The Dangerous Experiment

Colleges for women in the United States, founded in the second half of the 19th century, began as dangerous experiments. Founders wanted to offer young women—typically, and sometimes exclusively, Christian, white, and from the middle or upper classes—higher learning, such as that provided by Yale. But they feared accompanying risks. College-grade education itself was a given, thus initial planners turned elsewhere. They sought to shield female collegians through the college’s physical environment—its architecture and campus plan. The early buildings and landscapes of the Eastern women’s colleges once known as the Seven Sisters enable us to see both hopes and fears at the time of their creation.

The dangers founders imagined focused on the fear that higher education might unhinge women. These men worried that the rigors of Greek, Latin, mathematics, and life away from the familial circle might turn women away from traditional femininity. Female collegians might either imitate men or lose their innocence and virtue, both abominations to right-thinking Americans in the mid-19th century.

The men’s colleges that founders knew had assumed a particular form by the 19th century. Whether built piece-meal as at Yale or from a comprehensive plan as at University of Virginia, male colleges were “academical villages.” Men recited, studied, prayed, slept, and ate in a variety of structures. The buildings we call dormitories, represented on the Yale campus by Connecticut Hall, were generally 3-4 story stretches of rooms, reached through four entries, two on a side. On college books were rather strenuous rules, enforced by a faculty of tutors and professors; but because men could enter their rooms through stairways without passing a central observation point and could move around from college to village, from residence hall to chapel, free from supervisory eye, they had the freedom to develop a separate and powerful subculture, “college life.”

Believing that young women should have no such freedom, early founders initially designed colleges that secluded them and set them within a single building where their every movement could be observed and controlled. For this they had a precedent, the female seminary. They looked especially at Mount Holyoke in Western Massachusetts, founded in 1837.

The female seminary was not a college, but rather a later version of the academy, an 18th century creation offering modern languages, science, history, and vocational subjects at a level bridging secondary school and junior college. Academies drew both local youth and those of surrounding farms and villages and thus often provided boarding. In the early nineteenth century, certain academies were founded for girls with a new, serious intent to prepare them for teaching. The name seminary in the 19th century expressed vocational emphasis (retained today in schools to train ministers) and was often adopted by female academies to train teachers.

Mount Holyoke Seminary’s founder, Mary Lyon, imagined offering the English curriculum and changing the consciousness of women students. She wanted to bring order into their lives and allow them to move outside the private claims of the family circle. To do this, she drew on a building precedent of her day and designed her seminary after the model of the new mental asylum.

19th century reformers focused on mental illness believed that if you separated those who were disordered in their minds and placed them in a structure of external order, they would internalize the rules to create an inner psychic order. Mount Holyoke Seminary carried the same assumptions. Its rules were strict: between the bell that awakened students at 5:00 am and required their lights to be off at 9:00 pm, students followed a prescribed schedule of recitations, study, prayer, and housework. Living along a corridor with their teachers, they confessed each week to a specific teacher regarding how they had followed or broken the rules. The school’s design both expressed and enforced these rules. Everything happened in a single building, an enormous house for over 100 students and teachers. In its complete provision for living, learning, and working, Mount Holyoke held no places for retreat, no interstices for freedom.

