Parading for Progress

Women Marching in Suffragette Parade, Washington, DC/ National Archives and Records Administration (Mar 3, 1913)

Women Marching in Suffragette Parade, Washington, DC/ National Archives and Records Administration (Mar 3, 1913)by U.S. Information Agency

National Women’s History Museum

Woman Suffrage Parade/Library of Congress (1914)

Woman Suffrage Parade/Library of Congress (1914)by Harris & Ewing, photographer

National Women’s History Museum

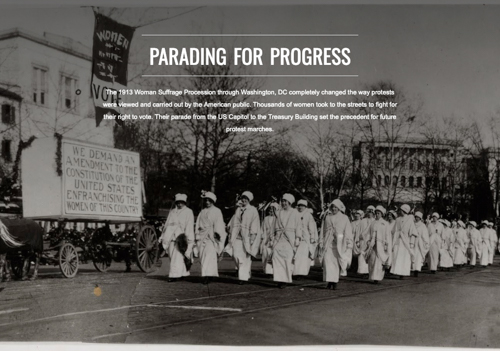

The 1913 Women's Suffrage Parade in Washington, DC, unprecedented in both its scale and its tactics, was a major turning point for the woman suffrage movement in the United States. Suffrage leader Alice Paul, who was recently elected head of the National American Woman Suffrage Association’s Congressional Committee, devised the idea for a large-scale public demonstration. Paul, who had spent time in England, witnessed the more militant tactics that the British suffragettes used to draw attention to their cause.

Suffragette parade, Washington, D.C., on March 3, 1913 LOC

Suffragette parade, Washington, D.C., on March 3, 1913 LOC by Library of Congress

National Women’s History Museum

Applying what she had learned in England, Paul decided a massive parade, perfectly timed with president-elect Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration, would capitalize on the thousands of people gathered in the city.

Our Roll of Honor. Listing women and men who signed the Declaration of Sentiments

Our Roll of Honor. Listing women and men who signed the Declaration of SentimentsNational Women’s History Museum

From Seneca to Washington

During the mid-1800s, female abolitionists began drawing parallels between the condition of the enslaved population and their own condition as prisoners within a patriarchal society. Drawing on this sentiment, women’s rights activists, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, organized a convention in Seneca Falls, New York in 1848, during which they advocated for female suffrage. The Seneca Falls Convention is recognized as the beginning of the Woman Suffrage Movement in the United States.

Handbill, "Twelve Reasons Why Women Should Vote"

Handbill, "Twelve Reasons Why Women Should Vote"by National Woman Suffrage Publishing Co., Inc.

National Women’s History Museum

After the Seneca Falls Convention, suffragists employed numerous strategies to gain support for their cause. Suffrage organizations distributed newspapers and handouts explaining how female enfranchisement would benefit society.

Woman's Sphere Suffrage Cartoon

Woman's Sphere Suffrage CartoonNational Women’s History Museum

Not all women, however, supported the Suffrage Movement. Some considered politics masculine and thought women should stick to more feminine domestic roles.

Woman Suffrage Postcard/National Museum of American History

Woman Suffrage Postcard/National Museum of American Historyby Votes-For-Women Publishing Company

National Women’s History Museum

In response, suffragists argued that the home was part of the larger community, so it was their duty to participate in politics.

Suffragists Mrs. Stanley McCormick and Mrs. Charles Parker, April 22, 1913 LOC

Suffragists Mrs. Stanley McCormick and Mrs. Charles Parker, April 22, 1913 LOCNational Women’s History Museum

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony founded the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) first in 1869. The pair believed that instead of supporting the 15th Amendment as it was, women’s rights activists should fight for women to be included as well. The NWSA wanted a constitutional amendment to secure the vote for women, but it also supported a variety of reforms that aimed to make women equal members of society.

Suffragist Margaret Foley distributing the Woman's Journal and Suffrage News

Suffragist Margaret Foley distributing the Woman's Journal and Suffrage NewsNational Women’s History Museum

The second national suffrage organization established in 1869 was the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Unlike the rival NWSA, AWSA supported the 15th Amendment that granted African American men the right to vote.

