Getting into the Games: Olympic Women

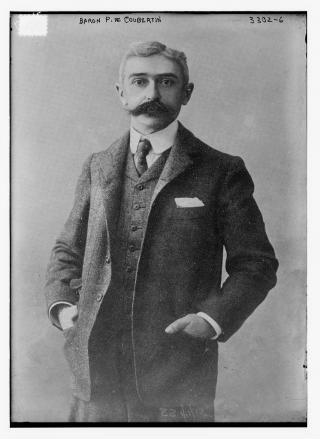

Baron Pierre de Coubertin, January 7, 1915.

Team USA's 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympic roster includes 131 women among its 284 members, the most women the US has ever sent to the winter games. This is a tremendous evolution from the very first Olympics in 1896, which excluded women. The Olympics’ founding organizer, Pierre, baron de Coubertin, envisioned a festival celebrating men’s sporting achievements. Popular culture promoted sports competitions as an outlet for men’s aggression that also encouraged moral fortitude. Because women were not supposed to be neither aggressive nor competitive, Coubertin and his fellow organizers intended that women’s Olympic participation be limited to that of spectator.

Women have but one task, that of the role of crowning the winner with garlands... In public competitions, women’s participation must be absolutely prohibited. It is indecent that spectators would be exposed to the risk of seeing the body of a woman being smashed before their eyes. - Pierre de Coubertin

Women Enter Olympic Competition

While women missed the first games in 1896, they appeared at the second and third. The 1900 Olympic games were held currently with the Paris World’s Fair. While women were not specifically included, they were not explicitly excluded. Seven American women competed in tennis and golf. Margaret Abbott won the women’s golf contest, becoming the first American woman to win first place in an Olympic event.

The third Olympics were held in St. Louis in 1904, also during a World’s Fair. The United States provided the vast majority of athletes. Six American women—the only female athletes attend—competed in archery, the only event open to women. Medals were first awarded in 1904, and Lida Scott Howell won three gold.

Making it Official

The London games in 1908 were the first to officially sanction women’s participation. National sports governing bodies and federations sanction athletic competitions and select Olympic national teams. While the American Olympic Committee refused to send women athletes in 1908, European women competed in tennis, archery, and figure skating.

The International Swimming Federation (ISF) first sanctioned women’s competitive swimming events in 1910, opening the door to women’s participation at the 1912 Stockholm games. America’s female swimmers did not compete in Stockholm because their sports governing body, the American Athletic Union (AAU), did not sanction women’s competitive swimming until 1914. No US women competed at the 1912 games.

The 1916 games were cancelled during World War I making the 1920 games in Belgium the first to host American women since 1904. American women competed in swimming, diving, and figure skating events. Aileen Riggin, the youngest athlete on the US team at age 14, won a gold medal in diving. Ethelda Bleibtrey became the first American woman to win an Olympic swimming title and also the first woman, from any country, to win three gold medals.

Competitive Women Meet Resistance

Women’s athletics enjoyed immense popularity in the U.S. during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. By 1920, 22% of colleges and universities offered women’s athletic programs, and secondary school physical education was compulsory in nearly every state. A growing number of club teams and company-sponsored teams widened women’s sports opportunities.

As women’s competitive opportunities expanded, women athletes met an unanticipated source of resistance. In 1922 the National Women’s Track Athletic Association petitioned the AAU to sanction women’s events. The AAU voted to become the governing body for women’s track and field; however, the women who ran girls and women’s physical education programs in schools and colleges strongly protested.

Women physical education teachers, who predominantly taught girls and women, deeply objected to women’s competitive sports. Their philosophy of women’s athletics emphasized physical fitness and mass participation. Competition, they argued, was counterproductive. It funneled resources to a small number of elite athletes at the expense of scores of girls and women who would reap health benefits from mass participation. Moreover, competition made games less fun, discouraging more girls. Starting in the 1930s, women’s competitive sports were gradually all but eliminated at the collegiate level to be replaced with game days and exercise classes.

Falling Behind in the Medal Count

The dearth of women’s collegiate athletic programs narrowed the US Olympic team’s pool of potential athletes even as the IOC increased the number of women’s sports. Women turned to club and company-sponsored teams as outlets. However, the lack of access to skilled coaching and higher level training adversely affected women’s results in international competitions, including the Olympics.

Wilma Rudolph at the finish line during 50 yard dash track meet in Madison Square Garden in 1961.

The major exception was women athletes from historically black colleges. While elite, pre-dominantly white universities had eliminated women’s athletic programs, many historically black colleges retained them. The most prolific program arose at Tennessee State University where Ed Temple served as head women's track coach from 1950 to 1994. During his tenure, forty members of his famed Tigerbelle teams represented Tennessee State University in Olympic competition, winning a total of 23 medals (13 Gold, 6 Silver, and 4 Bronze). Temple coached famed Olympian Wilma Rudolph to three gold medals at the 1960 Rome Olympics.

Sports governing bodies grew increasingly concerned through the 1950s, 60s, and 70s over US women’s weak showing against Eastern bloc countries. The Olympics had become a Cold War battlefield, and the East was winning. While Eastern bloc countries doped athletes to improve conditioning, they also created state-run training programs designed to produce winners. US women, lacking an organized system of training and support, were simply out-matched in many events.

Title IX Evens the Playing Field

The tide changed in 1972. Title IX mandated that girls have equal opportunity for sports participation as boys. It immediately expanded the number of competitive slots for girls and women, facilitating their development into elite athletes. Before Title IX, fewer than 30,000 women were collegiate athletes, rising to 190,000 in 2012. Many of them, like star soccer forward Abby Wambach (University of Florida) and swimmer Natalie Coughlin (University of California, Berkeley), distinguished themselves and their alma maters in international competition.

Female Olympic athletes continue to make strides. The 2012 US team in London was the first to include more women than men. US women brought home 58 medals, to the men’s 45. Getting in the game is the first step to winning.

Barra, Allen. “Before and After Title IX: Women in Sports.” Accessed August 4, 2016.

Fuller, Linda K. Olympics access for women: athletes, organizers and sport journalists. In, Jackson, R. and T. McPhail, (Eds.), The Olympic movement and the mass media: past, present and future issues, Calgary: Hurford Enterprises, 4/9 – 4/18. 1987.

“Olympic Games | Britannica.com.” Accessed August 5, 2016.

Smith, Lissa. Nike Is a Goddess: The History of Women in Sports. Atlantic Monthly Press, 1999.

Woolum, Janet. Outstanding Women Athletes: Who They Are and How They Influenced Sports in America. Greenwood Publishing Group, 1998.