SPARS: Coast Guard Women in WWII

Untitled(circa 1942-1946) by United States Coast Guard | National Women's History Museum

Untitled(circa 1942-1946) by United States Coast Guard | National Women's History Museum

SPARS: COAST GUARD WOMEN IN WWII

Untitled - circa 1942-1946, United States Coast Guard | National Women’s History Museum

Untitled - circa 1942-1946, United States Coast Guard | National Women’s History Museum

Women and the Coast Guard at War

"Where we are needed, there we serve — we are the girls of the Women's Reserve."

- Unknown Source

SPARs Visit Combat Vessel circa 1942-1946

SPARs Visit Combat Vessel circa 1942-1946United States Coast Guard | National Women’s History Museum

“There were those who could hardly wait to be a part of the service, and there was at least one who admittedly stepped into a recruiting office to get out of the rain and who got into the Coast Guard as result. The reason that always left the casual inquirer wishing he hadn't asked was, 'My husband (brother, fiancé) was killed at Pearl Harbor...the Java Sea...Salerno...'”—An excerpt from Three Years Behind the MastBy 1942, WWII was well underway. Though the United States Coast Guard began employing women as civilian clerical workers a year earlier, the service sought to free up men for active duty.

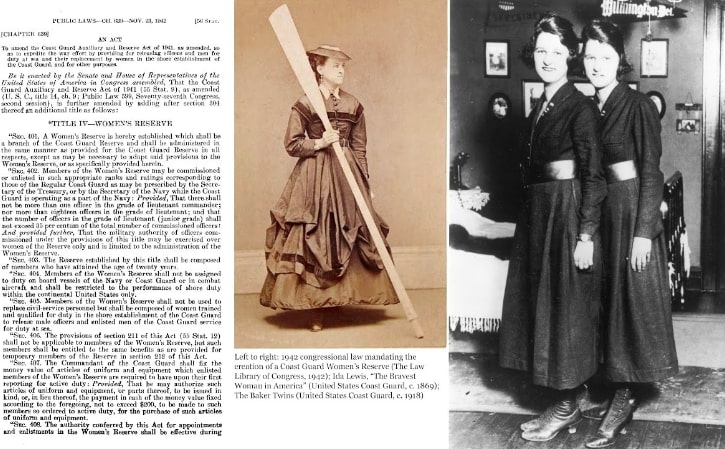

Image Collage: A Brief Early History of Women in the Coast Guard 1869-1942

Image Collage: A Brief Early History of Women in the Coast Guard 1869-1942United States Coast Guard; United States Congress | National Women’s History Museum

Based on an act of Congress signed into law by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt on November 23, 1942, the Coast Guard was legally designated to begin enlisting women.From its early iteration as a lifesaving organization in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Coast Guard saw many women, like Ida Lewis, serve as rescue boat operators for stranded sailors and keepers of lighthouse lamps. In 1918, twin sisters Lucille and Genevieve Baker became the first women to serve in the Coast Guard in an official capacity during WWI. They transferred from the Naval Reserve to undertake clerical duties as Yeomen but were more commonly referred to as Yeomenettes, a sign that while their services were welcomed, their presence as equals was not. Though SPARs were not immune to the military's entrenched sexism, their work was deemed crucial, and was respected as such.

Image Collage: Captain Dorothy C. Stratton and the First SPARs circa 1942-1946

Image Collage: Captain Dorothy C. Stratton and the First SPARs circa 1942-1946United States Coast Guard | National Women’s History Museum

“We shall always think of the Coast Guard with loyalty and affection.” —Dorothy Stratton. Dorothy Stratton, who was the first dean of women's studies at Purdue University in 1933, left her scholarly post in 1942 to become a lieutenant in the Navy's WAVEs. She was subsequently recruited into the Coast Guard, becoming its first female officer, and taking on the role of director of the women's reserve.Initially named the WORCOGS, for Women's Reserve of the Coast Guard, this unwieldy name was superseded by Stratton's own creation, SPARs, a play on the Coast Guard motto, Semper Paratus, and its meaning, always ready. It was duly clever as a spar is a supporting beam on a ship and symbolized the key supporting role that the Women's Reserve would play for the service.Stratton and additional women directors oversaw the enlistment of 10,000 women and the commission of 1,000 female officers, and Stratton was later awarded the Legion of Merit for her efforts.

