Marsha P. Johnson

Marsha P. Johnson was one of the most prominent figures of the gay rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s in New York City. Always sporting a smile, Johnson was an important advocate for homeless LGBTQ+ youth, those effected by H.I.V. and AIDS, and gay and transgender rights.

Marsha P. Johnson was born on August 24, 1945, in Elizabeth, New Jersey. Assigned male at birth, Johnson grew up in an African American, working-class family. She was the fifth of seven children born to Malcolm Michaels Sr. and Alberta Claiborne. Johnson’s father worked on the General Motors Assembly Line in Linden, NJ and her mother was a housekeeper. Johnson grew up in a religious family and began attending Mount Teman African Methodist Episcopal Church as a child; she remained a practicing Christian for the rest of her life. Johnson enjoyed wearing clothes made for women and wore dresses starting at age five. Even though these clothes reflected her sense of self, she felt pressured to stop due to other children’s bullying and experiencing a sexual assault at the hands of a 13-year-old-boy. Immediately after graduating from Thomas A. Edison High School, Johnson moved to New York City with one bag of clothes and $15.

Once in New York, Johnson returned to dressing in clothing made for women and adopted the full name Marsha P. Johnson; the “P” stood for “Pay It No Mind,” a phrase that became her motto. Johnson described herself as a gay person, a transvestite, and a drag queen and used she/her pronouns; the term “transgender” only became commonly used after her death. According to her nephew, Johnson always maintained a close but fraught relationship with her family back in New Jersey.

It was not easy to live on the margins. New York State still persecuted gay people and frequently criminalized their activities and presence. Rights for LGBTQ+ people were limited and sometimes ignored completely. Having difficulty finding employment, Johnson turned to sex work. She was often abused by clients and arrested by the police. She also did not have a permanent home during this time, and bounced around sleeping at friends’ homes, hotels, restaurants, and movie theaters. She also found work waiting tables and performing in drag shows. In a 1992 interview, Johnson said "I was no one, nobody, from Nowheresville until I became a drag queen.”

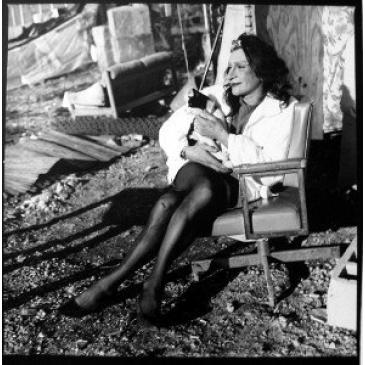

Not long after moving to New York, then 17-year-old Johnson met 11-year-old Sylvia Rivera. Rivera, a Puerto Rican transgender girl, and the two became instant friends. Rivera later said of Johnson, “she was like a mother to me.” As Johnson had done for herself, she encouraged Rivera to love herself and her identity. Johnson adored wearing colorful, fun outfits that she made from finds at thrift stores and discarded items; she was also often seen wearing a crown of flowers.

Johnson’s life changed when she found herself engaging with the resistance at The Stonewall Inn on June 28, 1969. In the early morning hours, police raided the bar and began arresting the patrons, most of whom were gay men. Johnson and Rivera arrived at Stonewall around 2am where, Johnson said in a later interview, “the place was already on fire, and there was a raid already. The riots had already started.” There are many competing stories about what Johnson did during the raid on the Stonewall Inn, but it is clear she was on the front lines. Johnson, like many other transgender women, felt they had nothing to lose. They were not only angered by the police raid but also the oppression and fear they experienced every day. In the wake of the raid, Johnson and Rivera led a series of protests.

The raid on Stonewall galvanized the gay rights movement. The first Gay Pride Parade took place in 1970 and a series of gay rights groups—including the Gay Liberation Front, a more radical organization, and the Gay Activist Alliance, a more moderate and focused spin-off group—emerged. Johnson was involved in the early days of both but grew frustrated by the exclusion of transgender and LGBTQ+ people of color from the movement. She actively spoke out about the transphobia in the early gay rights movement. In 1970, Johnson and Rivera founded Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR), “an organization dedicated to sheltering young transgender individuals who were shunned by their families.” The two also began STAR House, a place where transgender youth could stay and feel safe. STAR House was of personal importance to Johnson and Rivera as they had both spent much of their youth experiencing homelessness and destitution. The first STAR House was in the back of an abandoned truck in Greenwich Village. STAR House then moved to a dilapidated building, which they tried to fix up, but the group was evicted after eight months.

