Dorothea Dix and Cornelia Hancock

On April 14, 1861, Fort Sumter fell—the beginning of four years of brutal war. President Lincoln immediately called for 75,000 militia volunteers to put down what he described as a state of insurrection. The response was overwhelming. Tens of thousands of men enlisted. But Lincoln also had volunteers from a source he never expected and never asked for: women who wanted to serve their country.

Thousands of women volunteered as nurses. By one estimate, more than twenty thousand women served as nurses on the Union side during the war, not including an unknown number of women who volunteered on an ad hoc basis.

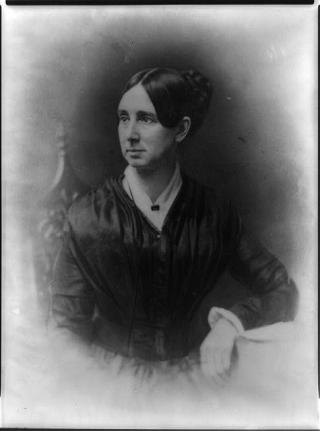

Dorothea Dix

The first woman to volunteer was Dorothea Dix, a fifty-nine-year-old reformer who had spent the twenty years prior to the war fighting to improve the treatment of prisoners, paupers, and the mentally ill.

Dix was visiting friends in Trenton, New Jersey when she heard the news that Sumter had fallen. She immediately packed her bags and left that afternoon for Washington. When she arrived in Washington on the evening of April 19, the city was on high alert. Pickets guarded public buildings and bridges. Soldiers were billeted at the White House in anticipation of a Confederate attack before morning. A less determined woman might have hesitated, but Dix went directly to the White House.

If any other woman had appeared at the White House unannounced that night, she might have been turned away. But Dix was preceded by her well-earned reputation as a humanitarian, crusader, lobbyist, and, most importantly, as a woman who got things done. She was used to working with powerful politicians and they were used to working with her. Even with the threat of the Confederate Army at the door, she received a warm welcome and a fair hearing for a revolutionary proposal: she volunteered her services to create an army corps of female nurses to care for wounded soldiers. Four days later, Secretary of War Simon Cameron accepted her proposal. In June, she was appointed as the superintendent of women nurses for the Union Army—the first federal executive position to be held by a woman.

Dix's proposal required a fundamental change in the Army's practices regarding nursing. Nursing wasn't yet a profession and it wasn’t something respectable women did. Before the Civil War, convalescent enlisted men who were not yet able to return to their military duties provided any nursing the Army's Medical Bureau needed. Left to its own devices, the Army would have done nothing to change this.

Dix envisioned a corps of female nurses modeled on the women who served with Florence Nightingale in the Crimea in 1854. She had a very clear idea of what she wanted them to look like. Only women between the ages of thirty or thirty-five and fifty would be accepted. “Neatness, order, sobriety and industry” were required; “matronly persons of experience, good conduct or superior education” were preferred.

Possibly the most controversial of her requirements was the demand that nurses were to present a plain appearance, a dictum often interpreted, then and now, to mean that Dix believed nurses should be homely women. The wording in Circular No. 8—the official statement of requirements for army nurses that Dix published on July 24, 1862, in conjunction with Surgeon General William Hammond—does not support that interpretation. What is clear is that they were to wear brown, gray, or black dresses: practical choices given the inevitable exposure to blood, pus, vomit, and other filth in a hospital of that day and the heroic efforts required to do laundry in the nineteenth century. Bows, curls, jewelry, and especially hoop skirts and crinolines were forbidden. Again, a practical requirement. Hospitals were crowded and the aisles were too narrow for women in fashionably wide skirts to walk through.

Dix turned away able applicants because she thought they were too young, attractive, or frivolous. Many of those she rejected found other ways to serve.