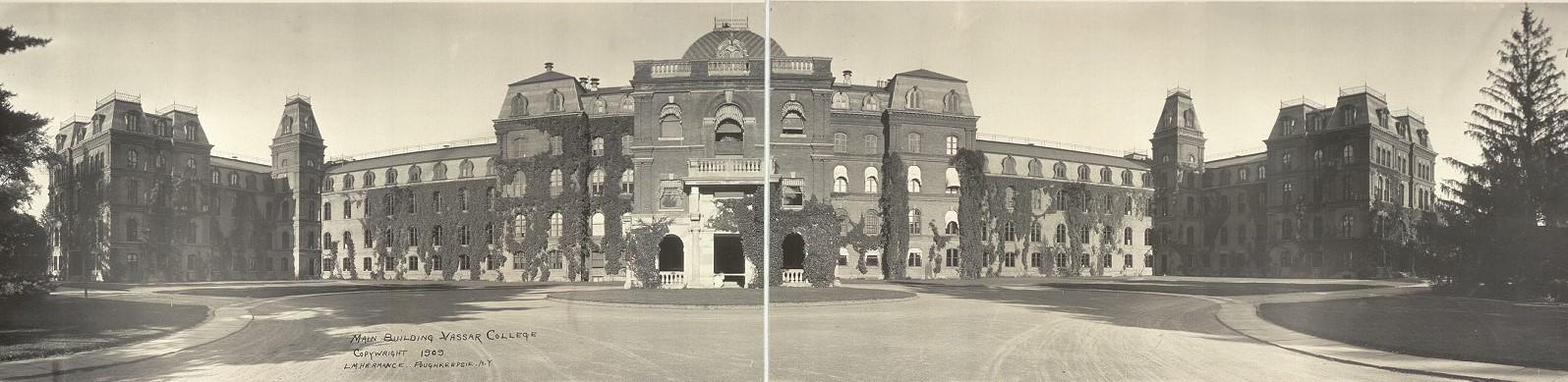

In 1861, when Poughkeepsie brewer Matthew Vassar endowed Vassar College for women, “to be to them what Harvard and Yale are to young men,” he founded a real college, with an undiluted liberal arts course and a full college faculty. However, he hedged his bets and linked to it the female seminary’s plan of governance and building form. He took the advice of the former male head of such a school, who assumed the seminary system was the best way to protect the young women offered the liberal arts. Thus, the first women to attend a college equal to the best male schools did so in buildings and landscapes that had little to do with the forms of men’s colleges.

As Vassar College arose in brick and mortar, it was as an immense seminary building, designed by one of America's foremost hospital architects, James Renwick, Jr. In keeping with the newest approaches of mental asylums, Vassar College was placed on a picturesque site in the country. In a building four and five stories high and 1/5 of a mile long, the largest building in America when it was built, Renwick essentially copied the plan of Mount Holyoke, now for four hundred students and faculty. The central pavilion functioned as Mount Holyoke's principal floor, housing all the public spaces. One entered through ceremonial steps to find reception hall, parlor, dining room, chapel, museums for science and art, library, president's quarters, and classrooms. The male college faculty lived with their families in apartments in the end pavilions. Along the corridor, students lived with their teachers, the young female assistants of the professors. These women supervised their charges under the direction of a Lady Principal, who had the responsibility for creating and maintaining the seminary system, thereby attempting to control students as firmly as did Mount Holyoke. Vassar's Main Building is a fitting testimonial to the hopes and fears of offering higher learning to women.

Vassar's system and its building seemed initially to be the correct solution to the problem of offering women higher learning and keeping them within the protective bonds of womanhood. Without really looking closely at its workings or considering alternatives, Henry Fowle Durant planned Wellesley College as a close copy of Vassar. In 1875, when Wellesley opened, it, too, offered women the liberal arts linked to the seminary system of governance and building.

The planners of Smith College, however, decided that the seminary system failed to protect the femininity of young female collegians. Vassar in 1865 was not Mount Holyoke in 1837. Its students of varying ages from all over the divided nation had no intention of submitting their wills to a Lady Principal. On their corridors, they began to develop a collective culture that had much in common with their brothers at Yale. They saw the rules as external and sought to evade them. They reveled in their private friendships in the suites along the corridor. They formed alliances with those professors who also rebelled against administrative authority. And they began to develop curious customs and traditions that gave collective expression to their life and questioned conventional notions of femininity. Within Vassar’s walls appeared college life.

