The History of Women in the Democratic Party

The Democratic party dominated US politics in the first half of the 19th century, winning all but two of the presidential elections between 1828 and 1856. At mid-century, the issue of slavery and its expansion into new territories fractured the party. It opened the door to the newly established Republican party and Abraham Lincoln’s 1860 election win. It would be seventy years before the Democrats regained dominance. They did so with the help of women.

Party Dominates Politics Until Civil War

The Republican party emerged as the Civil War’s political victor. While Democrats and Republicans traded Congressional majorities for the remainder of the 19th century, the White House proved elusive to Democrats. Democrats formed women’s groups during election years but dissolved them between election cycles, in contrast to Republican women who established on-going, active clubs starting in the 1880s. The socially conservative Democratic party expressed wary discomfort with women’s on-going engagement in public, political activities.

After the 19th Amendment passed in 1920, both parties developed strategies to mobilize women voters. The Democratic National Committee (DNC) recruited Emily Newell Blair in 1922 to organize a Women’s Division. Blair re-activated the moribund network of Democratic women’s clubs across the country, reconstituting them as political education forums. She organized speaker’s bureaus, produced a newsletter, and mailed a million educational leaflets. Blair reported organizing 1,000 local women’s Democratic clubs before the 1924 presidential election, bringing thousands of women into the party.

D.A. McDougal and Emily Newell Blair, 1924.

In spite of Blair’s efforts, presidential candidate John W. Davis was overwhelmingly defeated by Republican Calvin Coolidge in 1924. The DNC suspended its national operations following the devastating returns. Blair transferred her operations to the private Woman’s National Democratic Club (WNDC), along with the DNC’s physical records, which the party could no longer store after giving up its headquarters. For the next four years, the DNC relied on the WNDC for organizational support.

Resurrecting the Party

The Democrat’s 1928 presidential candidate, Al Smith, also lost to his Republican rival—Herbert Hoover. However, Smith’s savvy appointment of John J. Raskob as the new DNC chair proved key to reversing the party’s fortunes. Raskob, a brilliant fundraiser, not only retired over a million dollars in campaign debt, he also reconstituted the DNC’s professional organization. He revived the Women’s Division, hiring Nellie Tayloe Ross—the country’s first female state governor—as director. Sue White replaced Ross in 1930. Working in tandem with the WNDC, White developed a national outreach program. Before the June 1932 national convention, the network contacted women in 2,600 of 3,000 US counties including all the counties in 22 states. Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt defeated Hoover in 1932, securing the presidency with 57% of the popular vote and sweeping in Senate and House majorities.

Roosevelt recognized the Women’s Division’s pivotal role in his success and made it a permanent department in the DNC. He appointed Mary “Molly” Dewson as its new head. Dewson was a New York political ally as well as a close associate of Eleanor Roosevelt. Mrs. Roosevelt had recruited Dewson to work on FDR’s 1930 gubernatorial and 1932 presidential campaigns and knew her to be a supreme organizer.

I am a practical politician out to build up the Democratic party where it sorely needs it. - Molly Dewson, 1933

Molly Dewson, December 22, 1938.

Bringing in the Women

Dewson reached outside the party structure to build support among traditionally unaffiliated voters, including women. Saying “elections are won between campaigns,” Dewson developed a voter education program aimed at women. She urged local women’s clubs to appoint members as Reporters to keep abreast of New Deal programs and explain their impact at club meetings. In this way, she by-passed news organizations, many of which were critical of the New Deal, and ensured that people at the grassroots level would be informed of the benefits and impacts of government programs. By 1940, the program involved more than 30,000 women.

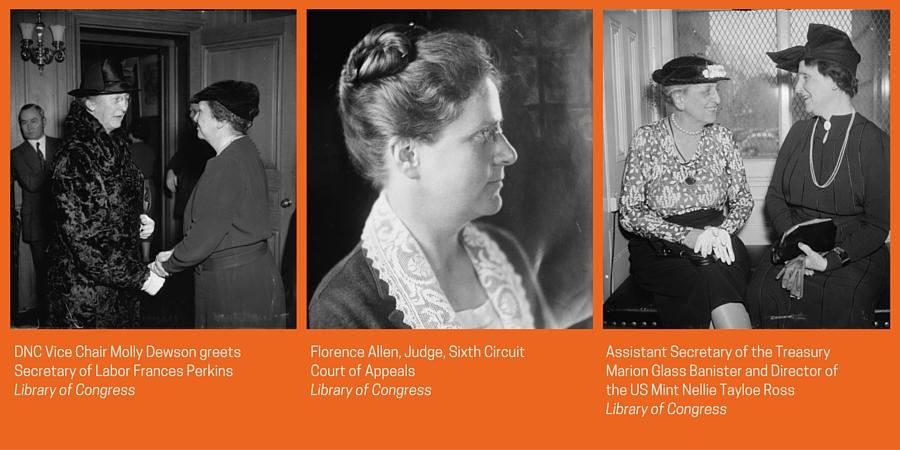

Dewson also focused on recognizing and rewarding loyal women party members. She capitalized on her relationships with both Roosevelts to establish a pipeline of women to appointed government positions. Dewson lobbied Roosevelt to appoint Frances Perkins as the first female cabinet secretary, heading up the Department of Labor. Dewson also secured appointments for the first female judge on the US Court of Appeals (Florence Allen, Sixth Circuit); first female Assistant Secretary of the Treasury (Marion Glass Banister); and the first woman Director of the US Mint (Nellie Tayloe Ross). Dewson herself was appointed to the Social Security Administration in 1937. Dewson did not neglect the party’s grassroots. She successfully secured new party rules requiring equal representation of men and women in leadership roles throughout the DNC.

A New Party for a New Era

Dewson’s efforts to bring women into the Democratic Party and reward their contributions paid off. During the 1936 election, more than 80,000 women canvassed door to door for Democratic candidates and distributed 83 million fliers. Sixty percent of the electorate voted for Roosevelt, the largest margin of victory since 1820. The army of women Dewson and her predecessors brought into the party helped to maintain Democratic control through five presidential elections.

The Democratic party transformed itself in the 1920s and 1930s. Women were key. The 19th-century party staunchly adhered to limited government. During the Depression, the party—with the assistance of Democratic women—redefined the relationship of government to the people, encouraging a more activist position. They transformed government into an instrument of change. While the extent of government’s role in enacting social and welfare policies continues to be debated, the belief that government has a role is settled.

Encyclopædia Britannica Online, s. v. “Democratic Party”, accessed July 18, 2016.

Freeman, Jo. A room at a time: how women entered party politics. Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002.

Gerring, John. A Chapter in the History of American Party Ideology: The Nineteenth-Century Democratic Party (1828-1892). Polity, Vol. 26, No. 4 (Summer, 1994), pp. 729-168.

Krook, Mona Lena, and Sarah Childs. Women, gender, and politics: a reader. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Leuchtenburg, William E. The FDR years: on Roosevelt and his legacy. New York: Columbia University Press, 1995.

O’Dea, Suzanne. From suffrage to the Senate: an encyclopedia of American women in politics. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 1999.

Ware, Susan. Beyond suffrage, women in the New Deal. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1981.