Moving the Women into the Light: An Interview with NWHM Co-Founder Ann E.W. Stone

On Mother’s Day weekend two decades ago, a group of women dedicated themselves to moving Adelaide Johnson’s Portrait Monument to Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony out of the US Capitol’s basement, known as the Crypt, to its rightful place in the Capitol Rotunda.

The statue more commonly known as The Woman Suffrage Statue, memorializes pioneering suffragists, and first arrived at the Capitol on February 10, 1921. On February 15, it was unveiled in a ceremony as a gift from the “women of the Nation…to the People of the United States,” by the National Woman’s Party. The very next day, “the Portrait Monument traveled outdoors, down the Capitol steps, and through the doors into the Crypt” where it remained for nearly 76 years.

The statue’s original journey to the Capitol was complex and controversial, and its move back to the Rotunda was no less so. The Woman Suffrage Statue Campaign was responsible for moving the statue back to its intended and rightful place in the Capitol Rotunda, and sparked the movement that is the National Women’s History Museum today.

NWHM Board Member Ann E.W. Stone and President and CEO Joan Wages were there, and spoke with us about the challenges and triumphs of moving the statue.

How did the Woman Suffrage Statue Campaign start?

Ann Stone: It was 1995, and the National Women’s History Museum’s eventual founder, Karen Staser happened upon the Portrait Monument by accident during one of her visits to the US Capitol building. There was no signage as to who was in the statue, although she thought she recognized Susan B. Anthony, but she was not sure who the other two were.

Later that day, she visited the Sewell-Belmont House, now the Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument, and noticed information about activity around the 75th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote. On the wall, was a poster with a picture of the very same statue she had just seen in the Capitol Crypt. Karen learned a brief history of the statue and how the National Women’s Party wanted to move it back to the Rotunda. But, they had run into all sorts of roadblocks including new Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich.

Debbie Johnson and Ann E.W. Stone

Karen’s husband worked for Senator Ted Stevens from Alaska, and she offered to help by setting up a meeting to see if they could enlist his support. The meeting went better than expected. The women who helped raise Senator Stevens were suffragists. He learned the suffrage songs as a child and would sing them at the slightest provocation. He was excited to help.

To shore up support, Senator Stevens enlisted Senator John Warner from Virginia to help, and the legislative movement began. The Senate voted unanimously to approve the move.

The House of Representatives was more difficult. The first vote went down in defeat due to the objections of three women members because it was a time of budget cuts and they could not justify government funds to move the statue. They did not object to the move, just using public money to do so.

As 1995 drew to a close, the 75th Anniversary would soon be over. Karen and Joan Meacham co-chaired a new effort to move the statue and named it the “Woman Suffrage Statue Campaign.” They knew they could count on Senators Stevens and Warner again, so focused their efforts on the House.

How did the legislation finally pass?

Stone: My neighbor worked at the Sewall-Belmont and gave Karen my name as someone who might be able to help with Congress. She came to my office in Alexandria in early 1996. She explained what happened and how they wanted to try again. This would be the fifth attempt since the 1920s to raise the statue since it had been banished to the Capitol’s basement.

Karen said they had been working with Maryland Representative Connie Morella as one of their conduits to the Speaker. I knew Connie well and called her to see what was holding up the move. The Speaker’s office was under the impression that this was a push by liberals for political reasons. I called the Speaker’s office and gave him the history of the statue, pointed out the women in the statue were all Republicans and said, “So, you have locked three Republican women in the basement.”

The message was received and the negotiations began in earnest again. There were a lot of objections to this particular statue from all sides. Some of the women members of Congress hated it, thought it was ugly, and thought male members of Congress would make fun of them by ridiculing the statue. Some thought other figures should have been in it. Still others wanted a whole new statue.

Discussion went round and round, and finally we stated emphatically that this statue was the one the suffragists gave us. This statue is the one through which all women in America were dishonored when it was shoved in the basement. So this statue had to be the one to come back up into the Rotunda to restore their honor—if only for a few years until a new statue could be commissioned to take its place.

We reached a tentative agreement, and legislation was drafted to move the statue after one year. We agreed to raise private money to pay for the move so no government funds would be required.

The House finally joined with the Senate and passed Concurrent Resolution 216 to authorize the statue’s move.

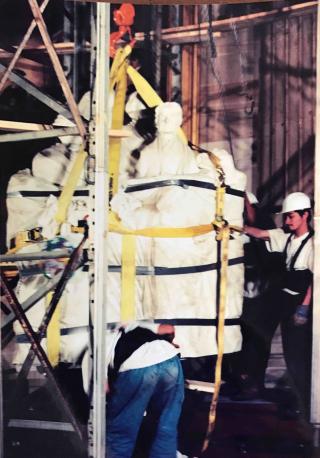

The relocation began on May 10, 1997, the day before Mother’s Day. How did you feel that weekend?

Joan Wages: All of us who worked on the campaign showed up early on Saturday morning—very excited. But the day dragged on because the construction crew could not figure out how to lift the seven tons of marble up onto the Rotunda level. By early evening, they quit for the day. The next morning, we arrived back at the Capitol bright and early before the tourists were allowed in. They had figured out the way to lift it and by mid-morning the statue moved into the Rotunda. Saturday had been rainy and overcast. When the statue came in, the sun broke through and everyone cheered.

While the crew worked, we had pizza delivered. We sat on the Rotunda floor, ate pizza, and drank champagne. One of the Capitol curators was horrified and assured us that had never been allowed before. Since it was almost midnight, she gave us a pass. We also knew that once placed, the statue would never be moved because of its weight and size.

Stone: As the statue was lowered onto its new base, all of us assembled saluted these three courageous, persevering women with champagne.

This year we celebrate the 20th Anniversary of the National Women’s History Museum’s milestone accomplishment as we continue our mission to mainstream women’s history into our culture, our books, our parks, entertainment, and our museums.

Millions of visitors have passed through the Capitol since the statue returned to its rightful place alongside the men who also contributed much to our nation. And millions more will hear and learn about these suffragists battle to secure women the right to vote because of our efforts.

Weber, Sandra. The Woman Suffrage Statue: A History of Adelaide Johnson's Portrait Monument to Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony at the United States Capitol. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc, 2016.