The First Women to Make Movies

Motion pictures began in the East in the 1890s, then settled in Southern California around 1910 where the sunny climate was perfect for filming. In these early years, across this country, in tiny towns and big cities, thousands of young women sat in darkened theaters, yearning to join the action on the screen. Some adventurous women were already proving they could write, direct, edit, and produce films. Many others wanted to be actresses; a few of those were superb swimmers or riders who would become the first stuntwomen and prove "the weaker sex" could perform surprising feats of action. They prevailed despite the Victorian constraints that still dictated women's behavior, morals, and aspirations. Science had declared women mentally and physically weaker; they had few financial rights, were excluded from education and professions, and the basic right to vote. However, a technological and cultural transformation was in motion in America and around the world. The advent of the suffrage movement, cars, and movie heroine role models gave women the means and motivation to reach for more. The years 1910-1920 were innovative, liberating, and exuberant.

"The Flickers" were considered trashy amusements, no more reputable than the the first storefront nickelodeons, named for the five-cent price of admission, or the immigrants and urban poor in the audience. But they were cheap, entertaining, and exciting; ideal places to get away from grim realities in working class neighborhoods. Movies became both a profitable business and socially influential. In addition to love stories, dramas, and action serials, moviegoers watched films promoting the vote for women, such as popular What 80 Million Women Want (1913).

For decades, women’s contributions to silent movies were mostly ignored until film historian Anthony Slide’s archival research in 1977 rescued them from oblivion. Movies hired people other businesses excluded—women and immigrants. In film studios, women’s jobs ranged from plaster-molders, set designers, and film editors to writers, directors, even production executives. “The simple fact that all the major serial stars of the silent era were female demonstrates the prominence of women at this time,” Slide wrote in Early Women Directors, “as opposed to the sound period when serial stars were men, and women were reduced to simpering and generally incompetent supporting roles.” But before sound arrived, “Of the 500 top silent screen performers, including both stars and below-the-title leading players, some 287 were women.”

In these changing times, cars gave women mobility and independence, which the action on movie screens encouraged. Racing or crashing cars were essential to movies, and stars like Mary Pickford assertively set the pace. Who could fail to be influenced by seeing America’s Sweetheart lean into the curve as she hit 50 miles an hour historian William Drew stated, “[I]t was the actresses, not the actors, who were shattering Victorian ideals of gender roles through their yen for driving fast cars."

Movies were glamorous and dangerous—films were turned out fast, without the nuisance of safety guidelines; someone thought up a car crash and had no idea if it would work until someone else tried it. At Pathé studios, for example, Louis Gasnier urged his writers: “Put the girl in danger.” They fulfilled that mission with vigor. From 1918 to 1919, 37 movie companies reported 1,052 “temporary injuries, 18 permanent and 3 fatalities.”

When few male actors or directors had their own production companies, Slide estimated from 1912 to 1920 women behind and in front of the camera formed more than 20 independent companies. Director Alice Guy Blaché, developed the narrative film as early as the 1890s and was the first to set up her own company in 1910. Director Lois Weber, who was as famous in her time as D. W. Griffith, did the same. Some men managed the companies, but to a great extent silent movie stardom was the realm of women. As Slide wrote, “Power was in the name, and the name was woman.”

In addition to Frances Marion (screenwriter), Edith Head (costume designer), and Dorothy Arzner (director), scores of other women worked behind the camera. Though their achievements have been documented, they are still not nearly as well known as they should be. Here are a few whose talents shaped the movies.

Alice Guy-Blaché. 1913.

Alice Guy Blaché, a preeminent director, writer, and producer is in a class by herself. After she had directed 400 films in France, 1896-1907, she came to America "to direct or supervise" the production of 354 more films, 1907-1920. She was the first person of either sex to make films on a regular basis, she built her own studio in 1912, and "she established the concept of the director as a separate entity in the filmmaking process."

Lois Weber. May 21, 1912.

