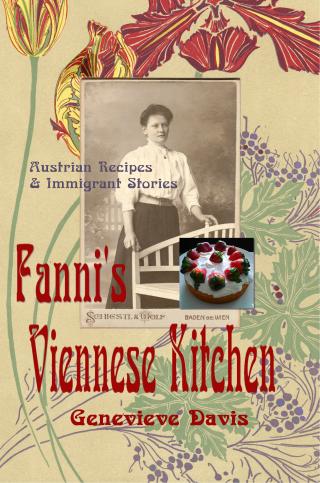

Fanni's Viennese Kitchen

Fanni and Johann

When my mother was a young teenager during the Great Depression, she was too embarrassed to bring her friends over to witness the homey scene taking place in the central dining room. Her father, Johann and their boarder Uncle Herman, both out-of-work, would be sitting on either side of the table in their sleeveless undershirts, smoking and reading the German-language newspaper. Her mother, Fanni, sat at the far end of the dining room table, opposite the front door, where she sprinkled clothes, knitted mittens, darned the family’s socks, mended clothes, embroidered pillow cases, and kept account books for the household. All the while they were sitting around the dining room table, they spoke to each other in their immigrant language—German. Apparently, my teenage mother never saw the glamorous people in movies acting like this. Ach du lieber!

Fanni was a cheerful, kind, hard-working gal, who made everyone feel good about themselves. I always saw her interact harmoniously with everyone, but apparently, she could put her foot down when she had to. Like one time, when a cop gave my mom a ticket for driving too fast in a construction zone in the dark at 4 am. She was going the speed limit. She burst into tears and hung her head over the steering wheel. Fanni leaned forward in the back seat and told the cop, “Shame on you! She has to drive us all the way to Baraboo for a funeral and you've made her so upset she can't drive!” He tore up the ticket. What else could he do?

Fanni's store in Vienna.

Another time, back when they lived in Vienna, there had been a bruhaha over her husband Johann, who, unbeknownst to Fanni, had put up the deed to her milk store as collateral for a friend. Fanni found out about it only when she lost the store. Ever after that, Johann had to sign his pay check over to Fanni. Nevertheless, from what I gather, they had an otherwise amicable relationship.

When the stock market crashed in 1929, Fanni, Johann, and their two girls came upon hard times in the Great Depression. Banks and businesses closed, people lost their savings, their homes and their jobs. Johann was soon laid off from his job at the bakery, because there weren’t even enough people with money to buy bread to keep him on.

Fanni's immigration papers

My grandmother Fanni had experienced so much hardship previously in Vienna during and following the Great War, that “she coped better than most during the Depression,” according to my mother. “If there was just a little, she already knew how to make do with it.” Here's how she did it with her cooking. Before breakfast, Fanni would walk to the bakery for day-old sweet rolls. Then she would come home and make farina or oatmeal, and that was breakfast.

At lunchtime, she would make Mehlspeise, out of flour, rice, noodles, or day-old bread. She added a little egg and milk and voila—lunch! These dishes were really yummy, like—French Toast, Crumbs of the Czar—called Kaiserschmarren in Austria, and Palatschinken or Crepes [see easy recipe below].

For dinner she served the beef bone-potato-carrot soup she had been cooking all day on the back of the stove, with semmeln rolls, that according to Mom “were shaped like a ‘behind.'” Rye bread spread with bacon grease and sliced cold cuts of meat rounded out the meal. Fanni made desserts for dinner, like jello, pudding, or more day-old sweet rolls.

All of these items were inexpensive. I remember she would cut a cross on the bottom of a loaf of bread before cutting it, as thanks for even having it. She told me that, when her husband was off in the war, she had to stand in breadlines all day in Vienna, with her children, for a crust of bread.

