Why My Grandmother Wound Up in the Mob

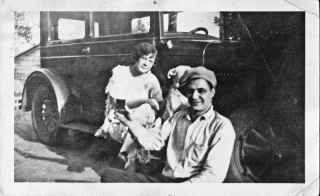

Minnie on a rum run.

In 1914, my grandmother, Minnie, became a single mother. She tried to convince the nurses at the Women's Homeopathic Hospital, in Philadelphia, that she was a married woman, but they weren't buying it. They checked the “illegitimate” box on my dad's birth certificate. Soon after, Minnie fell into crime with the Mob in Chicago.

Minnie on Drexel Boulevard in Chicago, about 1929

At age 19, Minnie was engaged to be married to Davis, a traveling salesman from Richmond, VA. She had dropped out of high school a few years before, to work, so she could contribute to her upkeep and that of her parents. She and Davis went to dances together in his automobile, a rare and glamorous item in 1914. According to her sister, Lily, writing in a letter to my dad, “She fell head over heels. Then anyone is vulnerable.”

When Minnie's father, a Danish immigrant, learned she was pregnant, she was kicked out of the family home. It didn't matter that her still handsome father had recently conducted an extramarital affair. His wife, Mommie, had given him a managerial job in the dress shop she owned as a ladies' tailor. She intercepted love letters written to Poppie, revealing a love affair between her husband and the forelady of her shop. That prompted Mommie to quit the shop and their home all together. Poppie remained, running the dress shop, or rather ruining the dress shop, “spending the money on women,” according to Lily. The shop's finances and reputation suffered. Mommie and Poppie got together again, but retired shortly thereafter, letting their many grown children support them.

Who knows what their brothers were up to, when it came to sex. Minnie's older sister Olga had been pregnant before she married the father of her baby. He was a drunk and a bad provider. However, Olga married him to legitimize her pregnancy and make it socially acceptable. In Minnie's case, sure, there was a guy.

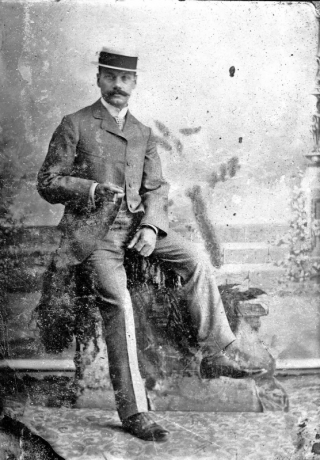

Poppie

But he had vamoosed by the time she had that baby. As Lily wrote, “When trouble came, his family made it hard to trace him.”

Why didn't he marry her?

After all, they were engaged. Davis's father, Harry, was the son of a wealthy, antebellum, slave-owning planter. Harry was also the president of a dry goods company. One of my Davis cousins, whom I met as a result of writing the book, Secret Life, Secret Death, told me, “the Davises were very particular about who their children married.” Okay, so marriage to a pregnant, high school drop out, the working daughter of disgraced, retired, immigrant tailors probably wasn't what the president of his own company had in mind for his son, Davis.

There was another reason Davis disappeared. Davis had a serious, double legal liability—for breach of promise, when he promised to marry Minnie, and for bastardy, which we now call paternity, either of which could result in expensive punitive damages. I found on his 1917 draft card, he was working as an adjuster for International Harvester way down in Jacksonville, Florida.

In 1914, the Wisconsin Vice Commission reports a legal case, in which a young woman met a man at dances twice a month, where he bought her drinks. But one evening, they left the dance hall ostensibly to get something to eat at a restaurant. But instead, he took her to a rented room, where he promised to marry her, then locked the door, pocketed the key and raped her. The next day the same scenario was repeated, except the man brought a friend of his, who also raped her. “After that I was brought in the family way,” her testimony reads. “He offered me $300 because he could not marry me, because his father would not have it.” She miscarried. The Wisconsin State Supreme Court awarded her $3,650 in damages for breach of promise. In 1913 that amount was several times the annual income of most young men.

