"Charity is Ever Kind"

On April 12, 1861, America officially entered into a Civil War, years in the making. This war would transform millions of lives and completely change the country as a whole. With the issuing of the DC Emancipation Act and the Emancipation Proclamation, millions of enslaved people gained their freedom, and thousands of formerly enslaved people, also known as “contrabands,” found refuge and freedom in and around the District. With an increase of refugees around the nation’s capital came a need to establish relief associations that would provide food, shelter, clothing, jobs, and education to the newly emancipated residents. African American women were instrumental in the organization and operation of contraband relief organizations. Through the invaluable work of African American women, including Elizabeth Keckly, Harriet Jacobs, and Mary Dines, the city of Washington, DC and its new residents received much needed relief and support to help assimilate them to their newfound freedom.

In the first year of the Civil War, Union General Benjamin Butler used the term “contraband of war,” to describe escaped enslaved people who found refuge at Fort Monroe, Virginia. This was the first time “contraband” had been used in regard to people, and the word spread throughout the country to describe those who escaped enslavement by crossing Union lines. Although the term became popular, describing enslaved people as an “illegal” item taken in war, he reduced enslaved people’s humanity to property.

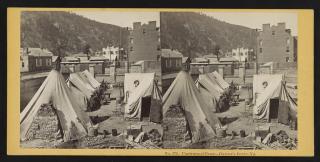

Over the course of the war, thousands of people fled their enslavers, and found their freedom within encampments. “Contraband camps”—temporary encampment neighborhoods inhabited by contrabands—increased exponentially in population. Living conditions in these camps were abysmal. Tents provided poor shelter from the elements while the constant threat of disease was deadly and demoralizing. Women in Washington DC and surrounding areas noticed a demand for relief aids in order to assist those in need.

Though she is most remembered for her role as Mary Lincoln’s dressmaker, Elizabeth Keckly was a prominent DC resident and a strong supporter of contraband relief societies. Keckly was born into enslavement in Virginia around the year 1818. In 1855 she purchased her and her son’s freedom for $1,200 (about $32,000 in 2017). After gaining freedom, she and her son moved to Washington, DC where she established a dressmaking business. Upon seeing the conditions of the contraband camps, Keckly made it her mission to help people living in the contraband camps. She went to church and suggested establishing a group to aid the newly-free men, women, and children. The Contraband Relief Association was established two weeks later at her recommendation with forty working members.

Elizabeth Keckly circa 1870 (Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Elizabeth Keckly also used her connections in Washington’s elite society to generate funds for these relief associations. She and Mary Lincoln were close friends and, while traveling in New York in September 1862, Keckly mentioned her contraband relief ideas to the First Lady. Lincoln was willing to help and gave her $200 (about $5,000 in 2017) to include in the funds for contraband relief efforts. Lincoln included a letter to the President stating that “contrabands in W[ashington] are suffering intensely… Many dying of want,” therefore she had given Keckly “the privilege of investing $200, in bed covering[s.]” As the First Lady described the dire conditions in which people were living, she stated that the money she gave to the Contraband Relief Aid was worthwhile because “the cause of humanity requires it.” It is clear that she empathized with the formerly enslaved residents as human beings and recognized the importance of basic necessities like bedding.

Portrait of Harriet Jacobs

Not only were contraband camps established in Washington DC, but neighboring cities, including Alexandria, Virginia, also experienced an influx of formerly enslaved people in need of aid. Harriet ‘Linda’ Jacobs and Julia Wilbur worked in both DC and Alexandria providing relief within contraband camps. Jacobs was born into slavery and spent the first part of her life serving a cruel master in Edenton, North Carolina. Jacobs was able to escape enslavement in 1835, and, although it took years, she was able to settle as a free woman in New York. Later, she moved to Washington, DC where she met Julia Wilbur, a Quaker and abolitionist. Through their friendship and hard work, Jacobs and Wilbur worked to provide formerly enslaved people with suitable housing, especially during the winter months. In early March 1863, the duo was tasked with providing housing for people in freedmen’s homes and hiring employees to take care of those in need. They also organized sewing societies to alleviate the work and stress put on the leaders of the organizations; the more people working and helping, the more aid could be provided.

