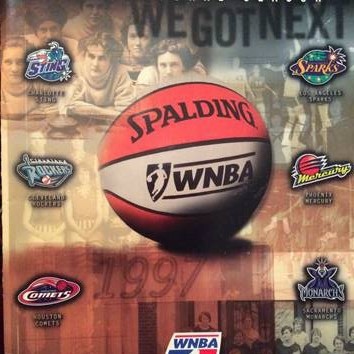

"We Got Next!"

Cecilia Zandalasini of the Minnesota Lynx attempts a 3-point shot as Breanna Stewart of the Seattle Storm defends.

On June 21st, 1997, Lisa Leslie, center for the Los Angeles Sparks, and Kym Hampton, center for the New York Liberty, took the ceremonial "jump ball" marking the official start of the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA). Leslie, 25, had just earned an Olympic gold medal as part of the 1996 US National team. Hampton, who’d graduated from Arizona State University in 1984, had spent the last twelve years playing professional basketball in Spain, Italy, France, and Japan. Between the two stood league president Val Ackerman. A four-year starter at the University of Virginia, in 1977 Ackerman had been one of school's first female students to receive an athletic scholarship.

As the orange and oatmeal-paneled ball was tossed into the air, their names were added to the ever-expanding road of women’s basketball history. Retracing their route backwards through time, you would see the first NCAA women’s basketball champions, Louisiana Tech (1982), pass the Women’s Basketball League of 1979-81, and pause for a visit with the Mighty Macs of tiny Immaculata University (Malvern, PA), winners of the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women’s first collegiate basketball championship (1972). Next, you’d circle the major road marker of Title IX of the Educational Amendments Act of 1972, which revitalized and revolutionized women’s college athletics. Further down the road would be the legacy of US National Teams in the 50’s, and 60’s and the "industrial teams" of 1930’s and 40’s sponsored by companies such as Maytag and Hanes Hosiery. Avoiding the Women’s Division of the National Amateur Athletic Federation’s attempt to strangle the sport in the late ‘20s by eliminating high school tournaments, a final exhilarating zig-zag through the nationwide explosion of the game’s popularity in the 1900’s would find you at the starting place: a gym at Smith College in 1892, right down the road from the birthplace of men’s basketball, Springfield, MA.

The WNBA’s birth is rooted in that history, weighed down by forces that have sought to stifle the existence of women’s team sports, and inspired by men and women who believed that women could and should play in a professional league in the United States.

Fueled by the Flame

Becky Hammon of the San Antonio Stars drives against Yelena Leuchanka of the Atlanta Dream.

The WNBA grew out of a disappointment. Having climbed to the peak of international play with gold medals in the ’84 and ’88 Olympics, the US National team was stunned by a bronze medal finish in the '94 World Championship. With Atlanta set to host in 1996, the Olympic Committee was determined to recapture gold. In 1995, they tapped Stanford’s three-time NCAA National Coach of the Year Tara VanDerveer as head coach and committed to funding a yearlong training camp. The team’s 52-game schedule included tours of Russia, Ukraine, China, Australia, and Canada as well as matchups against top women’s college programs. Extensive media coverage raised the profile of the team as a whole and, in particular, its stars: the elegant center Leslie, the silky-smooth shooter Sheryl Swoopes, and college sensation Rebecca Lobo, who had just won the 1995 NCAA championship with the upstart Connecticut Huskies. The team handled the pressure with aplomb, dominated the competition, and earned a gold medal.

Their success dovetailed perfectly with NBA president David Stern’s plans to expand his league’s model, which included launching a pro league for women. Ackerman, who had been hired in 1988 as a staff attorney for the NBA, and later was promoted to vice-president of business affairs, was appointed to head the WNBA in 1996. "We didn’t go off a lot of data," Ackerman said. "David would call it informed impulsiveness. It felt right, time seems right, he’s been thinking about it for a long time. Business is good for the NBA, let’s go."

Adding the W to NBA

Sue Bird of the Seattle Storm, June 28, 2010.

Leslie, Swoopes, and Lobo became the marketing face of the league under the "We Got Next" campaign. Framed as a summer league, the WNBA featured eight teams: the Charlotte Sting, Cleveland Rockers, Houston Comets, and New York Liberty in the Eastern Conference. The Los Angeles Sparks, Phoenix Mercury, Sacramento Monarchs, and Utah Starzz were in the Western Conference. Each team was attached to an NBA team, the logic being they could leverage the organizational structures already in space: high quality arenas, marketing and support staff, and connections to an established fan base and local media presence. A short 28-game season avoided competing with established professional men’s leagues and allowed players to augment their salaries by continuing to play abroad.

The rules and equipment were similar to the NBA, with the major differences being two 20-minute halves (currently the WNBA plays 10-minute quarters), a shorter three-point line and a slightly smaller ball. Sponsors such as Budweiser and Lee were signed, Champion designed uniforms, Pinnacle was contracted to produce player trading cards, and the league was off and running.

