The Trailblazing Women of Stand-Up Comedy

The story of the female pioneers of American stand-up comedy often begins and ends with icons Phyllis Diller and Joan Rivers. Perhaps there is some discussion of Roseanne Barr and her eponymous sitcom, Roseanne (1988–1997), or Ellen DeGeneres coming out on- and off-screen with her sitcom, Ellen (1994–1998), but few others garner serious attention. This cursory narrative leaves out the many entertaining ways that lesser-known female comics made their mark in stand-up comedy, from its earliest years to present day. From Sophie Tucker, who got her start in Vaudeville singing racy songs, to Elayne Boosler’s self-financed 1986 special, Elayne Boosler: Party of One, to Ali Wong’s gritty depiction of pregnancy and childbirth in 2016’s Baby Cobra, women have long made their voices a vital part of the American comic tradition.

Sophie Tucker, a Jewish singer, debuted in Vaudeville acts in 1906, performing in blackface because producers thought her too overweight and unattractive to sing as a white woman. Though successful in blackface, she despised the form and sought to vary her act. Soon, she found that audiences enjoyed the suggestive content of her racier songs. She attributed her ability to amuse rather than scandalize to her large figure, which flouted traditional notions of female beauty and restraint. During her decades-long career, Tucker performed cheeky songs such as “Make Him Say Please,” “No One Man is Ever Going to Worry Me,” and “You’ve Got to Make it Legal, Mr. Siegel.” Part of the appeal of Tucker’s songs came from their blended roots. She drew on both traditional Jewish music as well as African American blues and bawdy songs. Tucker frequented Black clubs in New York and Chicago, where she was influenced by the double (and single) entendres in the lyrics of Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey.

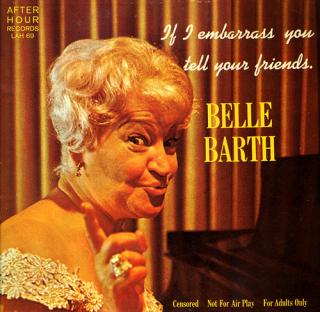

Another Jewish female comic and singer, Belle Barth, was one of several bawdy female comics of the mid-20th century who were inspired by Tucker. (Others included Pearl Williams and Totie Fields.) In 1960, Barth told her audience, “I know clean stories. I don’t make money with them, but I know them.” Famed comic Lenny Bruce, who was known for his battles with the authorities over the “obscene” nature of his stand-up, opened for Barth early in his career. Bruce is said to have confessed that “it was really Barth who was the sickest of them all.” In fact, Barth faced similar battles as Bruce: She was arrested and fined on lewdness charges in 1953, was sued numerous times, and was eventually banned from radio and television.

Despite such obstacles, Barth and her contemporaries still achieved commercial success. Party albums, the term for records that featured explicit material, became blockbusters by the early 1960s. Producer Stanley Borden told Billboard in 1961 that female comics’ party albums outsold those of male comics. Barth released 11 albums and reportedly sold two million records. In addition to the party albums, the bawds performed in front of sold-out crowds in prominent clubs and commanded high salaries. Barth and another comic, Patsy Abbott, even owned their own nightclubs in Miami in the 1950s and 1960s.

Jackie “Moms” Mabley, the most well-known African American female comic of the era, toured segregated theater circuits and performed for all-Black audiences across the country from the 1920s through the 1950s. During this time, Mabley played the Apollo stage more than any other performer and earned up to $10,000 per week. By the early 1960s, party albums helped her popularity cross over to white audiences. The last years of her career were marked by television appearances, performances at The Kennedy Center and The Playboy Club, and invitations to visit the White House under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson.

Like the Jewish bawds, Mabley played up her sexual folk humor—her colloquial dialect and gossipy, conversational tone endeared her to fans—and by asserting her political opinions, ones indelibly shaped by her experiences as a Black woman in Jim Crow America. For example, in Moms Mabley at The Playboy Club (1961), Mabley offered her take on traveling to the South: “I’m not goin’ to let the Greyhound take me down there and the bloodhounds run me back.”

