The First Ladies: Dolley Madison

Much more so than her predecessors, Dolley Madison embraced the role of First Lady as we think of it today. In fact, she pretty much created it, setting the bar upon which all later First Ladies have been judged. While Abigail Adams acted as a private adviser to her husband, Dolley was a very public partner to James. In the eulogy he gave at her funeral in 1849, President Zachary Taylor called Dolley “the first lady of the land for half a century.” It was the first time a president’s spouse had been referred to as a “first lady,” although the term did not become an official title until the 1860s when newspapers began using it for Mary Todd Lincoln. When she died, Dolley Madison was the last public figure from America’s founding generation.

Dolley was born to John and Mary Coles Payne, both strict Quakers, on May 20, 1768. She was raised in the Quaker faith, which taught equality between women and men. Dolley took that teaching with her throughout her life, never seeming to act like she was of lesser status because she was a woman. Her parents relocated the Payne family to Philadelphia when Dolley was young and it was in that city in 1790 that she married John Todd. The Todds had two children, John Payne and William. The yellow fever epidemic that swept through Philadelphia in 1793 took the life of John on the same day the infant William died. Though John had made Dolley the executor of his will, her brother-in-law kept everything from her and left her in near-poverty until she took legal action to obtain what was rightfully hers. Because she was a woman, she also had to fight in court to be the guardian of her own surviving son.

By 1794, Mary Coles Payne was widowed and running a boarding house to earn an income. One of her boarders, Aaron Burr, had been persuaded to arrange a meeting between the eligible new widow and his close friend/persuader, James Madison, in May 1794. The two began a courtship, which was not approved by the Society of Friends because there had not been an appropriate mourning period for John and because James was not a Quaker. When Dolley and James married in September 1794, she was excommunicated from the Quaker church. This marked a liberating shift in her life. Taking after her mother, Dolley kept the Todd house in her own name, took on renters, and earned her own, separate income for a period of time after she and James were married. For a brief few years after their marriage, James retired from politics and the two lived peacefully on the Madisons’ plantation in Virginia. When James’ political ally, Thomas Jefferson, became President in 1801, he was convinced to return to politics and serve as Jefferson’s Secretary of State. For the next 16 years, the Madisons would be the most powerful couple in Washington.

Dolley Madison. 1848.

Jefferson, a widower, asked for Dolley’s assistance in entertaining, which worked out well because the Madisons lived with Jefferson in the President’s House (as the White House was then called) for the first year of his first term. Acting as hostess for Jefferson provided her with a great deal of experience in Washington’s political and social scenes before actually becoming First Lady herself. In addition to being Jefferson’s hosting partner throughout his administration, Dolley also helped to raise funds for Lewis and Clark’s exploration of the newly acquired Louisiana Territory. While she did act as Jefferson’s hostess when needed, he did not entertain at the President’s House often and his gatherings were as low key as he could manage to make them. After they moved into their own place a couple blocks away, Washington’s social scene became centered around the Madisons’ home, thanks to Dolley. It is quite possible that Dolley’s social gatherings, to which she invited a bipartisan mix of important political leaders and the social elite, helped her husband win the presidency himself 1808.

Dolley Madison's silk gown

For the occasion of James’ inauguration in 1809, a Navy captain asked Dolley if a formal dinner and dance could be thrown in the couple’s honor. Upon saying yes, Dolley approved the tradition of the inaugural ball that continues to this day. As First Lady, she continued her by then well-known style of entertaining, but on a larger scale. In public, James and Dolley Madison appeared to be virtual opposites. James was quiet, reserved, and also short at a time when a man’s physical prowess correlated with his political power. Dolley, on the other hand, was very outgoing, personable, and significantly taller than her husband. James was not good at leading conversation so he had Dolley sit at the head of the table at dinners so she could direct the night’s topics. She was able to draw out people’s views on certain issues and relay that information back to her husband. James, who was also not good at bridging the gap between opposing political parties, deferred the peacemaking between political foes to Dolley. Once, she got two fighting members of Congress to call off a duel. Unlike his wife, James was not a flashy dresser. After being excommunicated from the Society of Friends, Dolley ditched the very conservative garb worn by Quaker women for the extravagant, but classy, style she became known for. Dolley made a point to dress a certain way that stood out without making her look too much like royalty. She dressed in bright colors, started a new trend with the trademark turbans she wore around her head, and caused a stir with her low-cut empire waist gowns. She was inspired by European fashions of the day, but made them distinctly American and fitting with the republican style government of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Though some critics thought she looked too “queenly,” most newspapers talked about her style as if they were proud she was, through her clothing, showing the American people “something to aspire to as a new nation.” Women across the country seemed to also approve of her style, as many began copying it.

One of the first things Dolley did after her husband took office was redecorate the President’s House, a task considered at the time to be men’s work. She made it a point to have the house look classy but not royal, like her clothing. She also made it a point to purchase all American-made furnishings. While serving as First Lady, Dolley used the limited political power she had as a woman to the fullest extent. Every Wednesday, she hosted “drawing room” gatherings at the house that were much less formal than social gatherings hosted by Martha Washington and Abigail Adams. These drawing rooms were so well attended, they were often referred to as her “squeezes” because so many people crowded into the reception room. Dolley is said to have made an effort to at least shake hands with everyone in attendance. By inviting a diverse crowd of Washington’s most important people and guests to the city, she tried to publicly override the underlying feeling many people had that the new country was on the brink of falling apart. Dolley also held what she called “dove parties,” at which she and the wives of other political figures would discuss current events. As First Lady, she attended debates in Congress and encouraged other women to do the same. She was the first First Lady to be interviewed by a newspaper and the first to use her public role for good. After the War of 1812, she donated $20 and a cow to the Washington City Orphans Asylum, and sewed clothing for the children there. She also promoted the cause in hopes of getting other citizens to help out as well.

