The History of Romance

The giving and receiving of valentines or love tokens dates to medieval times, but the origins of the modern celebration lie in the 18th century with the rise of romantic marriage. During the 18th century, society encouraged young people to select their marriage partners based on their romantic attachments. This was a decided change from past practice when marriages had been arranged to cement relationships between families or clans and to consolidate fortunes. Brides’ and grooms’ feelings were not of paramount consideration. While love and respect might be a byproduct of marriage, young couples had not entered into marriage with that expectation. That changed in the eighteenth century.

You know what to expect from me, as you have seen my character of a good wife. Suppose I tell you now, what I, in my turn, expect, and how you may best please me and make me happy.—Thus then I begin—Let me ever have the sweet consiousness of knowing myself the best beloved of your heart—I do not always require a lover’s attention—that wou’d be impossible, but let it never appear by your conduct that I am indifferent to you. - Margaret Davenport Coulter to John Coulter, May 10, 1795

As expectations increased that marriage would be built on a foundation of love rather than mutual, economic interest, the way that partners were selected had to evolve. When parents stopped making the selection, prospective lovers needed to find one another and then determine the extent of mutual attraction. Courtship became a distinctive phase of partner selection, and familiar rituals evolved. Young women, perhaps more than young men, often enjoyed the process of courtship as it represented a time of freedom and choice. The selection of a husband was the most important decision a girl would make, but it was also the most autonomous. Courting empowered young women. They decided who to accept or reject, and some wielded their power ruthlessly.

You know I have never with all my faults betrayed one symptom of vanity, but now if you should discover a little spice of it can you Wonder—just at this moment are at my entire disposal two of the Very Smartest Beaux this country can boast of… . There is much speculation going on as to the preference I shall give & tho I do not intend to practice one Coquettish air … yet for my own amusement do I intend to leave these speculating geniuss to their own conjectures … till I have made up my mind. - Eliza Ambler to Mildred Smith, February 1785

Courtship requires that prospective lovers reveal their feelings and that they do so more creatively and sincerely than their competitors. Exchanging Valentines became a popular way to express those feelings. A popular eighteenth-century Valentine form was a homemade love-letter puzzle. The writer intricately folded the paper, writing a different sentiment in each section. As the beloved unfolded the Valentine, her lover’s feelings were revealed. Many were sentimentally preserved and reside in museum collections today.

Reproduction Love Letter Valentine

Nineteenth Century Romance Evolves

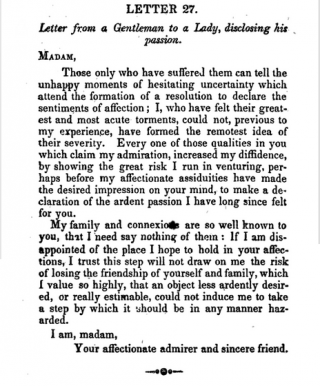

Romance blossomed in nineteenth-century American culture. Both men and women were encouraged to express their most intimate thoughts in letters. High literacy rates and a reliable postal service facilitated romantic communication. Letter-writing culture flourished. Letter-writing manuals provided sample love letter language for those who were not naturally adept at self-expression. Or, lovers could quote their favorite poets, drawing from an abundance of romantic literature.

Elizabeth Barrett published the love poems she composed to her future husband Robert Browning, at his insistence, after overcoming her reluctance to share their intimate correspondence.

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways. I love thee to the depth and breadth and height. My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight for the ends of being and ideal grace. I love thee to the level of everyday’s most quiet need, by sun and candle-light. I love thee freely, as men strive for right; I love thee purely, as they turn from praise. - “How Do I Love Thee? Let Me Count the Ways,” Sonnets from the Portuguese, Elizabeth Barrett Browning

The Fashionable American Letter Writer or the Art of Polite Correspondence. Containing a Variety of Plain and Elegant Letters on Business, Love, Courtship, Marriage, Relationships, Friendship, &c. 1839.

More casual lovers, those of less intimate acquaintance, were able to purchase ready-made Valentines in the mid-nineteenth century. The first commercial Valentines sold in the United States were produced by Mount Holyoke graduate Esther Howland. Following her college graduation in 1847, Howland began to produce and sell fancy, paper Valentines. In 1850 she expanded her operation, hiring local women to craft elaborate creations with ribbon, glitter, and paper lace in an assembly line fashion. Howland ran her New England Valentine Company until 1881 when she sold it to the George C. Whitney Company, headed by one of her former employees. The New England Valentine Company had annual gross sales of $100,000 at the end, demonstrating that romance could turn a profit.

Post Card Valentine, 1907.

Securing a Mate

Throughout the nineteenth century, middle and upper class married women were idealized for their role as mothers and helpmates. Whereas earlier generations recognized women as making economic contributions to households and family businesses, nineteenth-century social conventions diminished their role. Instead, their part--often called the Cult of Domesticity--was to create a pleasant and restorative environment for their husbands while raising children to be contributing citizens. When households began to be constituted as a breadwinner husband and homemaker wife, the practical advantages of marriage, such as the wife’s ability to economically manage a household, were minimized. While romantic love flourished, there was an increasing idealization of women as mothers and wives.

Women’s eligibility for marriage became increasingly tied to their appearance and social ability, though wealth and familial connections remained important factors to prospective partners. Men took the lead in partner selection, choosing which women to pursue while women waited to be selected. There was an expectation that everyone would eventually marry, both men and women, but men were expected also to establish a career and a public persona. For women, becoming a wife and mother was an achievement to aspire to. Therefore, women were discouraged from participating in activities that might make them less suited to marriage, such as higher education. Society was furthermore suspicious of women who did not marry, often characterizing them as deviants or old maids, and limiting their options.

Modern Romance

While romance remains a prime consideration in partner selection for twenty-first century women, the interest in selecting a partner has waned. In 2006, the Pew Trust found that only 16% of uncoupled Americans were actively looking for a partner. And when they are searching for love, marriage is not necessarily the romantic goal. In 2012, 23% of American men and 17% of women--over age 25—had never married, doubling from 1890 when 11% of men and 8% of women had never married. While marriage rates are down, cohabitation for unmarried men and women has increased. About a quarter (24%) of never-married young adults ages 25 to 34 lived with a partner in 2015. Social scientists have explored factors contributing to a decline in the marriage rate. They point to shifting public attitudes towards cohabitation, increasing acceptance of singledom, difficult economic times, and women’s increased economic independence. Romantic love in modern times has a different feel when women no longer see marriage as an end goal but rather a partnership between equals.

Coontz, Stephanie. Marriage, a history: from obedience to intimacy or how love conquered marriage. New York, NY: Penguin, 2006.

Elliott, Diana B., Kristy Krivickas, Matthew W. Brault, and Rose M. Kreider. "Historical Marriage Trends from 1890 - 2010: A Focus on Race Differences." May 2012.

Lystra, Karen. Searching the heart: women, men, and romantic love in nineteenth-century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.