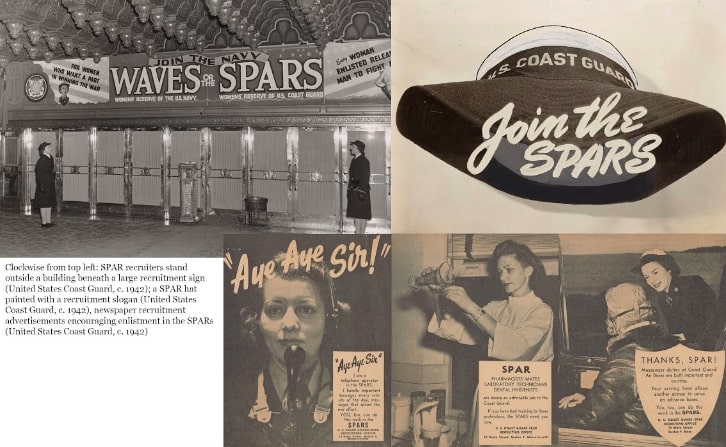

Image Collage: SPAR recruiters; a SPAR hat with a slogan, and recruitment newspaper ads circa 1942-1946

Image Collage: SPAR recruiters; a SPAR hat with a slogan, and recruitment newspaper ads circa 1942-1946United States Coast Guard | National Women’s History Museum

The first SPAR recruits, a total of 34 women, were transferred from the Navy's WAVE program, and joint WAVE/SPAR recruitment offices yielded fewer SPAR enlistees. The Coast Guard set up its own recruitment offices to increase enlistment numbers.As efforts grew, Coast Guard recruitment offices were opened in 27 states, with multiple offices in locales such as California, Florida, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Texas, ensuring that the applicant pool would be a geographically-diverse one.

Untitled circa 1942-1946

Untitled circa 1942-1946United States Coast Guard | National Women’s History Museum

Visiting a SPAR recruitment office in Seattle, Washington (United States Coast Guard, c. 1942)

Image Collage: SPAR recruitment window display and SPAR recruitment posters.circa 1942-1946

Image Collage: SPAR recruitment window display and SPAR recruitment posters.circa 1942-1946United States Coast Guard | National Women’s History Museum

The initial wave of recruitment targeted younger white women. Recruitment posters and films often reflected gendered expectations of women and established the Coast Guard's aesthetic ideals for how these women should look and act. The overarching theme was one of patriotism and duty to one's country.

Coast Guard SPARs circa 1942-1946

United States Coast Guard | National Women’s History Museum

The Coast Guard made multiple SPAR recruitment films, including this one from circa 1942.

Future SPAR Officers Reviewed circa 1942-1946

Future SPAR Officers Reviewed circa 1942-1946United States Coast Guard | National Women’s History Museum

What Makes a SPAR?

"We send his mail rations, whatever his crew may need, check his radio, send his monthly dough, pack his 'chute and chart his speed, we're cam'ra-men and craftsmen, we drive a truck or a jeep, we're pastry cooks and draftsmen, on tower watch we never fall asleep—true blue and always ready, and standing behind the Tars! Yes! From coast to coast, where we're needed most, you'll always find the SPARs!" —Lyrics from "True Blue and Always Ready," one of many morale-boosting songs in the SPAR Song Book

Image Collage: SPAR uniform and enlistment requirements.circa 1942-1946

Image Collage: SPAR uniform and enlistment requirements.circa 1942-1946United States Coast Guard | National Women’s History Museum Left to right: SPAR winter uniform (United States Coast Guard, c. 1942); SPAR pamphlet listing recruitment qualifications (United States Coast Guard, c. 1943)

Women who were interested in becoming SPARs had to meet specific enlistment criteria. They had to be at least eighteen but no older than thirty-six years of age, a minimum of 5 feet tall, and weigh no less than 95 pounds. Though they could be married, their spouses could not be Coast Guardsmen. Their eyesight had to be easily correctible with glasses if not 20/20, their hearing reliable up to fifteen feet, and their teeth in good condition. The completion of at least two years of high school or a junior college degree was the final requirement. Women interested in commissions as officers were subject to the same basic requirements.

