Monopoly’s Lost Female Inventor

For generations, the story of Monopoly’s Depression-era origin story delighted fans.

Often tucked into the game’s box, the tale revolved around Charles Darrow, an unemployed man in Philadelphia who dreamed up the game in the 1930s. He sold the game to Parker Brothers, not only saving him and the company from financial ruin, but becoming wealthy—a Cinderella story made of cardboard and real-life Monopoly money.

The trouble is, it isn’t exactly true.

Monopoly’s roots begin not with Darrow, but with a woman—a progressive named Elizabeth Magie.

Magie is one of countless women whose contributions were minimized, largely ignored, or in some cases, deliberately erased. And with Monopoly, understanding the story of its true inventor provides a fascinating window into not only one woman’s life and times, but how the game that sits in many closets isn’t necessarily what we thought it was.

Born in rural Illinois in 1866, Magie lived a highly unusual life. Her father, James Magie, was an early force in the Republican Party, having traveled with Abraham Lincoln as he debated Stephen Douglas. He was an influential newspaper editor and political advocate, values he infused in his daughter—a feminist father far before his time.

The seeds of the Monopoly game were planted when Magie shared with his daughter a copy of Henry George’s best-selling book, Progress and Poverty, written in 1879.

As an anti-monopolist, James Magie drew inspiration from George, a charismatic politician and economist who believed that individuals should own 100 percent of what they made or created, but that everything found in nature, particularly land, should belong to everyone. George advocated for a “land value tax,” also known as the “single tax,” the general idea of taxing land, and only land, that could help shift the tax burden to wealthy landlords. Many Americans connected with his message in the late 1800s, when poverty and squalor were on full display in the country’s urban centers. The anti-monopoly movement also served as a staging area for women’s rights advocates and many abolitionists, like the Magies.

Women’s advocacy was a particularly impassioned cause of Elizabeth Magie and her willingness to push for equality would make national headlines. Finding it difficult to support herself on the $10 a week she was earning as a stenographer, Magie staged an audacious stunt mocking marriage as the only option for women. Purchasing an advertisement, she offered herself for sale as a “young woman American slave” to the highest bidder. Her ad said that she was “not beautiful, but very attractive,” and that she had “features full of character and strength, yet truly feminine.”

The goal of the stunt, Magie told reporters, was to make a statement about the dismal position of women. “We are not machines,” Magie said. “Girls have minds, desires, hopes and ambition.”

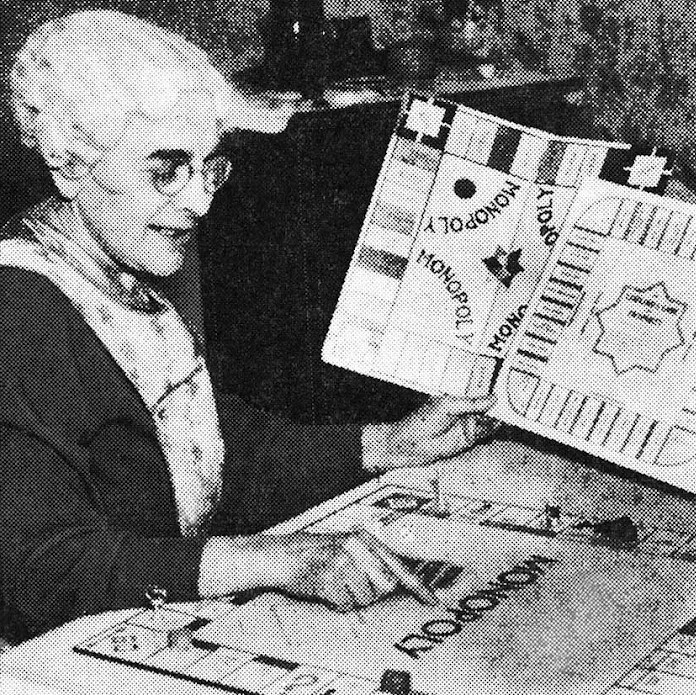

By the turn of the century, Magie had made her way to Washington, DC. Unlike most women of her era, she supported herself and didn’t marry until the advanced age of 44. In addition to working as a stenographer and a secretary, she wrote poetry and short stories and performed comedic routines onstage. She also spent her leisure time creating a board game that was an expression of her strongly held political beliefs.

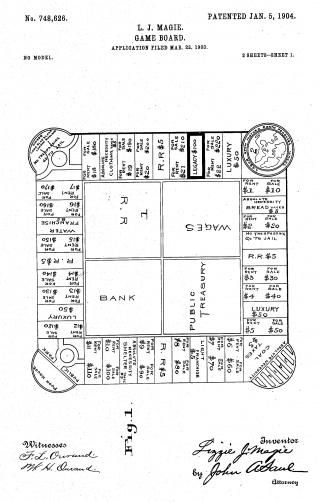

In 1904, Lizzie Magie patented her Landlord's Game, the forerunner to what millions of game players would later know as Monopoly. Among other things, her patent features the phrase Go to Jail, railroad spaces, and a Public Park space that predates Free Parking.

Magie filed a legal claim for her Landlord’s Game in 1903, more than three decades before Parker Brothers began manufacturing Monopoly. She actually designed the game as a protest against the big monopolists of her time—people like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller.

She created two sets of rules for her game: an anti-monopolist set in which all were rewarded when wealth was created, and a monopolist set in which the goal was to create monopolies and dominate opponents. Her dualistic approach was a teaching tool meant to demonstrate that the first set of rules was morally superior.