Director Lois Weber, committed and determined, knowledgeable about all phases of production, wrote and directed films on serious subjects: capital punishment, prejudice, and poverty. In The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (1917), which advocated for access to birth control, one title crisply notes, "If the lawmakers had to bear children, they would change the law." She is credited with 137 films, many of them controversial, such as Hypocrites (1914). "The film caused riots at New York's Strand Theatre for its daring use of full nudity. Assured of a moral tale in an entertaining context, audiences quickly learned to spot Weber's trademark as well as they could Griffith's."

June Mathis circa 1920

In the early years of filmmaking, almost all scenario writers were women who wrote the subtitles for films. June Mathis was one of them. In her youth, she had performed on the stage before she found a way to break into the work she really wanted--screenwriting. When she joined Metro studios in 1918, she must have burst on the studio scene like a rocket flare. "As one of the first screenwriters to include details such as stage directions and physical settings in her work, Mathis saw scenarios as a way to make movies into more of an art form." In 1920, she headed Metro's scenario department, the first female executive at that studio. She is credited with discovering Rudolf Valentino. She wrote Camille (1921), Blood and Sand (1922), adapted Ben-Hur (1925). By this time, she was more than a writer. "Miss Mathis, responsible for the scenario of The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921) and for the casting of Rudolph Valentino, was one of the most important figures in the industry . . . A woman of indomitable strength and energy. . . " Kevin Brownlow wrote, noting Mathis' huge difficulties on Ben Hur. She scripted a half-dozen other films, but at the height of her career, she died of a heart attack.

Anita Loos, May 1920.