Robin Tyler and Pat Harrison were a comedic duo that initially billed themselves as sisters (rather than the lovers they were) when they started performing in the late 1960s. Soon, however, they acknowledged their homosexuality and made feminism a central component of their repertoire, a move Tyler credits for their success. Feminist humor, Tyler claimed, gave women the opportunity to make the society oppressing them the target of their jokes, rather than themselves. Tyler and Harrison released the first explicitly feminist comedy album in 1972, Try It—You’ll Like It, which they followed in 1973 with Wonder Women. They included jokes intended to titillate (“I don’t want to say I got attached to my vibrator,but last Valentine’s Day I sent it two dozen roses”), as well as politically motivated material (a woman asks her boss why she’s paid less than her male coworker: “Because you can’t stand up to pee, Mary. That’s worth at least 40%.”)

Tyler began performing on her own in the mid-1970s, and in 1979 released the album Always a Bridesmaid, Never a Groom, the first openly gay or lesbian comedy album. That same year, Tyler became the first stand-up comedian to perform such material on national television, on Showtime’s 1st Annual Funny Women’s Show hosted by Phyllis Diller.

Tyler found her home on the feminist comedy circuit that grew out of the women’s liberation movement. Though it was certainly niche, this circuit flourished from the mid-1970s into the early 1990s. It consisted of women’s music festivals, coffeehouses, bookstores, and other performance spaces devoted to feminist (and largely lesbian) expression. Such spaces attracted audiences that felt alienated by the misogynistic environments of mainstream music and comedy venues. Lesbian comics such as Kate Clinton, Lea DeLaria, Karen Williams, and Marga Gomez gained fan followings as they played these spaces that catered to feminist audiences—long before Ellen DeGeneres publicly came out in 1997.

At the same time, mainstream stand-up comedy was experiencing a boom in popularity from the late 1970s through the early 1990s, with comedy clubs popping up across the country. The field was still very much male-dominated—female comics faced hecklers and hostile audiences, and bookers, as has long been the case, were reluctant to include more than one woman per show—but a growing number of women comics took to the stage.

Elayne Boosler began doing stand-up in the early 1970s after working as a waitress at The Improv, a comedy club in New York City. Her act consisted of jokes about her experiences as a single (heterosexual) woman and as a comedian, and the impossible expectations of both. One such joke was her take on the sexual double standard: “Men want you to scream, ‘You’re the best,’ while swearing you’ve never done this with anyone before.”

Despite frequently being hailed as the next big success, Boosler could not achieve the same feats as her male peers. She booked her first spot on The Tonight Show only when Helen Reddy guest-hosted in 1977. Later that year, she performed on the show when Johnny Carson was hosting, but she was assigned hacky, self-deprecating material she refused to use. Afterward, Carson reportedly told his comedy booker, “I don’t ever want to see that waitress on my show again.”

Boosler continued to make a living on the road, playing clubs across the country. Fellow comic Richard Lewis told The New York Times in 1984 that Boosler was “the Jackie Robinson of my generation” for breaking into the ranks of male stand-ups. But, after touring for 12 years, she still couldn’t get a cable special of her own. While the men she came up with were on their second specials, female comics were yet to film even one. So Boosler decided to produce one herself, financing it with her life savings. In 1985 she filmed Elayne Boosler: Party of One, but it sat untouched for over a year. Eventually, new management took over at Showtime and the special aired in 1986, but, according to Boosler, it was only after one executive’s wife pressured him to buy it. The special was an immediate success and Boosler went on to produce three more specials for Showtime over the next five years.

Today, more women comics are at the top of the field than ever before and they continue to make original and pioneering contributions to the genre. Ali Wong’s 2016 special, Baby Cobra, made headlines as the first comedy special filmed by a pregnant comic. Clad in a formfitting dress while eight months pregnant, Wong detailed the challenges and indignities of fertility treatments, miscarriages, pregnancy, and childbirth—topics not often featured in a comedy special, let alone from a firsthand perspective. The special made such an impact that the Smithsonian National Museum of American History requested that Wong donate the iconic dress she wore onstage. After Baby Cobra’s success, Wong released a second special, Hard Knock Wife, in 2018, which she filmed while pregnant with her second child.

Tig Notaro is known for her openly raw performance in 2012’s Live, in which she recounted her recent breast cancer diagnosis, one of several traumatic experiences for her at the time. In her 2015 special, Boyish Girl Interrupted, she performed the final 20 minutes shirtless, putting her mastectomy scars on full display. Notaro continues to innovate within stand-up comedy. HBO recently announced it will release Notaro’s latest project, the first-ever fully animated stand-up special, this summer.