Additionally, they had to have a bachelor's degree or four years of comparable work experience. They could be up to forty-nine years old when seeking a commission.Overall, potential SPAR women were promised room and board as well as fashionable uniforms made by the haute couture design label Mainbocher. Pay was equal to what their male counterparts made.Left to right: SPAR winter uniform (United States Coast Guard, c. 1942); SPAR pamphlet listing recruitment qualifications (United States Coast Guard, c. 1943)

Image Collage: Palm Beach Training Center circa 1940-1946

Image Collage: Palm Beach Training Center circa 1940-1946United States Coast Guard; The Tichnor Brothers | National Women’s History Museum Clockwise from top left: SPAR recruitment display featuring a large image of the Palm Beach Training Center (United States Coast Guard, c. 1943); enlisted SPARs train in front of the repurposed Biltmore Hotel (United States Coast Guard, c. 1943); a postcard of the Biltmore Hotel before its conversion to a SPAR training facility (The Tichnor Brothers, c. 1940)

Though initial SPAR training was carried out at A&M University in Stillwater, Oklahoma, in June of 1943, the Palm Beach Biltmore Hotel was retrofitted to serve as the central SPAR indoctrination center for enlisted recruits. The first SPAR officers, who had transferred from the Navy's WAVEs unit, were trained at the Naval Reserve Midshipman School in Northampton, Massachusetts. When officer training opened to enlisted women, these SPARs attended the Coast Guard Academy in New London, Connecticut, the first women of the service branches ever to do so.

Image Collage: Black Women Can Serve circa 1944-1946

Image Collage: Black Women Can Serve circa 1944-1946United States Coast Guard | National Women’s History Museum Left to right: Enlisted SPARs Olivia Hooker and Aileen Cooke pose on a ship's ladder in a photograph that includes the photographer's penciled in crop marks (United States Coast Guard, c. 1944); SPARs D. Winifred Byrd and Julia Mosley pose in front of a SPAR recruitment poster (United States Coast Guard, c. 1944)

“It’s not about you or me; it’s about what we can give to this world.”—Olivia Hooker.

In October of 1944, the Coast Guard opened enlistment to black women, further widening opportunities for women to serve their country.

The first black woman to enlist was Olivia Hooker, who signed up for the Coast Guard after first being rejected by the Navy WAVEs due to her race. Though both branches claimed racial equality, the Coast Guard moved faster to implement its policy.Hooker, who was a survivor of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, felt that not enough black women were taking advantage of the new policy and felt compelled to enlist. A total of five black SPARs, including Yvonne Cumberbatch, D. Winifred Byrd, Julia Mosley, Aileen Cooke in addition to Hooker, would serve the Coast Guard as enlisted members during WWII.Left to right: Enlisted SPARs Olivia Hooker and Aileen Cooke pose on a ship's ladder in a photograph that includes the photographer's penciled in crop marks (United States Coast Guard, c. 1944); SPARs D. Winifred Byrd and Julia Mosley pose in front of a SPAR recruitment poster (United States Coast Guard, c. 1944)

Image Collage: Florence Finch circa 1945; 2016

Image Collage: Florence Finch circa 1945; 2016United States Coast Guard | National Women’s History Museum

“I felt very humble because my activities in the war effort were trivial compared with those of people who gave their lives for their country.”—Florence FinchThe SPARs attracted many other amazing women, though none as brave as Florence Finch. Born in the Philippines, Finch's father was American, and her mother was Filipina. She met and married a navy service member while working for Major E. Carl Engelhart's Army intelligence team. When her husband was killed by Japanese soldiers, Finch began helping resistance fighters and American prisoners of war in an effort to avenge his death, until she herself was captured, tortured and imprisoned.After her rescue by American forces in 1945, Finch traveled to be with family in Buffalo, NY, before joining the SPARs that summer.Though her time in the service was brief, she worked in the office of the Coast Guard League in Washington, DC., and left the service with the rank of Seaman Second Class when the SPARs were demobilized in 1947. Finch was the first Filipina-American to serve in the SPARs and was the first woman to receive the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Ribbon for her heroism in the Philippines. She was additionally honored with the Medal of Freedom in 1947.