Portrait of George Washington saved from the White House during the War of 1812.

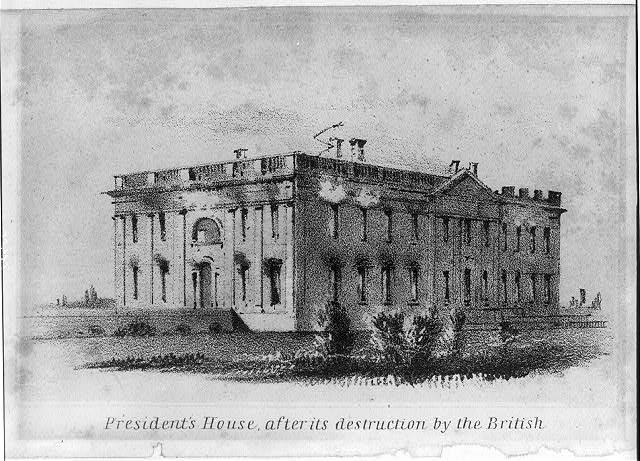

The War of 1812 was the marking event of the Madison administration, and James was becoming less and less favorable in the eyes of many Americans because of his and his administration’s handling of it. Throughout the war, Dolley showed unwavering support for her husband, even giving speeches to boost morale and show support for the war effort. With the American military dwindling, James left Dolley at the President’s House to be with army officers in Bladensburg, Maryland in August 1814. British officers had their sights set on the capital city and they began verbally attacking and making threats to Dolley, not James, as they neared, a sign of the true political power she held. They claimed they were going to eat at her dinner table, bow in her drawing room, take her as a prisoner of war, and parade her through the streets of London. This did not deter Dolley, as she stayed in Washington waiting for James to return in an attempt to show the American people their government would stand strong. As the British advanced, she could hear cannons firing at nearby battles but looking out from atop the President’s House roof, she could only see citizens and soldiers abandoning the city. James had ordered 100 armed soldiers to protect the President’s House. By August 23, all 100 had fled and the city was nearly a ghost town. Dolley was virtually alone with a few slaves and servants. James sent her a message from the battlefield urging her to get out of Washington. She began packing up trunks full of irreplaceable national documents, such as James’ extensive notes on the proceedings of the Continental Congress and the Madison cabinet papers, as well as silverware and red curtains from the President’s House, sending them away and hoping they would be safe. She invited people to her regularly scheduled drawing room on the 24th and ordered for the dinner table to be set, despite the fact that no one accepted her invitation. In a letter written to her sister between Tuesday, August 23 and Wednesday, August 24, 1814, Dolley says a friend, Mr. Carroll, had come to take her away from the city the afternoon of the 24th. She finally agreed to leave, but only after she did what perhaps she is most famous for – saving the Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington. The frame was bolted to the wall and the slaves and servants assisting her did not have the tools or the time to take it off, so Dolley ordered them to break the frame and cut the portrait out. She finished the letter to her sister saying, “I must leave this house, or the retreating army will make me a prisoner in it…When I shall again write you, or where I shall be tomorrow, I cannot tell!” According to a later account by one of the Madisons’ slaves, Dolley grabbed an original copy of the Declaration of Independence on her way out and left for safety in Virginia. About two hours later, the British arrived on the grounds of the President’s House with torches ready to burn it down. Before they set the house ablaze, the officers sat down and tasted Dolley’s drawing room meal. They then moved on to destroy other federal buildings.

The Madisons both returned to Washington quickly after the burning of the city to show the country that their government was still running. They rented a house near where the charred President’s House stood, resisting urgings from members of Congress to move the capital to somewhere safer. Dolley resumed her weekly drawing rooms and other socially political activities. After James’ presidency was over, the couple retired to their Montpelier home in Virginia. Dolley remained the social life of the party, hosting gatherings larger than she ever had as First Lady. When James’ health started to decline, Dolley helped him ready his papers for publication and acted as his secretary on the matter when he could no longer write. After his death, Dolley sold Montpelier due to financial problems and moved back to Washington, where she was treated like a national treasure. Upon hearing about her financial state, people, including at least one former slave, gave her whatever they could. She was invited to all the social events and continued to host her own.

During the Polk administration, people would leave Sarah Polk’s dry parties to go over to Dolley’s. Upon her return to Washington, Congress unanimously voted to give her an honorary seat in the House of Representatives – the only First Lady to be the recipient of such a gesture. They also voted to give her franking privileges so she would not have to pay postage on any letter she mailed for the rest of her life. Just as popular with the American people as she was with those who ran the government, Samuel Morse gave her the opportunity to be the first private citizen to send a telegraph (after himself), which she did, sending her love to a cousin in Baltimore. When Dolley Madison died on July 12, 1849 at age 81, the whole country grieved. The government closed so people could pay their respects at her funeral – the largest state funeral in the country’s history at the time.

"First Lady Biography: Dolley Madison." National First Ladies' Library.

"First Ladies: Influence and Image." C-SPAN.

"The First Ladies at the Smithsonian." Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

Harbster, Jennifer. "First Ladies of Fashion." Library of Congress, January 18, 2013.

O'Brien, Cormac. Secret Lives of the First Ladies: What Your Teachers Never Told You about the Women of the White House. Philadelphia: Quirk Books, 2009.

Roberts, John B. Rating the First Ladies: The Women Who Influenced the Presidency. New York: Citadel Press, 2003.