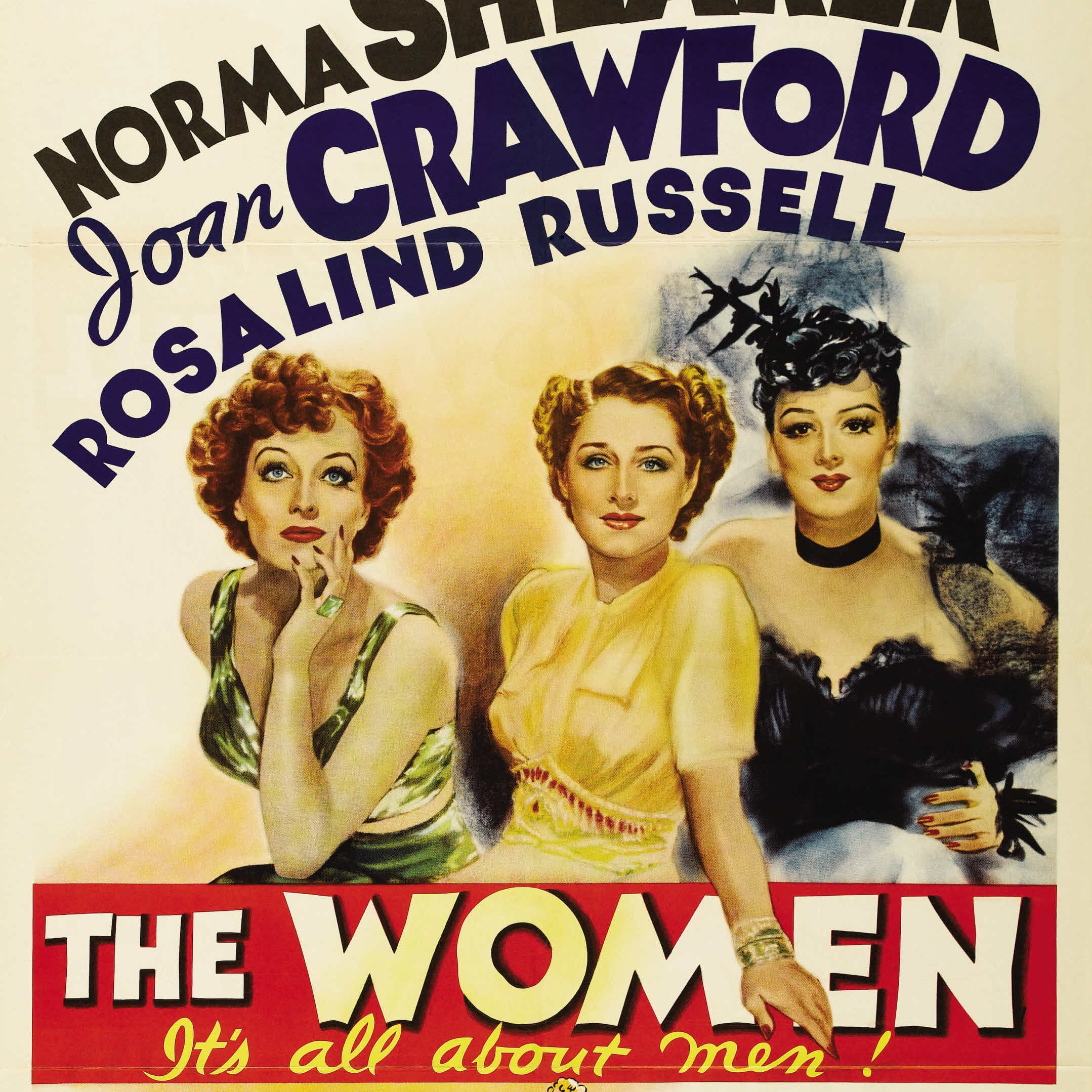

In 1911, Anita Loos sold a scenario to D.W. Griffith at the Biograph Company. She was witty, fresh, and brainy; she sharpened the craft of subtitling, just as June Mathis, Bess Meredyth, and the gifted Frances Marion, in their different ways, advanced the form. From 1912-1915, Loos churned out over a hundred scripts for two-reelers. Her "satire sprang not from a suppressed social conscience but from a bubbling creative sense of fun," Kevin Brownlow wrote. She wrote the titles for Griffith's Intolerance (1916), five scenarios for Douglas Fairbanks; her 1925 book, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, was a surprise hit. Unlike Weber, Loos was in sync with the 1920s. She made the passage to sound, writing scripts for San Francisco (1936) and The Women (1939), novels, plays, and memoirs well into the 1970s.

The rash, risky, high-spirited silent era vanished when sound arrived, but even before that, in the mid-1920s, careers for women behind the camera began closing down, and it was much harder in the studios' new departmental system to move up the ladder. Actress-stuntwomen were no longer stars; they became the stuntwomen who, without credit, doubled the few actresses in action roles.

In the early days, the movies had had an image problem. Women in production and as managers in theaters helped studios and theater owners convince the public that going to the movies or working in movies was respectable. “Women represented respectability” Slide wrote, but when the industry "became too successful and no longer needed to seek respectability, it could disregard . . . its female employees--no matter how talented they might be--and become a male-dominated business."

Mollie Gregory is the author is Women Who Run the Show: How a Brilliant and Creative New Generation of Women Stormed Hollywood and Stuntwomen: The Untold Hollywood Story.

Originally published in Volume 20 of A Different Point of View "Women in Early Film".

Acker, Ally. Reel Women, Pioneers of the Cinema 1896 to the Present. New York: Contimuum Publishing Co., 1991.

Brownlow, Kevin. The Parade's Gone By. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1968.

Hering, Dorothea B. “The Sensational Feats of Motion Picture Stars.” Munsey’s, 71, December 1920, 412-19.

Lahue, Kalton C. Bound and Gagged: The Story of the Silent Serials. New York: Castle Books/A.S. Barnes & Co., Inc., 1968.

Stamp, Shelley. Movie-Struck Girls: Women and Motion Picture Culture After the Nickelodeon. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000.

Slide, Anthony. Early Women Directors. New York: Da Capo Press, 1984.

Slide, Anthony. The Silent Feminists: America’s First Women Directors. London: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1996.

Scharff, Virginia. Taking the Wheel: Women and the Coming of the Motor Age. New York: The Free Press, 1991.