Throughout the 1970s, Johnson became a more visible and prominent member of the gay rights movement. She began performing with the drag group, “Hot Peaches.” She attracted the attention of many, including the pop artist Andy Warhol who included her in a series of prints in 1975 entitled “Ladies and Gentlemen.” In an interview Johnson did for a 1972 book, she said her ambition was “to see gay people liberated and free and to have equal rights that other people have in America.” She wanted to see her “gay brothers and sisters out of jail and on the streets again.” In another interview, she said “as long as gay people don’t have their rights all across America…there is no reason for celebration.” In 1980, she was invited to ride in the lead car of the Gay Pride Parade in New York City.

Despite her joyous personality and ever-present smile, Johnson experienced hardship. She never let her personal setbacks stop her advocacy. In the 1970s, Johnson experienced a series of mental health breakdowns and spent time in and out of psychiatric hospitals. She also continued to engage in sex work, not knowing any other way to make money, and continued to get arrested. In 1990, Johnson was diagnosed with H.I.V. She spoke publicly about her diagnosis and how people should not be afraid of those with the disease in a June 26, 1992 interview.

On July 6, 1992, Johnson’s body was found in the Hudson River. She was 46. Initially ruled a suicide, many friends questioned that conclusion and suspected foul play. At the time, 1992 was the worst year on record for anti-LGBTQ violence according to the New York Anti-Violence Project. Police then reclassified the case as a drowning from undetermined cause, but the LGBTQ+ community was furious that the police refused to investigate further and that many press outlets did not cover her death. At her funeral, hundreds of people showed up at the church; it was so crowded that people stood on the street. In 2012, the New York Police Department reopened the case into Johnson’s death.

In 2019, New York City announced that Marsha P. Johnson, along with Rivera, would be the subject of a monument commissioned by the Public Arts Campaign “She Built NYC.” The monument will be the first in NYC to honor transgender women. In 2020, New York State named a waterfront park in Brooklyn for Johnson. Johnson is also now the subject of many documentaries. She remains one of the most recognized and admired LGBTQ+ advocates.

Susan Devaney, “Marsha P Johnson’s Activism Matters Now More than Ever,” Vogue UK, June 6, 2020, https://www.vogue.co.uk/arts-and-lifestyle/article/who-was-marsha-p-johnson

Meilan Solly, “New York City Monument Will Honor Transgender Activists Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera,” Smithsonian Magazine, June 3, 2019, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/new-york-city-monument-will-honor-transgender-activists-marsha-p-johnson-and-sylvia-rivera-180972326/

Hugh Ryan, “Power to the People: Exploring Marsha P. Johnsons Queer Liberation,” Out, August 24, 2017, https://www.out.com/out-exclusives/2017/8/24/power-people-exploring-marsha-p-johnsons-queer-liberation

Sewall Chan, “Marsha P. Johnson,” Overlooked, The New York Times, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/obituaries/overlooked-marsha-p-johnson.html?mtrref=&mtrref=undefined&gwh=7FAC77AD0450CB8215713140B8184F62&gwt=regi&assetType=REGIWALL

“Life Story: Marsha P. Johnson (1945-1992),” Women & the American Story, New-York Historical Society, https://wams.nyhistory.org/growth-and-turmoil/growing-tensions/marsha-p-johnson/#:~:text=After%20graduating%20high%20school%2C%20Marsha,to%20questions%20about%20her%20gender.

MLA – Rothberg, Emma. “Marsha P. Johnson.” National Women’s History Museum, 2022. Date accessed.

Chicago – Rothberg, Emma. “Marsha P. Johnson.” National Women’s History Museum. 2022. www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/marsha-p-johnson

Image Credit: Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Ron Simmons.

Emma Rothberg, “Sylvia Rivera,” National Women’s History Museum, 2021. www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/Sylvia-Rivera.

Jen Carlson, “Activists Install Marsha P. Johnson Monument in Christopher Park,” Gothamist, August 25, 2021, https://gothamist.com/arts-entertainment/marsha-p-johnson-statue-bust-christopher-park

The Marsha P. Johnson Institute, https://marshap.org/