5 female Negro officers of Women's League, Newport, R.I.

5 female Negro officers of Women's League, Newport, R.I.National Women’s History Museum

Diversity and Division

Despite the movement’s continuous growth after the convention, not all women were, or felt, welcomed in it. The mostly white movement often discriminated against black women working toward the same goal, and while the AWSA supported the 15th Amendment granting black men the vote, the NWSA did not because it neglected women. In 1890, however, both organizations merged to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), which sought the vote for all American women.

Banner with motto of Oklahoma Federation of Colored Women's Clubs

Banner with motto of Oklahoma Federation of Colored Women's Clubsby Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

National Women’s History Museum

In the 1880s, black reformers began organizing their own groups. In 1896, they founded the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), which became the largest federation of local black women’s clubs. Their motto was "Lifting as We Climb." They advocated for women’s rights as well as to “uplift” and improve the status of African Americans. Even though black men officially won the right to vote in 1870, impossible literacy tests, high poll taxes, and grandfather clauses prevented many of them from casting their ballots.

Mary Church Terrell (1879 - 1900)

Mary Church Terrell (1879 - 1900)by Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

National Women’s History Museum

In spite of the discrimination against them, some women of color became prominent in the suffrage movement, such as Mary Church Terrell, president of the NACW, and Adelina Otero-Warren, who played a major role in New Mexico’s ratification of the 19th Amendment.

Horse drawn float declares National American Wo... (1914)

Horse drawn float declares National American Wo... (1914)by Edmonston, Washington, D.C. (Photographer)

National Women’s History Museum

In 1890 the NWSA and the AWSA united to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) combining their efforts to work towards suffrage.

Ohio Next

Ohio NextNational Women’s History Museum

For decades, suffragists worked hard to earn that right. Constitutional Amendments for woman suffrage were proposed to Congress in 1869, and every year between 1878 and 1920. In the 1890s, NAWSA developed a “state-by-state” strategy, earning women in Wyoming, Utah, Idaho, and Colorado the vote by 1896. Little progress was made between 1896 and 1913, until the march on Washington galvanized the Woman Suffrage Movement and helped lead to the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920.

Alice Paul, half-length portrait, seated, facin... (1912 - 1920)

Alice Paul, half-length portrait, seated, facin... (1912 - 1920)by Library of Congress

National Women’s History Museum

Planning a Parade

Parade organizers strategically selected March 3, 1913 for the march. Woodrow Wilson was to be inaugurated as the new President the following day, and national press was in town and idle awaiting the inaugural festivities.

Official program - Woman suffrage procession, W... (Mar 3, 1913)

Official program - Woman suffrage procession, W... (Mar 3, 1913)by Benjamin M. Dale

National Women’s History Museum

City officials tried to route the parade down 16th Street, away from the city’s core. Paul insisted that it march down Pennsylvania Avenue, deliberately following the same route that the inaugural parade would take the next day. The contrast between the two parades would prove striking. Reporters flocked to the suffrage parade, leaving Wilson to arrive at the train station unheralded.

Tableaux, Treasury Wash., D.C. (Suff. Pageant) LOC (Mar 3, 1913)

National Women’s History Museum

Tableaux, Treasury Wash., D.C. (Suff. Pageant) LOC (Mar 3, 1913)

National Women’s History Museum

Pageantry as Protest

When Paul began to organize a national suffrage parade, a key component of her plan was to channel media attention toward women’s voting rights. Paul had first-hand experience with British suffragettes’ use of pageantry and knew that New York suffragists had staged spectacular parades down Fifth Avenue in the prior three years. These savvy women knew that street spectacle drew attention to their cause.

Inez Milholland Boissevain, wearing white cape,... (1913)

Inez Milholland Boissevain, wearing white cape,... (1913)by Library of Congress

National Women’s History Museum

The parade was choreographed to be highly photogenic. It was led by human rights lawyer Inez Milholland, astride a white horse.