Two SPARs Under Chute Power circa 1942-1946

Two SPARs Under Chute Power circa 1942-1946United States Coast Guard | National Women’s History Museum

Women's War Work

"Vital jobs done by women so that men may fight." — Coast Guard SPARs recruitment film

Image Collage: SPAR Rates circa 1942-1946

Image Collage: SPAR Rates circa 1942-1946United States Coast Guard | National Women’s History Museum

The majority of SPARs entered the rate, or occupational specialty, of Stenographer or Typist, which saw them doing clerical duties in offices around the US, with a majority stationed at Coast Guard Headquarters in Washington, DC.

A total of 13 rates were open to the SPARs, some of which included:

Pharmacists' Mate

Cook and Baker

Yeoman

Photographers' Mate

Driver

Storekeeper

Radioman

Image Collage: SPAR Rates Continued circa 1942-1946

Image Collage: SPAR Rates Continued circa 1942-1946United States Coast Guard | National Women’s History Museum Left to right: SPAR air crew members at the United States Coast Guard Air Station in San Diego, California (United States Coast Guard, c. 1942); SPAR C.J. Crosby trains as a Radio Technician (United States Coast Guard, c. 1942)

Unlike the Yeomenettes in the First World War, SPARs retained the same job titles attributed to their male colleagues. For example, female radio operators were called radiomen. An anonymous SPAR cadet recounted that “...to make matters even more confusing, when we're not referring to the SPAR officers by name we address them as "Sir'' (it's a man's war, I guess).”Though this conduct starkly highlighted the realm of the military as being a man's one, it also became the lens through which SPARs were seen—as service members equal in rate and pay to the men whom they had replaced.

Image Collage: SPAR Parachute Riggers circa 1942-1946

Image Collage: SPAR Parachute Riggers circa 1942-1946United States Coast Guard | National Women’s History Museum

Two of the most essential rates affecting men on the front lines were the Parachute Rigger, who tested and packed parachutes, and the Link Trainer Instructor, who ran the Link Trainer or flight simulators used to train new pilots. Both rates were initially allotted 18 enlisted women, small numbers reflecting the seriousness of the work involved.Parachute Riggers were expected to have strong attention to detail as mistakes in assembling the parachutes could mean death for men flying on the front lines. Additionally, they would repair damaged parachutes and aviation fabric that covered the wings of planes. SPARs like Helen Laukzemis and Doris Priest carried out these crucial duties as Parachute Riggers in San Diego, California. Collage: SPAR Parachute Riggers Doris Priest and Helen Laukzemis test and pack parachutes before handing them off to Coast Guard pilots (United States Coast Guard, c. 1942)

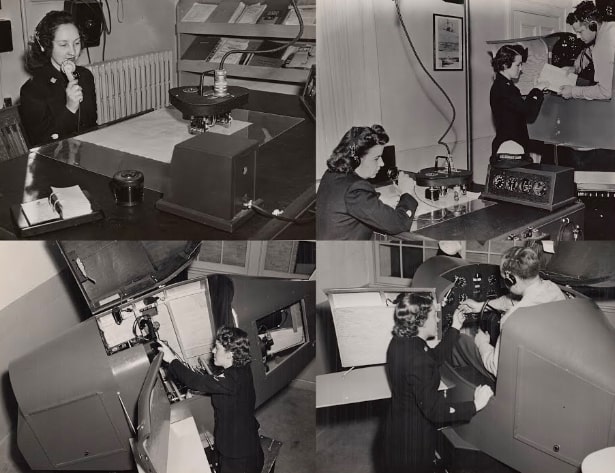

Image Collage: SPAR Link Trainer Instructors circa 1942-1946

Image Collage: SPAR Link Trainer Instructors circa 1942-1946United States Coast Guard | National Women’s History Museum Left to right: Radioman Elfie Larkin and Radio Technician Selma Hoffer. A small and select group of women in these rates served at LORAN stations in places like Chatham, Massachusetts (United States Coast Guard, c. 1942); LORAN tower station on Sand Island in Johnston Atoll provides a visual example of the LORAN tower equipment (Unknown Creator, 1963)

Similarly, the Link Trainer Instructors required a nuanced understanding of the flight simulator equipment and their protocols to impart adequate flight skills to the men in their charge who would soon be heading into real cockpits. SPARs like Dorothy Stellhorn ran the flight simulators as a Link Trainer Instructor at a Coast Guard Air Station in Elizabeth City, North Carolina.