The shapers of Smith perceived the effects of Mount Holyoke to be as objectionable as those of Vassar. Although Sophia Smith endowed the women's college, its plan was the combined work of her minister and advisor, John Morton Greene, and Amherst College professors aiding him. From the outset of Greene's conversations with Sophia Smith, he was clear that Smith College should differ from Vassar and Mount Holyoke is several critical ways. Following new approaches to treating the mentally ill outside of asylums, Smith chose not to put its students into one large building, but rather build several “cottages.” And instead of the isolated, village or rural site, Smith should be located in the town of Northampton. Together these two features would allow students to remain in touch with the social life of the town and keep them, as Greene put it, “free from the affected, unsocial, visionary notions which fill the minds of some who graduate at our girls' schools.”

Men such as Greene perceived the potential new danger of a women's college, such as Vassar. Rather than protecting women and conventional femininity, it could foster intense female friendship and generate strong-minded women. The solution they found was to educate women in college but keep them symbolically at home. In 1875 Smith opened with a Victorian Gothic main building for instruction, close to the center of Northampton; a house for the president; and a cottage, soon to be followed by others, where students lived in quasi-familial settings. Female students were brought into daily contact with men as president and faculty. The college built no chapel or library to encourage students to enter into the life of the town.

The origins of Radcliffe College lay in Harvard’s refusal to accept women students. In 1879, a new venture opened in Cambridge, the “Harvard Annex,” incorporated three years later as The Society for the Collegiate Instruction of Women. From the outset, Harvard professors taught women students the courses that they offered to men in the Yard, but in rented rooms in a house in Cambridge. The Annex's founders disliked the seminary system as they had seen it at Wellesley College so intensely that they went beyond Smith. Radcliffe's initial plan had no provision for living. Young women offered the chance to study under Harvard professors under the separate auspices of the Annex simply lived at home, if they were from Cambridge or Boston; if they came from elsewhere, they boarded with Cambridge families. This eliminated the possibility that they would be affected by living together under one roof or several. In 1894, with an endowment and a formal relation to Harvard, this institution emerged as a coordinate college, and took the name Radcliffe. Working with Columbia, a more encouraging university in midtown New York City, Barnard College initially followed Radcliffe’s implicit example.

Bryn Mawr College began much like Smith. In 1885 when it arose in a suburb outside Philadelphia, its Quaker founder and the group of men whom he made trustees initially copied Smith's plan of academic building and cottages exactly. In time, however, Bryn Mawr broke the mold, bringing to an end the distinctive forms of early women’s colleges.

As Bryn Mawr’s first dean, M. Carey Thomas helped develop a college and graduate school for women modeled after the rigors of Johns Hopkins University. In 1894, she became Bryn Mawr's second president, a position she held until 1922. Thomas wanted buildings that carried no symbolic suggestions about the gender of the student body. An elitist (and racist), she admired the English universities Oxford and Cambridge and loved the theatrical style of Jacobean architecture. When Bryn Mawr began to build under her influence, it took form as quadrangles, one of the earliest and most elegant compositions of what has come to be called College Gothic.

Bryn Mawr was the critical breakthrough in the building history of women's colleges, ending a way of thinking focused on the dangers of offering women higher education. Before Bryn Mawr’s architectural reinvention, women's colleges built distinctive structures to mark their intention to protect young women receiving higher learning. After the creation of the quadrangles at Bryn Mawr, buildings at the women's colleges began to speak frankly of the promises rather than the risks of higher education for women.

The new physical forms that women’s colleges took confirmed what students had always known to be true. Earlier architectural experiments had never worked. Whatever founders’ intentions regarding buildings and landscapes, young women in these settings found ways to create a robust college life that bred independence from the established cultural norms of femininity. This, coupled with formal education, helped open the way for many women’s college graduates to enter the public arenas of the professions, politics, and reform—and to open their alma maters to broader reaches of American womanhood.

Dr. Helen Horowitz is the Sydenham Clark Parsons Professor Emerita of History and Professor Emerita of American Studies at Smith College and the author of Alma Mater: Design and Experience in the Women's Colleges from Their Nineteenth Century Beginnings to the 1930s. Her book is available for purchase on Amazon and the University of Massachusetts Press.