Suffrage march line--How thousands of women par... (Mar 4, 1913)

Suffrage march line--How thousands of women par... (Mar 4, 1913)by Winsor McCay

National Women’s History Museum

The procession included nine bands, four mounted brigades, more than twenty floats, and around eight thousand marchers. The first contingent, dressed in national costume, represented countries whose governments had enfranchised women.

"Home Makers", Suffrage Parade LOC (Mar 1913)

"Home Makers", Suffrage Parade LOC (Mar 1913)by Bain News Service

National Women’s History Museum

Subsequent groups showcased women by profession, including university women, homemakers, librarians, and nurses. All wore symbolic garb.

Ida B. Wells (1891)

Ida B. Wells (1891)by Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

National Women’s History Museum

Women from all over the United States and abroad traveled to Washington, DC to participate in the march. Paul, working with Mary Church Terrell, allowed African American women to participate, but they had to march in the back of the parade. Prominent civil rights activist and suffragist, Ida B. Wells-Barnett didn't agree with the decision. While she started in the back, she ran to the front once the parade began to join the women in her state's delegation.

Crowd breaking parade up at 9th St., Mch [i.e. ... (Mar 3, 1913)

Crowd breaking parade up at 9th St., Mch [i.e. ... (Mar 3, 1913)by Library of Congress

National Women’s History Museum

The parade’s drama was heightened by the crowd’s crass behavior. Marchers were subjected to insults and physical attacks by many of the half million, largely male, spectators. Police stood idly by while the women were assaulted. The press captured dramatic images of the event and distributed them to newspaper readers across the country.

Eventually, the procession made it to its final destination: the steps of the Treasury Building. There an allegorical tableaux was performed on the steps of the building.

[Hedwig Reicher as Columbia] in Suffrage Parade/Library of Congress

[Hedwig Reicher as Columbia] in Suffrage Parade/Library of Congressby Bain News Service

National Women’s History Museum

While women for centuries have been figures of allegory, often cast in the role of the muse, the tableaux challenged these notions of femininity.

Woman Suffrage Postcard (1913)

Woman Suffrage Postcard (1913)National Women’s History Museum

Women were dressed in classical attire, stressing grace and beauty, while also arguing for their rights as women.

[Front page of the "Woman's journal and suffrag... (Mar 8, 1913)

[Front page of the "Woman's journal and suffrag... (Mar 8, 1913)by Library of Congress

National Women’s History Museum

From Sidelines to Headlines

Despite the chaos and violence that initially ensued during the parade, Paul declared the event a success. The parade made national headlines and once again captured the public’s interest in the suffrage movement. The parade and the crowd’s behavior drew attention to the suffragists’ cause. Readers were appalled to learn of the attacks and the police inaction. Even those who opposed votes for women acknowledged that, as citizens, the women had the right to peacefully assemble. That right had been abridged.

Pickets arrested at White House for woman suffr... (1917)

Pickets arrested at White House for woman suffr... (1917)by Library of Congress

National Women’s History Museum

The United States Senate held hearings to investigate the police response, eventually leading to the chief’s resignation. The hearings kept the women’s cause in the media spotlight for months to come.

woman suffrage pickets at white house LOC (1917)

woman suffrage pickets at white house LOC (1917)by Harris & Ewing

National Women’s History Museum

Paul and her supporters built upon their success by staging protests in front of the White House. They created media-friendly opportunities to keep their message front and center for the American public.

Alice Paul (Sep 3, 1920)

Alice Paul (Sep 3, 1920)by Harris & Ewing

National Women’s History Museum

Paul wanted suffragists to organize more parades and protests to get the public’s attention. She hoped this strategy would help secure the passage of a federal suffrage amendment. NAWSA, however, opposed these militant tactics. Its leaders preferred state-by-state campaigns and traditional methods like petitioning legislatures and lobbying politicians. Soon after the parade, militant suffragists (under Paul’s leadership) broke away from NAWSA and founded the Congressional Union. In 1917, they renamed their group the National Woman’s Party (NWP).