What happens to the woman?

So, Minnie had been abandoned by her fiance and her family. Two of Minnie's brothers wanted to take her in, but their wives objected because they were afraid of damaging their own reputations. That's how socially unacceptable it was to have a single mom living in your household. Minnie wound up living with her older sister Olga. Uneducated women like Minnie were not paid a living wage in 1914. They had to be subsidized by living in their family home. But Minnie couldn't work at all, because no one would hire a single woman with a baby.

Minnie (seated) and Lily (standing) in Fairmount Park in Philadelphia, taken by one of their artist brothers

Lily wrote, “She grabbed at the first straw, which was all wrong. That was the greatest tragedy. By nature your mother was not born for that life... Only dreamed of love, home and family.” What was Lily referring to? Both Davis and Minnie's father knew that women who had babies out of marriage were doomed. A “girl in love is up against a cruel situation,” as Lily wrote.

Here is the testimony of a witness to the Teasdale Commission, in the Wisconsin Vice Report, [1914] in the statement of witness MXE:

The man will take the girl out and tell her how much he loves her, and pretty soon he has the best of her [i.e. her virginity] through promises of marriage. He says, ‘well, now if anything happens, I will marry you.’ Pretty soon the poor girl is gone [i.e. pregnant]. She is thrown out of her home. She is in bad at home. You are not going to employ her, because she has a bad name. Where is the woman going? The last resort for her is a sporting house [i.e. a brothel].

What happens to the man?

The man has no punishment at all. He can go to your [exclusive]_______Club, or to your churches and can marry the daughter of the richest man in the city... The ladies will pat him on the back and put him up for the highest office in the city.

Who was this witness MXE who understood so clearly the implications of a love affair? A cathouse madam.

Yeah, it was a “cruel situation” for a girl who had fallen in love. Minnie was now headed for a life of crime with the Mob. But all Davis had to do was to lay low, for a little while. Then he could come back home and it was life as usual for him. Turns out, the woman Davis did marry, two years after abandoning Minnie, was a college graduate, the daughter of wealthy plantation-owning parents. Davis lived out his life into his 60's, as an accountant for his sister's laundry company in Washington, DC. Perhaps the loss of Minnie and their baby haunted Davis for the rest of his life, because he never had any more children. As perspicacious Lily writes, “Maybe he suffered too. One never knows.”

Minnie, on the other hand, was consigned to a living hell. She was “easy pickins” for human traffickers, who lied to her to get her out of her home turf of Philadelphia and into the Chicago Mob. Through these lies, Minnie and my toddler dad landed in the worst neighborhood, in the hands of the most crooked people, in the city of Chicago, infamous for its corruption. And that is another story!

Genevieve Davis is the author of the book, Secret Life, Secret Death, the story of a young mother who fell into crime with the Mob. She is also the director of the feature documentary, Secret Life, Secret Death. You can learn more about her work as a director, writer and artist at www.october7thstudio.com. You can read the first chapter of the book and see clips from the film at http://october7thstudio.com/Secret2.htm. The book Secret Life, Secret Death is available at http://october7thstudio.com/Secret2.htm and on Amazon.com

- Addams, Jane. A New Conscience and an Ancient Evil, Macmillan Company, New York 1912

- Chicago Vice Commission. The Social Evil in Chicago, Chicago: Gunthorp-Warren Printing Company, 1911

- Reitman, Ben L. The Second Oldest Profession, Vanguard, 1931

- Parker, Joseph. “How Prostitution Works," http://www.prostitutionresearch.com/how_prostitution_works/000012.html.

- Vice Commission of Philadelphia. Published by the Commission, 1913.

- Wisconsin Legislature. Committee on White Slave Traffic and Kindred Subjects, Report and Recommendations of the Wisconsin Legislative Committee to Investigate the White Slave Traffic and Kindred Subjects, 1914.

- All photographs provided by Genevieve Davis.