In the camps, Wilbur and Jacobs witnessed “a sight & learned facts that make us sick at heart.” One incident involved witnessing a naked African American man exiting a shower and bath house, where he was leered at by Union troops, an act which caused Jacobs and Wilbur to wonder how African American women were treated. Wilbur stated, “I walked towards these [soldiers] & asked if they were Union soldiers? ‘Oh yes,’ & are you kept here to do such work on this? I am told that women & stripped & showered there too. ‘Oh! We never shower white women.’ I said color had nothing to do with it, they were women. Said one, ‘They are not women, we don’t call them women’, I said, they are more women than you are a man…’ Mrs. J. walked away when she heard the upstart orderly say “They are not women” for she feared she might say something & be arrested.” The degradation of African American women, and the unwillingness of the soldiers to consider women of color to be women, is just one example of the gendered and racialized mistreatment of women in freedmen encampments.

In 1865, the Freedmen’s Bureau, a governmentally appointed relief organization, began to provide aid to contraband camps as well. Unfortunately, women in the camps became dependent on the Freedmen’s Bureau due to unequal employment prospects. While the Bureau would find employment for “able bodied” freed men, women were denied these same opportunities. 58-year-old Ann Greshen was deemed unable to learn to provide for herself and was denied the money she had earned while working because the bureau viewed her to be too old and frail to have completed any work by herself. Greshen had no choice but to depend on the Freedmen’s Bureau in order to meet her most basic needs. This forced dependency on the Bureau applied to thousands of women, including in the South during Reconstruction. During the Civil War, African American freed women were viewed as “able-bodied,” and were hired to serve as cooks, laundresses, and aids in hospitals. However, those who did not find jobs as laborers and instead worked in fields or had been split from their families were considered destitute. Through this shift from providing women with work to forcing them to depend on the government, the Freedmen’s Bureau forced women to become dependent on men.

Along with this blatant discrimination, unmarried women were also denied government support because it would “promote promiscuous intermingling.” It was thought that government aid would encourage women to remain unmarried. Through the denial of relief to single women, the Freedmen’s Bureau attempted to create family units within the camps. This denial forced women to marry in order to have support yet kept them financially dependent on their spouse. Once married, women who had worked in domestic roles, caring for children and elderly relatives, found themselves without time to work outside the home. Women who escaped enslavement were aware that irate former enslavers would attempt to re-enslave them under the pretense of hiring them for work. If women refused to return to plantation labor, they could be sent to prison under false charges. One Freedmen’s Aid reformer who visited a Washington DC women’s prison found that many “colored women [had been] placed [in jail] by their former owners for trivial offenses, the real cause being that of leaving them.” For women living in contraband camps and in a post- Civil War world, life was full of uncertainty and danger.

Residents within the contraband camps worked hard to provide aid and education, despite the rampant disease and mistreatment. Mary Dines escaped along the Underground Railroad, hiding under straw in a hay wagon that transported her out of Maryland and into Washington DC. When the Civil War broke out, Dines moved to a contraband camp located on 7th Street in the city. Dines recalled the many visitors that came to the contraband camp, both white and African American, to teach and worship with people living in the encampments. She was a teacher and focused on educating both children and adults. Dines used cards printed with scripture from the Bible to teach her pupils to read. Soon, her students were able to “read whole verses in a very short time.” Dines, like Keckly and Jacobs, saw the importance of education not only for children but also for adults. Because she was literate, she also became the principal letter writer for those who were unable to read and write. Not only were women coming into camps to help educate free people, but women in the camps were also working toward educating both the young and old within the community.

Women, especially African American women, were critically important in the creation and operation of contraband relief societies. Through the aid provided and the efforts of Elizabeth Keckly, Harriet Jacobs, and Mary Dines, formerly enslaved people made the nation’s capital and the surrounding areas their home and transitioned into lives as free men and women. Though the transition from slavery to freedom was far from smooth, charitable efforts directed by women shaped African American life in the nineteenth century. African American women played a central role in organizing contraband relief aid and, without their efforts, people adjusting to a life of freedom would not have received the attention and care that they needed and deserved.