“It is a practical demonstration of the present system of land-grabbing with all its usual outcomes and consequences,” she wrote in a 1902 issue of the Single Tax Review. “It might well have been called the ‘Game of Life,’ as it contains all the elements of success and failure in the real world, and the object is the same as the human race in general seems[s] to have, i.e., the accumulation of wealth.”

In 1936, at the height of the Monopoly craze, Lizzie Magie spoke out in the pages of the Washington Evening Star against the Darrow creation story. The paper reported that she received $500 for her invention.

When she applied for a patent for her game in 1903, Magie was in her 30s. She represented the less than 1 percent of all patent applicants at the time who were women. (Magie also dabbled in engineering; in her 20s, she invented a gadget that allowed paper to pass through typewriter rollers with more ease.)

For Magie to put her ideas out in public so brazenly was something of a risk at the time. It would be seventeen more years before women gained the right to vote, and while innovations such as the typewriter and telephone had afforded new professional opportunities for women, common thought still held that they had little to contribute to the world of ideas. As one newspaper would put it in 1912, “they don’t use their brains as much as men.”

It wasn’t long before the monopolist rule set of her game would take hold. On some level, Lizzie understood that the game provided a context—it was just a game, after all—in which players could lash out at friends and family in a way that they often couldn’t in daily life. She understood the power of drama and the potency of assuming roles outside of one’s everyday identity. The popularity of the game spread, becoming a folk favorite among left-wing intellectuals, particularly in the Northeast. It was played at several college campuses, including what was then called the Wharton School of Finance and Economy, Harvard University, and Columbia University. Quakers, who had established a community in Atlantic City, embraced the game and added their neighborhood properties to the board.

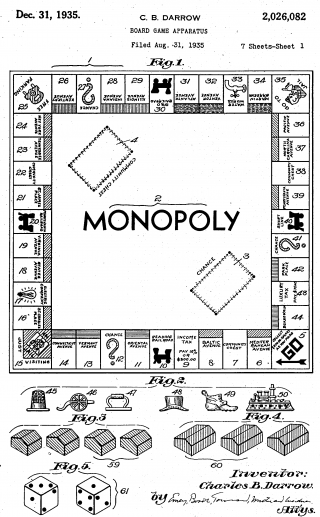

On December 31, 1935, Charles Darrow received his Monopoly patent, sparking controversy decades later as details surrounding Lizzie Magie’s Landlord’s Game and other early pre-Parker Brothers games surfaced.

It was a version of this game that Charles Darrow was taught by a friend, played, and eventually sold to Parker Brothers. The version of that game had the core of Magie’s game, but also modifications added by the Quakers to make the game easier to play. In addition to properties named after Atlantic City streets, fixed prices were added to the board. In its efforts to seize total control of Monopoly and other related games, the company struck a deal with Magie to purchase her Landlord’s Game patent and two more of her game designs not long after it made its deal with Darrow.

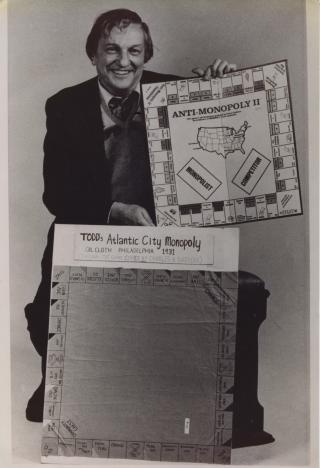

Ralph Anspach, inventor of Anti-Monopoly, became a board game detective, using early, pre-Parker Brothers boards as evidence of the game’s controversial origins in his case against Parker Brothers.

Magie’s identity as Monopoly’s inventor was uncovered by accident. In 1973, Ralph Anspach, an economics professor, began a decade-long legal battle against Parker Brothers over the creation of his Anti-Monopoly game. In researching his case, he uncovered Magie’s patents and Monopoly’s folk-game roots. He became consumed with telling the truth of what he calls “the Monopoly lie.”

Roughly 40 years have passed since the truth about Monopoly began to appear publicly, yet the Darrow myth persists as an inspirational parable of American innovation. It’s hard not to wonder how many other buried histories are still out there—stories belonging to other lost “Lizzie Magies” who quietly chip away at creating pieces of the world, their contributions so seamless that few of us ever stop to think about the person or people behind the idea.

But for Magie, even if it’s late, credit is finally being paid due. And our Monopoly games are better for it. Perhaps no one says it better than Magie herself in a 1940 edition of Land and Freedom, a Georgist publication: “What is the value of our philosophy if we do not do our utmost to apply it? To simply know a thing is not enough. To merely speak or write of it occasionally among ourselves is not enough. We must do something about it on a large scale if we are to make headway. These are critical times, and drastic action is needed.”

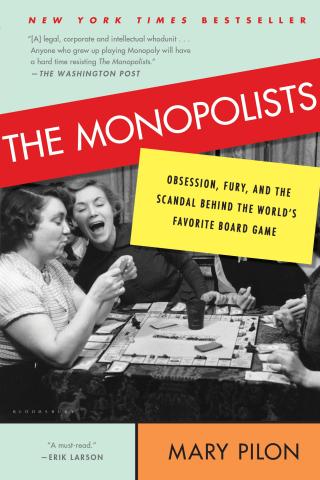

Mary Pilon is the author of The Monopolists and The Kevin Show.