Fanni brought in cash, too, from the upstairs tenant, a lady who paid regular rent by doing sewing and alterations for those who could still afford it. Fanni also took in a boarder, Herman Signer, who was out of work, but had savings. She provided room and board, laundry and ironing. He remained with the family for 40 years. Herman was eligible for commodities, because unlike Fanni and Johann, he wasn't a home owner. Once a month he took the red coaster wagon to the supply depot for his ration of dry foodstuffs, which he then gave to Fanni. She made up the oatmeal and farina for breakfast. With the flour she made those Mehlspeise dishes. Nice!

Another way Fanni brought in cash was walking 20 blocks to clean houses in Washington Heights, where people lived in big homes. She got 10 cents for several hours work, but didn’t take the streetcar to get there, because that cost 5 cents and would have used up her wages. Fanni also worked for Dr. Hansen, who lived a couple of blocks away in apartment. He proved to be a valuable contact for the family later on. She did his laundry and ironing, picking it up and delivering it on foot, because they had no car. In fact, none of them, except my mother, ever learned how to drive.

Even though Johann was out of work, he was no slouch. He was a very nice man, too, according to everyone who knew him, although privately he suffered from PTSD from the war. According to my mom, he had terrible nightmares and a temper that made him break something and then go downstairs to his workshop and fix it. He contributed to the family by making their beautiful furniture from scrap wood, looking for work every day like it was a job and hiring himself out as a carpenter for food. When he did find some work, it was building a house, single handedly, for the next-door neighbours. He was paid in chickens, potatoes, carrots, parsley, and cash.

An elderly lady had given Fanni and Johann their mortgage on their house in 1929, before the crash. They must have missed some payments, because by 1933, when the Depression had been going on for four years, that lady wanted her $2,000 back and came to the house to get it several times, with her attorney in tow. “I want my money. I can’t live on what I have,” the old lady complained. Mom, who was a little girl at the time, was scared and confused and wondered, “Why is my mom so upset?”

That Dr. Hansen, the one Fanni did laundry for, told them about the FHA housing loan program. They saved their duplex by refinancing it with a government loan. Otherwise, they'd have been out on their ear, like the out-of-work guys who knocked at the back door, looking for food. Fanni was sympathetic and gave them a bowl of soup from the big pot she always kept on the back of the stove, and a piece of bread. Dr. Hansen also told them about the WPA Public Works program. There Johann found steady work for a time, laying out Milwaukee’s vast, beautiful gardens in Whitnall Park.

Fanni was instrumental in getting her family through the Depression. She kept her family's lives on an even keel with her housework: making soups and Mehlspiese, mending clothes and sheets, darning socks, knitting mittens, and keeping the household books. That was in her free time, because, she also cleaned houses and took in laundry and collected rents. She had a valuable contact in her employer Dr. Hanson, who helped them learn about the FHA and the WPA. Fanni, with her experiences surviving the Great War, provided for her family of four with her hands-on, creative approach to making ends meet.

Palatschinken (also called Crepes or Omletten)

Codified by Mom

The yummy Viennese way to make a meal, with flour and egg and a little milk. Grandma called them “roll ups.”

Ingredients:

- 4 cups flour

- 3 to 4 eggs

- 3 cups milk, or more for thin crepes

- a little salt – 1 tsp.

- butter or oil to cook the crepes in

- jelly

- powdered sugar

Instructions:

Mix egg, milk, flour and salt until the consistency of cream. Drop this liquidy batter to make one crepe at a time on a hot skillet coated with butter or oil. Spread with jelly and roll up. Then, sprinkle with powdered sugar. Fanni made these one by one and served it to the lucky one whose turn was next! Alternatively, you can make them all ahead, keep them warm in a slow oven, and serve them all at the same time.

Genevieve Davis is the author of Fanni's Viennese Kitchen, a collection of authentic Austrian recipes and stories of immigrant life in America. This article is excerpted from the book, which is available directly from the author at www.october7thstudio.com or from Amazon.

Davis is also the author of Secret Life, Secret Death, the story of a young mother who fell into crime with the Mob in the Roaring 20's. And she produced and directed the docudrama film, Secret Life, Secret Death. Both the book and the film are available from her website www.october7thstudio.com where you can read the first chapter of the book and see clips from the film.