Image Collage: LORAN Station circa 1942-1963

Image Collage: LORAN Station circa 1942-1963United States Coast Guard; Unknown | National Women’s History Museum

In 1943, a group of SPAR women was chosen to take over a LORAN station in Chatham, Massachusetts. Short for long-range navigation, LORAN was a navigation system made possible through the use of low-frequency radio waves, which allowed passing Allied ships to geolocate themselves accurately. This burgeoning technology was to be kept secret, and the eleven women who were chosen to operate the station could not speak about their work to anyone. Under the guidance of Lieutenant JG Vera Hamerschlag, the Chatham LORAN Station's Unit 21 was the only all-female military unit in the world.Unit 21 made Coast Guard history when it was ruled that its enlisted SPARs could give orders to male seamen on passing ships as long as their own commanding officers were male. This rule effectively altered the dynamic of women's roles and power in the military. SPAR Radiomen, like Elfie Larkin, and Radio Technicians, like Selma Hoffer, held the rates deemed most applicable to the mission.Left to right: Radioman Elfie Larkin and Radio Technician Selma Hoffer. A small and select group of women in these rates served at LORAN stations in places like Chatham, Massachusetts (United States Coast Guard, c. 1942); LORAN tower station on Sand Island in Johnston Atoll provides a visual example of the LORAN tower equipment (Unknown Creator, 1963)

Image Collage: Morale and Memories circa 1942-1946

Image Collage: Morale and Memories circa 1942-1946United States Coast Guard; Unknown | National Women’s History Museum Left to right: Spar Song Book (United States Coast Guard, c. 1942); Three Years Behind the Mast (United States Coast Guard, 1946)

During the war, SPAR publications served to keep the women focused on their work and their energy and patriotism high. Like in all military branches during WWII, maintaining morale was an essential aspect of daily life.With songs like “The Girl of the Year is a SPAR” and “Women of the Sea,” the SPAR Song Book provided lyrics and memorable music for women to sing and was given to both cadets and enlisted recruits alike. These songs could be memorized and sung anytime a rise in spirits was needed.With news of the imminent demobilization of the women's reserve, a few women wrote a book to illuminate what life was like for their ilk in the Coast Guard and to keep these stories from being forgotten.In Three Years Behind the Mast, a title alluding to Richard Henry Dana Jr's 1840 sea-faring novel, Two Years Before the Mast, authors and service members Mary C. Lyne and Kay Arthur recounted the experiences of their sister SPARs with the hopes of serving as a written record of their three years of service.The book traces a SPAR's life from enlistment to training school to filling her rate on the job and includes jargon utilized in the service in addition to a history of the Coast Guard in conflict.Left to right: Spar Song Book (United States Coast Guard, c. 1942); Three Years Behind the Mast (United States Coast Guard, 1946)

Untitled circa 1942-1946

United States Coast Guard | National Women’s History Museum

Untitled circa 1942-1946

United States Coast Guard | National Women’s History Museum

And Then the War Was Over

"We were taking away many intangible things that should be of value to us for the rest of our lives—increased tolerance, a new sense of self-confidence, a better idea of how to live and work with all kinds of people, a keener recognition of our responsibility as world citizens." — Excerpt from Three Years Behind the Mast

Image Collage: Women's History in the Coast Guard After the War 1977-2006

Image Collage: Women's History in the Coast Guard After the War 1977-2006United States Coast Guard | National Women’s History Museum Clockwise from top left: The first Coast Guard women cleared for sea duty (United States Coast Guard, 1977); Personnel portrait of Vice Commandant Vivien S. Crea (United States Coast Guard, c. 2006); Lieutenant JG Jeanine McIntosh, the first black woman pilot in the Coast Guard (United States Coast Guard, 2006)

In 1947, the SPARs were disbanded as the Coast Guard prepared for the return of its male service members. Women like Olivia Hooker, who were working in service separation offices, wrote their own discharge papers.

In late November of 1949, women were again allowed to join the Coast Guard as SPARs. In 1950, they were cleared for active duty work. Following this service reinstatement, women continued to make advancements with each decade of their involvement.

The Women's Reserve of the Coast Guard was officially dissolved in 1973, and women were integrated into one unified Coast Guard, making them equals with their male cohort. In 1977, the first group of women were cleared for sea duty.

