Mythbusting the Founding Mothers

We all can picture the Founding Fathers, gathered in Independence Hall in Philadelphia, debating what to do about tyrannical Britain, and finally signing their names onto the Declaration of Independence. But what about the Founding Mothers? Often the women of revolutionary America are entirely forgotten. But women were alive during the Revolutionary War and did things worthy of remembrance just like male counterparts. During this time women were often relegated to the home and expected to behave and not make waves. But did they? Let’s examine some myths about women during the Revolutionary War and try to find the truth.

1. Women did not own businesses or have employment outside of the home.

This one is unequivocally false. Thousands of women in colonial America had paying jobs outside of the home. Some even ran their own businesses. Just two such women were Betsy Ross and Mary Katherine Goddard.

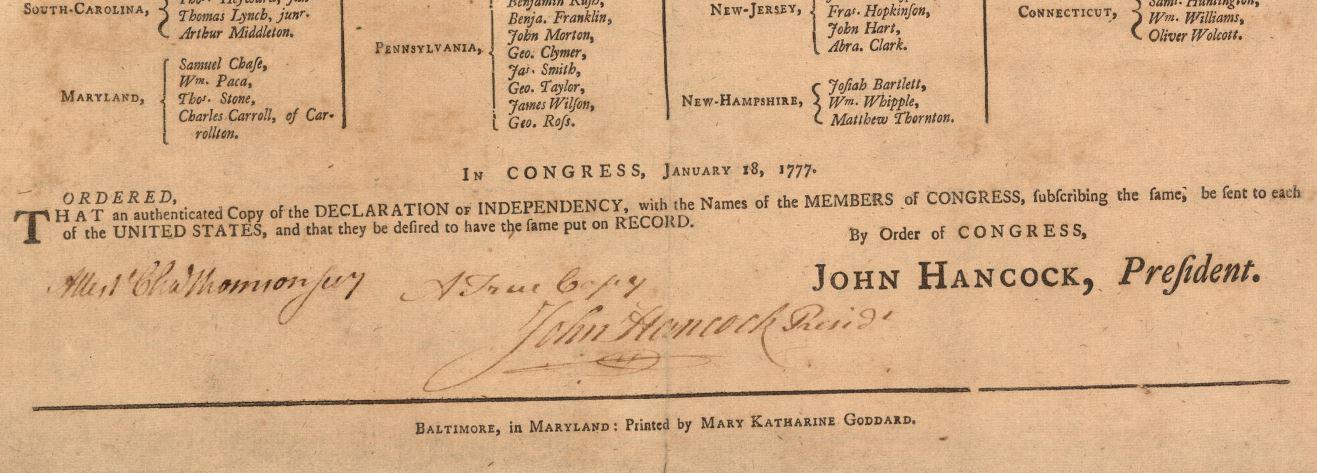

Mary Katherine Goddard's name at the bottom of the Declaration of Independence.

Mary Katherine Goddard (alternately spelled Katharine) is someone you’ve probably never heard of. She owned a publishing house in Baltimore, Maryland. In addition to her printing business, she ran the Baltimore post office, a bookstore, and published a newspaper, the Maryland Journal. Goddard was the first printer to publish the Declaration of Independence in its entirety. Previously only the text of the declaration and John Hancock’s name had been printed. With Goddard’s printing, all the signers names were included and she included her name at the bottom as well, making her a defacto signer of the Declaration. By including her name, she was putting herself at risk for treason charges as well. Goddard bravely used her company in aid to the Revolution at a time when women in business and politics was rare.

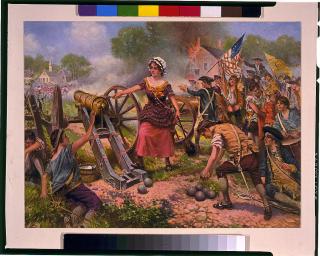

"Then, now, and forever!" c. 1908.

Betsy Ross, along with her husband John Ross, were upholsterers in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She actively worked and made money as an upholsterer and may have sewn and sold flags during the last few years of the Revolutionary War. One of the Ross’ best-known customers was General George Washington. According to period sources, on September 23, 1774, Washington made a payment for three bedcoverings to “Mr. Ross the upholsterer” in Philadelphia. It is more than likely that Mrs. Ross assisted in the creation of these bedcoverings for Washington.

Side Myth: While Betsy Ross was an upholsterer and may have made flags, there is little to no evidence to support the claim that she made the first American flag at the behest of General Washington. The first mention of Ross making the flag comes from her grandson, William Canby, in 1870. He introduced his evidence to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in the hopes that his grandmother would be remembered for her accomplishments. His evidence was made up of affidavits from family members, none of whom were alive when the supposed flag making took place. Canby claimed that he heard his grandmother time and again tell the story of how Washington came to her to ask her to make the flag. Unfortunately, there is no definitive historical evidence that can be found tying Washington and Ross to the creation of the American flag. We may never know exactly how, when, and by whom, the first American flag was created but we do know that she had a job that brought in money.

2. Women were not involved in the war efforts and did not participate in the Revolutionary War.

False! In fact, women were a constant presence in military camps throughout the Revolutionary War. There were thousands of camp followers including women and children. They were there for different reasons. Some were following their husbands or another male family member, while others were looking for steady employment and got jobs as laundresses or cooks. Martha Washington, for instance, stayed at every winter encampment with her husband during the war. While in camp, she formed sewing circles to make socks and clothing for the soldiers and organized aid and supplies for the hundreds of ailing men. Not all women stayed in camp though. There were some who actually got involved in the fighting and served in the thick of battles. Deborah Sampson, Mary Ludwig Hays McCauley, and Margaret Cochran Corbin were just some of the women known to have fought on the front lines.

