Honoring Beverly Cleary

Beverly Cleary, 1971.

Beloved children’s book author Beverly Cleary turned 100 years old on April 12, 2016. Starting with Henry Huggins in 1950 and her last book Ramona’s World in 1999, Cleary wrote more than 40 children’s books that have sold 91 million copies and remain at the top of teacher and librarians’ recommended reading lists. Cleary died on March 25, 2021 at 104 years old.

Children in Cleary’s books are independent, enjoy being outside, and solve problems with the support of friends. They are realistic children who misbehave, get into trouble, and fight with their siblings. “I never reform anybody,” Cleary told The New York Post in 2006. “Because when I was growing up, I didn’t like to read about boys and girls who learned to be better boys and girls.” Today’s children are no different.

Beverly Cleary bucked the prevailing trends in children’s literature. What made her different?

Over the past 100 years, a trend in children’s literature has been to position adults as peripheral to children’s lives if not actively antagonistic. The Hardy Boys (1927) and Nancy Drew (1930) experience shockingly little adult supervision while repeatedly imperiling themselves. The Cat in the Hat (1957) wreaks havoc because the mother is away. Katniss Everdeen in The Hunger Games (2008) finds the adults in her life literally trying to engineer her death.

Various Beverly Cleary books

Cleary’s characters, on the other hand, while independent, often interact with adults as she examines the relationships between adults and kids. Cleary received Newbery Honors for Ramona and Her Father (1978), which traversed the family’s challenges when Ramon’s father unexpectedly loses his job. In Ramona and Her Mother—the 1981 National Book Award winner for Children's Fiction—a pre-adolescent Ramona worries about her parents’ unsettling quarrels and whether her mother has enough attention to go around. Cleary was awarded the Newbery Medal for outstanding children’s book in 1984 for her juvenile novel Dear Mr. Henshaw, in which a boy works through his parents’ divorce and adaptation to a new school through his correspondence with his favorite author. Though Cleary’s characters are independent, they are not left on their own. Caring adults populate their worlds.

In her youth, Cleary reminded the Washington Post, “mothers did not work outside the home; they worked on the inside. And because all the mothers were home—99 percent of them, anyway—all mothers kept their eyes on all the children.” Yet Cleary herself was a working mother who balanced her writing career with raising a young family with the help of a neighbor who watched her children while she wrote. In that, she was typical of many women in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s who increasingly returned to part time work to supplement family income. Cleary explored the dynamics of families with wage-earning mothers in several books starting in the 1970s. Her writing mirrored her and her readers’ real lives, making her novels relatable.

Over a half century of writing, Cleary’s work reflected changes in American society. Her characters faced challenges that remain highly relevant today such as a parent losing a job, loss of a favorite pet, divorce, and school yard bullying. Her stories reflect the issues women faced in the decades in which they were published, creating a literary, historic timeline of the 20th century.

When asked why her work has remained popular, she told The Atlantic, “I think it is because I have stayed true to my own memories of childhood, which are not different in many ways from those of children today. Although their circumstances have changed, I don't think children's inner feelings have changed.”

Beverly Cleary Books

Henry Huggins (1950)

Ellen Tebbits (1951)

Henry and Beezus (1952)

Otis Spofford (1953)

Henry and Ribsy (1954)

Beezus and Ramona (1955)

Fifteen (1956)

Henry and the Paper Route (1957)

The Luckiest Girl (1958)

Jean and Johnny (1959)

The Hullabaloo ABC (1960)

Beaver and Wally (1961)

Emily's Runaway Imagination (1961)

Here's Beaver! (1961)

Henry and the Clubhouse (1962)

The Real Hole (1962)

Ribsy and the PTA (1963)

Sister of the Bride (1963)

Two Dog Biscuits (1963)

Ribsy (1964)

The Mouse and the Motorcycle (1965)

Mitch and Amy (1967)

Ramona the Pest (1968)

Runaway Ralph (1970)

Socks (1973)

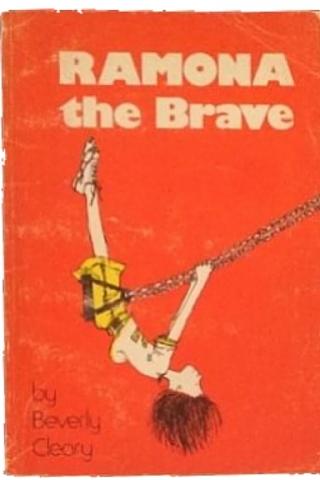

Ramona the Brave (1975)

Ramona and Her Father (1977)

Leave It to Beaver (1978)

Ramona and Her Mother (1979)

Ramona Quimby, Age 8 (1981)

Ralph S. Mouse (1982)

Young Love (1982)

Dear Mr. Henshaw (1983)

Lucky Chuck (1984)

Ramona Forever (1984)

The Growing-Up Feet (1987)

Janet's Thingamajigs (1987)

A Girl from Yamhill: A Memoir (1988)

Here Come the Twins (1989)

Mouse House Trio (1989)

The Twins Again (1989)

Muggie Maggie (1990)

Strider (1991)

Petey's Bedtime Story (1993)

My Own Two Feet: A Memoir (1995)

Ramona's World (1999)

Two Times the Fun (2005)