College day in the picket line (1917)

National Women’s History Museum

College day in the picket line (1917)

National Women’s History Museum

While protests at the White House seem common today, the NWP organized the first picket in January 1917. Through the cold and rain, suffragists with banners stood at President Woodrow Wilson’s gates on and off throughout the year. Even as the United States entered World War I, the NWP continued to picket in front of the White House. Their choice angered politicians and some of the public, who believed the picketers were unpatriotic.

[In front of National Woman's Party headquarter... (1920)

[In front of National Woman's Party headquarter... (1920)by Library of Congress

National Women’s History Museum

Passing the 19th Amendment

The combination of NAWSA’s war efforts and the publicity attracted by the NWP's pickets of the White House led to widespread support for woman suffrage. Although President Woodrow Wilson previously had refused to endorse suffrage, in September 1918 he addressed the Senate in favor of votes for women. He appealed to patriotic arguments for suffrage when he asked representatives, “We have made partners of the women in this war; shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?”

Pen used to sign the Woman Suffrage Joint Resol...

Pen used to sign the Woman Suffrage Joint Resol...National Women’s History Museum

The 19th Amendment states: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” Congress passed the amendment in June 1919. The NAWSA and NWP suffragists lobbied local and state representatives to ensure its subsequent ratification by the states.

The Suffragist "At Last" (Jun 21, 1919)

The Suffragist "At Last" (Jun 21, 1919)by The Suffragist

National Women’s History Museum

Harry Burn, a young representative from Niota, Tennessee, cast the deciding vote to ratify the 19th Amendment. His "yes" vote, encouraged by a letter from his mother, broke a tie and caused Tennessee to become the 36th state to ratify the 19th Amendment making it become law.

Poster, "ERA Yes" NMAH (1988)

Poster, "ERA Yes" NMAH (1988)National Women’s History Museum

Equal Rights Amendment (ERA)

After the ratification of the 19th Amendment on August 18, 1920, female activists continued to use politics to reform society. NAWSA became the League of Women Voters. In 1923, the NWP proposed the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) to ban discrimination based on sex. The League of Women Voters and efforts to pass the ERA continue today.

ERA Charm Bracelet (1) NMAH (1972)

ERA Charm Bracelet (1) NMAH (1972)by Alice Paul

National Women’s History Museum

This is one of several charm bracelets started by Alice Paul in 1972, symbolizing the states that had voted to ratify the ERA.

March on Washington (Aug 28, 1963)

March on Washington (Aug 28, 1963)by US Government

National Women’s History Museum

Setting a Precedent

The 1913 Women’s Suffrage Parade set a precedent for future large-scale demonstrations in the Nation’s Capital.

March on Washington Singers (Aug 28, 1963)

March on Washington Singers (Aug 28, 1963)by National Archives and Records Administration

National Women’s History Museum

March on Washington

More than 250,000 people gathered in Washington, DC on August 28, 1963 for a political rally known as the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Organized by civil rights and religious organizations, it was designed to illuminate the political and social challenges confronting African Americans. The March, which became a key moment in the growing struggle for civil rights, culminated in Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, a spirited call for racial justice and equality.

women's march 2017 (Jan 21, 2017)

women's march 2017 (Jan 21, 2017)by Liz Lemon

National Women’s History Museum

Women's March

The January 21, 2017 Women’s March followed the legacy of the 1913 Suffrage Parade using pageantry and symbolism to garner media attention. Many women wore suffrage sashes honoring the suffragists that marched before them and pink hats as a sign of solidarity.

Suffrage Parade (Mar 3, 1913)

Suffrage Parade (Mar 3, 1913)by Library of Congress

National Women’s History Museum

Leaving a Legacy

The 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession through Washington, DC had a lasting impact on political and social demonstrations in the United States. These couragous women set a precedent encouraging future generations to stand up and fight for what they believe in.

Credits

NWHM Director of Program: Elizabeth L. Maurer

Supporting Text: Allison K. Lange, PhD

Edited and Updated: Cara Bennet, NWHM Intern