The comic hopefuls of tomorrow, regardless of gender, can find a wealth of inspiration in the creative, resourceful, and courageous tradition of talented women who have helped shape stand-up comedy throughout its history.

Mariana Brandman is NWHM’s 2020–2022 predoctoral fellow in women’s history.

Sarah Blacher Cohen, “The Unkosher Comediennes: From Sophie Tucker to Joan Rivers,” in Cohen, Jewish Wry: Essays on Jewish Humor (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987), 110.

June Sochen, “From Sophie Tucker to Barbra Streisand: Jewish Women Entertainers as Reformers,” in Joyce Antler, et al. Talking Back: Images of Jewish Women in American Popular Culture, (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England [for] Brandeis University Press, 1998), 72, 74.

Belle Barth, If I Embarrass You, Tell Your Friends, After Hour B0072CPHTS, 1960.

Josh Kun, “‘If I Embarrass You, Tell Your Friends’: The Musical Comedy of Belle Barth and Pearl Williams,” in Bruce Zuckerman, Josh Kun, and Lisa Ansell, The Song Is Not the Same: Jews and American Popular Music, vol. 8, (West Lafayette, Ind.: Purdue University Press, 2011), 92.

Bob Rolontz, “After Hours, Surprise Lend Spice, Sales to Nation’s Record Markets,” Billboard Music Week, October 23, 1961.

Giovanna P. Del Negro, “From the Nightclub to the Living Room: Gender, Ethnicity, and Upward Mobility in the 1950s Party Records of Three Jewish Women,” in Simon J. Bronner, Jews at Home: The Domestication of Identity, vol. v. 2, (Oxford: The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2010), 189–190.

Del Negro, “From the Nightclub to the Living Room,” 190.

Darryl Littleton, Black Comedians on Black Comedy: How African-Americans Taught Us to Laugh. (New York: Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, 2006), 79.

Mel Watkins, On the Real Side: A History of African American Comedy from Slavery to Chris Rock. (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 1999), 514 and Elsie A. Williams, The Humor of Jackie Moms Mabley: An African American Comedic Tradition. (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1995), 50.

Watkins, On the Real Side, 391–392. Williams, The Humor of Jackie Moms Mabley, 48.

Moms Mabley, Moms Mabley at the Playboy Club, Chess, 1961.

Rebecca Krefting, All Joking Aside: American Humor and Its Discontents, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014), 141–145.

Robin Tyler & Pat Harrison, Try It—You’ll Like It, Dore Records LP 327, 1972. Tyler & Harrison, Wonder Women, 20th Century Records T-413, 1973.

Krefting, All Joking Aside, 141.

Yael Kohen, We Killed: The Rise of Women in American Comedy, 1st ed. (New York: Sarah Crichton Books, 2012), 121. Kohen, We Killed, 146–147.

Phil Berger, “The New Comediennes,”

The New York Times, July 29, 1984, sec. Magazine. http://www.nytimes. com/1984/07/29/magazine/the-new- comediennes.html.

Ali Wong, “Ali Wong Shares the Story Behind That Stand-up Special Dress,” In Style, Nov. 15, 2019. https://www.instyle.com/ celebrity/ali-wong-pregnancy-dress-essay “Tig Notaro Returns To HBO With Animated Stand Up Special,” Warner Media, April 30, 2021. https://pressroom.warnermedia. com/us/media-release/hbo-0/tig-notaro- returns-hbo-animated-stand-special

Elayne Boosler: Party of One, directed by Steve Gerbson, Showtime, 1986.

Photo Credits (from top to bottom):

Sophie Tucker. Photo credit: Bain News Service photograph collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Jackie “Moms” Mabley in her stage persona from a guest appearance on the Smothers Brothers television program. Photo credit CBS Television, public domain.

Belle Barth, “If I Embarrass You, Tell Your Friends” album cover. Photo credit: “Belle Barth, ‘If I Embarass You, Tell Your Friends’” by Max Sparber, licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Comedian Elayne Boosler performs on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson on September 15, 1977. (Photo by: Fred Sabine/NBCU Photo Bank/ NBCUniversal via Getty Images).

Comedian Ali Wong. Photo credit “Ali Wong, August 22” by Jason Baldwin, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.