Raising a Glass to Irish American Women

On the day Ellis Island opened on January 1, 1892, an Irish girl named Annie Moore became the very first person processed through what became the world-famous immigration center. After joining her parents in New York, Annie married Joseph Augustus Schayer, a young German American who worked at the Fulton Fish Market. She bore 11 children, six of whom died before adulthood; she died at age 50 in 1924. She never left New York’s Lower East Side, living the rest of her life in a few square blocks that is today remembered as a notorious immigrant slum. Though Annie would not be remembered if not for being a first, her story nonetheless offers insights into the American experience precisely because she was so very typical.

Ellis Island Immigration Station c. 1905

The Irish, before and after Annie Moore, had a tremendous impact on American history and culture. The U.S. Census Bureau reports that 36.9 million Americans claim Irish roots. The Irish are the second largest heritage reported by Americans after German. But the Irish were unique among all immigrant groups. In immigrating to the United States they accomplished something that no other group even attempted.

THE IRISH SENT MORE DAUGHTERS THAN SONS

By the end of the nineteenth century, single women accounted for 53% of Irish immigrants. The Irish were the only nineteenth or twentieth century immigrant group in which women outnumbered men. Between 1820 and 1860, the Irish constituted over one third of all immigrants to the United States and by the 1840s—at the height of the Potato Famine—they comprised nearly half. After the crisis of the Famine passed and Irish emigration slowed, Irish women continued to migrate in increasing numbers.

Who were these women and why did they come?

Irish women moved to American for the same reasons as men: opportunity and freedom. Young Irish women and girls left behind hard scrabble farms where they worked as long and as hard as men to bring in a crop while also maintaining homes and assisting with children. The Potato Famine devastated the Irish economy. Poor Irish women had few employment opportunities and diminished marriage prospects. So they left Ireland for America.

When they left, they did not try to replicate their rural lives. Instead, they settled in cities where many took jobs as servants or domestic workers. More than 60% worked as maids, cooks, nannies, or housekeepers. Domestic work came with several advantages. Living with wealthy or middle class American families intimately exposed Irish women to American culture, speeding acculturation and assimilation. The greatest advantage was financial. Not only were the wages higher than those for factory workers, as live in help domestics had no housing expenses, which enabled them to save more money.

Women helped women

Strong female networks sustained the immigration flow of Irish women, even during times of economic depression. Women sent money back home to support families but they also paid the passage for their female relatives. Irish women were the only immigrant group to establish immigration chains. They brought over nieces, sisters, cousins, and friends. They were young, under age 24, and unmarried. These women had the freedom to migrate and the desire for independence. Whereas other ethnic groups sent their sons to America, Ireland sent its daughters.

In America, those daughters developed a reputation for independence. They became education advocates, civil rights leaders, and cultural critics. They changed America.

American Irish prioritized education. The Catholic Church in Ireland launched an education initiative in the late 19th century expanding access to educational opportunities. The Irish Catholic Church in American built on that teaching mission, establishing parochial schools throughout the country that educated generations of Irish Americans. And Irish-Catholic sisters founded scores of schools and women’s colleges. In 1900, Irish American girls attended school at higher rates than any other group, including American-born boys. Before coeducation in the 1960s opened American colleges to more women, more American women earned degrees from Catholic women’s colleges than from Protestant or nondenominational institutions. Education aided social and economic mobility for successive generations.

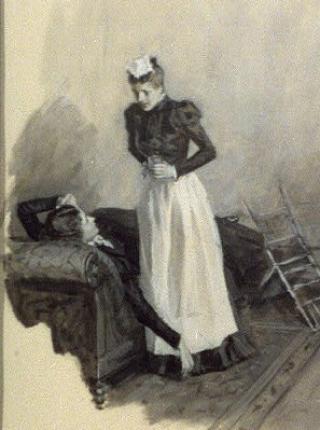

Irish maid, 1898.

Education facilitated Irish American women’s entrance into the workforce. Second generation Irish women entered the professions at higher rates than any other immigrant group, becoming teachers, bookkeepers, typists, journalists, social workers, and nurses. By 1910 Irish American women represented the majority of public elementary school teachers in Providence, Boston, New York, Chicago, and San Francisco. And by 1939, 70% of Chicago’s schoolteachers were Irish American women. Domestic work provided the first generation’s entry point into the American economy. But the second generation turned its back on servitude, preferring the relative autonomy and regular hours found in government and business.

Once in the workplace, Irish women demanded justice and equality. The second generation protested obvious discrimination and were among the first to organize and join labor unions. Though they were underrepresented among manufacturing workers, Irish American women were overrepresented among union leadership. Moreover, they introduced unions to service and professional fields. They organized teachers unions in order to eliminate male and female pay discrepancy.

Laundry Workers Union of New York, 1914.

Irish American women also made their mark through literature and journalism. Advanced education produced a generation of literary women, many of whom became professional journalists and novelists. Their subject matter often addressed women’s social inequities. Crusading journalist Elizabeth Cochrane, known by the pen name Nellie Bly, revealed abuse of the mentally ill in her newspaper expose “Ten Days in a Mad House”. Kate Chopin’s classic novel The Awakening criticized the stultifying confines of traditional American womanhood. Margaret Culkin Banning wrote over 400 articles for the leading women’s magazines of the day addressing taboo subjects like body image, alcoholism, and the difficulties of marriage. Their collective bodies of work demonstrate a commitment to fairness and social justice.

Irish women in America made an impact

The documentary evidence gathered from letters and journals suggests that Irish women found the adventure of their new lives in America as compelling as the economic opportunities. Living and working in the United States offered Irish women opportunities for autonomy and self-sufficiency lacking in the more patriarchal structure of “home”. Once in America, they firmly established themselves as a force with which to be reckoned. Their strong networks, formed by immigration patterns and sustained by shared membership in the Catholic Church, nurtured a culture and pride among Irish American women that continues to this day. During Irish American Heritage Month, let’s toast the strong and determined Irish women who became Americans.

- Diner, Hasia R. Erin’s daughters in America: Irish immigrant women in the nineteenth century. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins university press, 1993.

- Ebest, Sally Barr. “Irish American Women: Forgotten First-Wave Feminists.” Journal of Feminist Scholarship 56, no. 3 (Fall 2012). Accessed March 23, 2016.

- Graham, Ruth. “What American Nuns Built – The Boston Globe.” BostonGlobe.com. February 23, 2013. Accessed March 23, 2016.

- Nolan, Janet. Ourselves alone: female emigration from Ireland, 1885-1920. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1989.