In 2006, Vivien S. Crea became the first woman to serve in the Coast Guard's second-highest role as Vice Commandant. That same year, Jeanine McIntosh became the first black woman pilot to fly for the Coast Guard.

Today, women comprise nearly 15 percent of the Coast Guard's active-duty force, and they serve in almost all available rates.

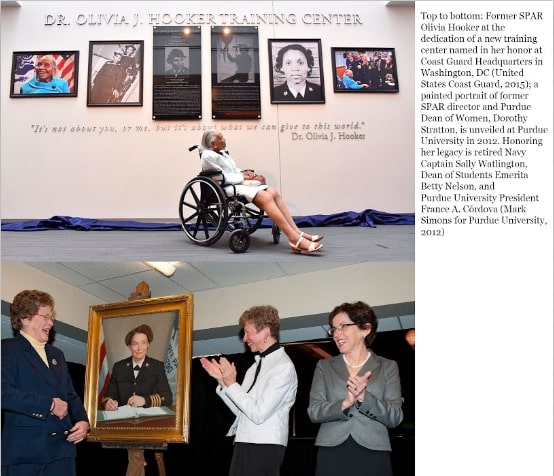

Image Collage: Honoring Trailblazers 2012-2015

Image Collage: Honoring Trailblazers 2012-2015United States Coast Guard | National Women’s History Museum

The Coast Guard's women trailblazers are valued participants of the branch's collective history and women's history as a whole.

In 2010, a Coast Guard cutter was named after Dorothy Stratton. During Women's History Month in 2012, Purdue University Library unveiled a portrait of Stratton in recognition of her work as Women's Dean of the school in addition to her service to the country as Director of the Coast Guard SPARs.

A Coast Guard mess hall in Staten Island and a training building were named in honor of Olivia Hooker in 2015.

In 2019, it was announced that Fast Response Cutter 57 would be named in honor of Florence Finch, and a book recounting her incredible life story will be published in June of 2020.

Women in the Coast Guard 2016

Petty Officer 3rd Class Lora Ratliff for the United States Coast Guard | National Women’s History Museum

It was the participation and service of the SPARs during WWII which paved the way forward for women in the Coast Guard and shattered any preconceptions regarding women's potential and ability to serve their country. While they were not explicitly on the front lines like women from other branches, their efforts in freeing Coast Guard men to join the fray ultimately aided the Allies' success and proved that women were fit for any job and occupation, resulting in more women entering the general workforce in the decades to come.Women in the Coast Guard continue to serve their country in meaningful ways. Their presence reflects their own dedication to service and patriotism, and is forged from the spirit and tenacity of the SPARs during WWII.

Credits

Written and curated by Kate M. Fogle

Photographs and documents were sourced from the following repositories and organizations:

Central Connecticut State University, Elihu Burritt Library Veteran’s History Project, Jean Chittenden Collection.

The Law Library of Congress, Statues at Large for the 77th Congress.

The Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division.

The LibrayThing online book database.

Northwestern University Library WWII Poster Collection.

Purdue University, Purdue News Service online newspaper.

Smithsonian Institution Archives, for The National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian, Pacific Ocean Biological Survey Program records, RU 000245.

The University of North Carolina Greensboro, the Betty H. Carter Women Veterans Historical Project, Women Veterans General Printed Materials and Video Recordings Collection WV0002.

The United States National Archives and Records Administration, Still Picture holdings, Records of the United States Coast Guard RG 26.

The United States Coast Guard historical records holdings.

Selected bibliography:

Facts About SPARs. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Coast Guard, 1943.

Harris, Mary Virginia. Guide Right, a Handbook of Etiquette and Customs for Members of the Womens Reserve of the United States Naval Reserve and the United States Coast Guard Reserve. New York: Macmillan Co., 1944.

Lyne, Mary C., and Kay Arthur. Three Years behind the Mast, the Story of the United States Coast Guard SPARS. Washington, 1946.

The Coast Guard at War Women's Reserve. Washington, DC: U.S. Coast Guard, 1946.

Tilley, John A. A History of Women in the Coast Guard. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Coast Guard Historians Office, 1996.

U.S. Coast Guard Bulletin. Vol. 1-2. Washington, DC: U.S. Coast Guard, 1939.

Very special thanks to Donna Vojvodich and William H. Thiesen.