“Alexandria During The Civil War: First Person Accounts.” Accessed April 3, 2018.

Downs, Jim. Sick from Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Fleischner, Jennifer. Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Keckly: The Remarkable Story of the Friendship between a First Lady and a Former Slave. New York: Broadway Books, 2003.

“Harriet A. Jacobs (Harriet Ann), 1813-1897.” Accessed May 1, 2018.

Jacobs, Harriet A., and R. J. Ellis. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

“JuliaWilburDiary1860to1866.Pdf.” Accessed April 3, 2018.

Keckley, Elizabeth. Behind the Scenes, or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House. New York: G.W. Carleton & Co., publishers, 1868.

Manning, Chandra. Troubled Refuge: Struggling For Freedom in the Civil War. First edition. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2016.

———. An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle over Equality in Washington, D.C. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

“Unlikely Friends.” National Women’s History Museum. Accessed April 3, 2018.

Washington, John E. They Knew Lincoln. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc, 1942.

Asch, Chris Myers, and George Derek Musgrove. Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

“Benjamin F. Butler.” Civil War Trust, December 19, 2008.

Bentley, George R. “A History of the Freedmen’s Bureau.” University of Pennsylvania, 1955.

Cimbala, Paul A. The Freedmen’s Bureau: Reconstructing the American South after the Civil War. Original ed. Anvil Series (Huntington, N.Y.). Malabar, Fla: Krieger Pub, 2005.

“Contraband Historical Society-Hampton Roads, VA.” Accessed January 31, 2018.

“Contraband Hospital and School.” Accessed April 2, 2018.

“District of Columbia, Freedmen’s Bureau Field Office Records, 1863-1872.

Faulkner, Carol. Women’s Radical Reconstruction: The Freedmen’s Aid Movement. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004.

Fitzpatrick, Sandra, and Maria R. Goodwin. The Guide to Black Washington: Places and Events of Historical and Cultural Significance in the Nation’s Capital. Rev. ed. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1999.

Forbes, Ella. African American Women during the Civil War. Studies in African American History and Culture. New York: Garland, 1998.

“Fugitive Slave Acts - Black History - HISTORY.Com.” Accessed January 30, 2018.

“Fugitive Slave Acts Video - Fugitive Slave Acts.” HISTORY.com. Accessed March 31, 2018.

Furgurson, Ernest B. Freedom Rising: Washington in the Civil War. 1st Vintage Civil War Library ed. Vintage Civil War Library. New York: Vintage Books, 2005.

“General Butler and the Contraband of War.” The New York Times, June 2, 1861, sec. Archives.

Gerteis, Louis S. From Contraband to Freedman: Federal Policy toward Southern Blacks, 1861-1865. Contributions in American History, no. 29. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1973.

Haggard, Dixie Ray. African Americans in the Nineteenth Century: People and Perspectives. ABC-CLIO, 2010.

Harrison, Robert. Washington during Civil War and Reconstruction: Race and Radicalism. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Nicolay, John George, and John Hay. Abraham Lincoln: A History. Century Company, 1914.

Sterling, Dorothy. We Are Your Sisters: Black Women in the Nineteenth Century. W. W. Norton & Company, 1984.

SunPOTOMAC, Correspondence of the Baltimore. “Deplorable Condition of Freedmen in the District--Relief Wanted, but No Work--Germans and the Police--John Mitchell--Amnesty Pardons--Fatal Affair--A Citizen Older than the City--Real Estate Sale--Criminal Court--Alexandria, and Georgetown Matters.” The Sun (1837-1992); Baltimore, Md. October 27, 1865.

“Temporary Aid for the Freedmen.” New York Times. 1865.

“Their . . . Bedding Is Wet Their Floors Are Damp.” National Archives, August 15, 2016.

William B. Eames. “First Colored Church.” Howard University, November 19, 1863. Howard University Moorland- Spingarn Research Center.

Winkle, Kenneth J. Lincoln’s Citadel: The Civil War in Washington, DC. First edition. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2013.