Cornelia Hancock

Twenty-three-year-old Cornelia Hancock, for instance, was preparing to board the train to Gettysburg with a number of older women who had already been approved as Dix nurses when "Dragon" Dix herself appeared on the scene to inspect the prospective nurses. She pronounced all the nurses suitable except for Hancock, whom she objected to on the grounds of her “youth and rosy cheeks.” Hancock simply boarded the train while her companions argued with Dix. When she reached Gettysburg, three days after the battle, the need for nurses was so great that no one worried about her age or appearance. Too inexperienced to actually nurse, on that first day she went from wounded soldier to wounded soldier, paper, pencil, and stamps in hand, and spent the night writing farewell letters from soldiers to their families and friends. When wagons of provisions began to arrive, Hancock helped herself to bread and jelly and divided the loaves into portions that could be swallowed by weak and wounded men.

She quickly became accustomed to the realities of the battlefield. On her second day in the field she wrote in a letter to a cousin. "I do not mind the sight of blood, have seen limbs taken off and was not sick at all." In fact, Hancock proved to be such a dedicated nurse that the wounded soldiers of Third Division Second Army Corps presented her with a silver medal inscribed Testimonial of regard for ministrations of mercy to the wounded soldiers at Gettysburg, Pa. – July 1863. (She also had a dance tune named after her, the Hancock Gallop—a tribute that I suspect none of Dix's middle-aged matrons received from the soldiers under their care.)

Hancock worked as a nurse for the rest of the war, tending the wounded after the battles of the Wilderness, Fredericksburg, Port Royal, White House Landing, City Point and Petersburg. She was one of the first Union nurses to arrive in Richmond, Virginia after its capture on April 3, 1865.

Like many other nurses, after the war, Hancock devoted her life to reform. She helped found a freedman’s school in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, where she taught ex-slaves for a decade. (At one point those who objected to the concept of education for black children riddled the schoolhouse with fifty bullets.) When she moved back north to Philadelphia, she helped found the Children's Aid Society of Pennsylvania.

Hancock became a posthumous best-selling author in 1937, when her charming and insightful letters from the battlefield were published under the title South After Gettysburg, now available under the title Letters of a Civil War Nurse. (Well worth the read if you are interested in Civil War nurses or daily life in a Union army camp behind the lines).

United States Sanitary Commission Lodge in Alexandrai, VA

As for Dix, she was grateful when the war ended. During the four years of the war, she butted heads with officialdom, quarreled with military surgeons and the men who ran the United States Sanitary Commission (a volunteer organization dedicated to improving sanitary and moral conditions in the Union army), lost weight she could not afford to lose, and suffered from a variety of ailments, including malaria and lung problems, but she never faltered. Discharged along with her nurses on September 11, 1865, she turned herself into a one-woman relief agency, putting in long days calling in small favors from her vast network of contacts. Her favorite task was helping disabled nurses and soldiers find their way home. She also helped soldiers collect back pay, found food and clothing for poor veterans and their families, searched for homes for war orphans, and occasionally used her contacts to help families locate soldiers missing in action.

Dix's corps of nurses was the largest and most official group of women who worked as nurses for the Union during the war, but it wasn't the only path to nursing. The United States Sanitary Commission maintained and staffed field hospitals and transport ships, as did its St. Louis-based rival, the Western Sanitary Commission and various unaffiliated ladies' aid societies. Some women were commissioned as nurses in the same local militia unit in which their husbands served—an informal process in no way officially sanctioned by US military. Others, like Hancock stepped outside the system altogether and nursed without official sanction from anyone.

Some were inspired by Nightingale’s Notes on Nursing. Some were called to nurse by religious zeal—volunteers for the United States Christian Commission were as concerned with saving soldiers' souls as with healing their bodies; others were driven by the financial need caused by a husband’s absence in the war. But many, perhaps most volunteered because of the same desire for patriotic action that led young men to enlist in the first rush of enthusiasm for the war. Louisa May Alcott summed up that desire, writing in her diary soon after the fall of Fort Sumter, “I long to be a man; but as I can’t fight, I will content myself with working for those who can.”