary integration” is needed in all kinds of situations and careers. Wu concludes: “STEM teaches students a systematic, logical way of thinking that is beneficial for all of our future leaders, no matter what field they choose to specialize in.”

Author’s Note: These women are alumni of the Illinois Mathematics and Science Academy in Aurora, IL, a public residential institution that enrolls students in grades 10-12 who are talented and interested in STEM. To learn more, visit www.imsa.edu.

Catherine C. Veal is a founding administrator of the Illinois Mathematics and Science Academy where she worked from 1986 to 2015 in various leadership roles.