Deborah Sampson was a teacher and a weaver, but in 1782, after years of war, she decided to join the fight. She dressed as a man and joined the Fourth Massachusetts Regiment as Robert Shurtleff. She was an adept soldier, participating in hand-to-hand combat and even leading a group to capture 15 men holed up in a Tory home. At one point, Sampson was shot in the left thigh and to escape detection she dug the bullet out herself. She was finally discovered about a year and half into her service when she became ill and lost consciousness. Sampson was honorably discharged on October 23, 1783 and received a pension from the Massachusetts government for her military service.

Molly Pitcher c. 1911.

Mary Ludwig Hays McCauley and Margaret Cochran Corbin have very similar stories: both women were camp followers; both women were tasked with bringing water to the front lines during battle; and when their husbands collapsed, both women stepped up to man the cannons and continued fighting until the battle concluded. McCauley (Hays at the time) was at the Battle of Monmouth on June 28, 1778. Her husband collapsed from supposed heat exhaustion while manning his cannon, she stepped up, and took her husband’s place. Multiple soldiers at that battle corroborate McCauley’s story.

Corbin was at the Battle of Fort Washington on November 16, 1776 when her husband was killed. Her story is a bit different because she was wounded in the process, sustaining three gunshot wounds. Corbin survived the battle and successfully gained a pension along with a clothing allowance. After her death in 1800, she was buried along the shore of the Hudson River but was later reinterred at the United States Military Academy at West Point, the only female Revolutionary War veteran buried there. Both McCauley and Corbin are believed to be the inspiration for the legend of Molly Pitcher.

3. Women were demure, stayed at home, and did not get involved in political discourse or activities.

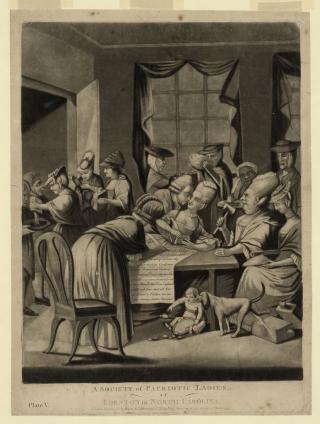

Political cartoon satirizing the women involved in the Edenton Tea Party. Published March 25, 1775 in London.

This could not be more wrong. While many or most women did shy away from political discourse and public acts, there are many examples that prove this was not universally the case. The best example comes from the Edenton Tea Party. We all know of the December 16, 1773 Boston Tea Party that was accomplished by an all-male band of Massachusetts colonists. The Edenton Tea Party occurred about a year later in Edenton, North Carolina. A group of 51 women, led by Penelope Barker, gathered for a meeting of the Edenton Ladies Patriotic Guild on October 25, 1774. They drank a concoction of local tea referred, to as “balsamic Hyperion,” and drafted a notice of protest against the British Tea Act of 1773. They wrote up a resolution stating their displeasure with the taxes and vowed to not buy British tea or cloth. News of the resolution made its way throughout the colonies and over to England where political cartoons satirizing the women were published. There is even some evidence that women took this a step further and burned their tea in Wilmington, North Carolina sometime in 1775.

On the other side of the fight was Molly Brandt, who was deeply involved in the Revolutionary War as a Loyalist. Brandt was a Mohawk Indian who spent a considerable amount of time gathering Native support for the British. She believed that native peoples would be best treated under British rule and she successfully brought five of the six Iroquois tribes to the British side. Because of her Loyalist leanings, her property in New York was taken by Patriots and she, along with thousands of other Mohawks, fled across the border to the Canadian frontier in November 1777. After the war Brandt and her brother Thayendanegea (also known as Joseph) successfully petitioned the British government for a pension. Today, Brandt is known as one of Canada’s Founding Mothers.

There are many myths surrounding Founding Mothers. By examining just a few myths, it is easy to see that women were involved in almost every aspect of the Revolutionary War. The women mentioned above, and countless others, all helped to shape this country into what it is today. They played a significant role in the political discourse of the era at a time when women were expected to stay home and take care of the family. While their stories may have been fictionalized over time, these women should be remembered for their lasting impact on America since the founding of this country.

- Canby, William “The History of the Flag of the United States.” Independence Hall Association, March 1870. Accessed July 11, 2017.

- Carney, Richard. “Edenton Tea Party.” North Carolina History Project. Accessed July 11, 2017.

- Cumming, Inez Parker. “The Edenton Ladies’ Tea-Party.” The Georgia Review 8 (1954): 389-395.

- Dvorak, Petula. “This woman’s name appears on the Declaration of Independence. So why don’t we know her story?” The Washington Post, July 3, 2017.

- Isaac, Amanda C. “Furnishings of the Chintz Room.” George Washington’s Mount Vernon, May 2016. Accessed July 11, 2017.

- Jasanof, Maya. Liberty’s Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011.

- Kickler, Troy L. “When Wilminton Threw a Tea Party: Women and Political Awareness in Revolution-Era North Carolina.” North Carolina History Project. Accessed July 11, 2017.

- Kickler, Troy L. “Wilmington Tea Party.” North Carolina History Project. Accessed July 11, 2017.

- Klaver, Carol. “An Introduction to the Legend of Molly Pitcher.” MINERVA: Quarterly Report on Women and the Military 12 (1994): 35.

- Leepson, Marc. “Five Myths about the American Flag.” The Washington Post, June 10, 2011. Accessed July 11, 2017.

- Miller, Marla R. Betsy Ross and the Making of America. New York: Henry Holt, 2010.

- Roberts, Cokie. Founding Mothers: The Women Who Raised Our Nation. New York: William Morrow, 2004.