The Game

Tina Charles of the Connecticut Sun and Leilani Mitchell of the New York Liberty, June 27, 2010.

The Houston Comets won the first four WNBA titles and featured the league’s first "Big Three:" Swoopes, Tina Thompson, and Cynthia Cooper. Cooper, with her signature "Raise the Roof" celebration, was a revelation. After spending a decade playing abroad, the 34-year-old entered the league and dominated. She was a two time league MVP (1997, 1998), three-timeWNBA scoring champion (1997-1999), and four-time All-WNBA First Team (1997-2000). In a 20th anniversary league retrospective, Mechelle Voepel wrote: "Early on, no player was more important to the WNBA than Cynthia Cooper-Dyke. She showed women's basketball fans in the United States what they had been missing while she played overseas. And she made them grateful that the WNBA came along in time for her to do that."

As multiple championships moved through teams in Los Angeles, Phoenix, Detroit, Seattle, and Minnesota, individual players began to make their mark with a combination of talent and personality: Teresa Weatherspoon’s passion, Tina Thompson's "ready for battle" lipstick, Leslie's famously sharp elbows, Australia’s fierce Michelle Timms, Deanna Nolan's pogo-stick-like elevation, Yolanda Griffith's crushing relentlessness, Ticha Penicheiro's magical passing, Becky Hammon's fearless acrobatics, Debbie Black’s gnat-like defense, Lauren Jackson’s "guard-in-the-body-of-a-big" play, Sue Bird's signature pull-up, Tamika Catching's peerless work ethic, Diana Taurasi's dagger-threes, Candace Parker's multi-position play, Maya Moore’s stubborn elegance, Elena Delle Donne's fluid shot-making and, most recently, Breanna Stewart's Go-Go Gadget arsenal.

Growing and Growing Pains

Swin Cash of the Seattle Storm defends Diana Taurasi of the Phoenix Murcury.

When the WNBA opened its doors, they made conservative estimates at attendance. Instead, they saw arenas full of passionate fans—some who’d followed women’s college basketball for years, some who were brand new to the game, all drawn by the excitement of watching a women’s team sport. The enthusiasm fueled optimism and expansion, with the league doubling in size to 16 teams by 2000. But, while tickets were priced affordably, especially compared to men’s professional leagues, and drew a diverse demographic of fans, not every WNBA team was a popular success, nor was every NBA owner or organization committed to the supporting their sister team.

The NBA owned each of the franchises until 2002, when it opened ownership groups in cities with and without NBA teams. As a result, the league has seen teams relocate and fold—most shockingly the Comets in 2008. There have been a total of 18 franchises in WNBA history and the current total stands at 12, seven of which are owned independently: Atlanta Dream, Chicago Sky, Connecticut Sun, Dallas Wings, Las Vegas Aces, Los Angeles Sparks, and Seattle Storm. Teams with an NBA connection are the New York Liberty, Indiana Fever, Minnesota Lynx, Phoenix Mercury, and Washington Mystics. The WNBA now plays a 34-games regular season plus an All-Star game. For post-season play, the league has expanded from the ’97 Championship three games (four teams playing a single elimination games) to the current structure in which eight playoff bids are earned by the best end-of season records. In 2018, the format included two single-elimination wild-card games and a best-of-five series for the semi-finals and finals.

Speed Bumps

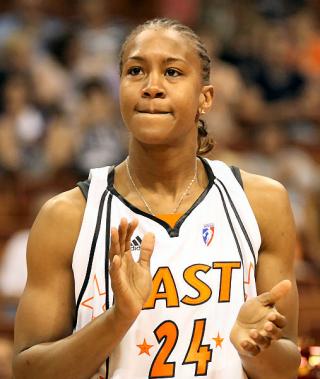

Tamika Catchings of the Indiana Fever at the WNBA All-Star Game.

Fueled by the growth of the women’s game at the NCAA level, the speed, skill, and athleticism of play has grown exponentially. In the inaugural season, WNBA teams averaged 69.2 points per game. In 2018, that number was 82.8. The 22nd year—one many are calling the best ever—has seen personal and league records fall and the arrival of a stellar rookie class. But, a high-quality product on the court has yet to translate into big revenue, as carving out space in the professional sports landscape has proven to be a challenge. The small number of teams and short season has made consistent local or national media coverage—especially in the age of shrinking newsrooms—a struggle. Small internet "startups" created by fans and independent journalists have tried to fill the gaps by both aggregating traditional media as well as providing additional coverage.

Television broadcast rights have bounced between providers, starting with NBC before the league transferred the rights to ABC/ESPN. In 2007, the WNBA and ESPN came to an eight-year television agreement, which was the first to pay television rights fees to the league's teams. A six-year extension extends coverage through 2022, but the games have limited audience exposure as they are often relegated to ESPN2, the WatchESPN app, and, as in the case of this year’s Finals, ESPNews—a channel many cable subscribers didn’t have. To expand access to games, the league launched "Live Access" (now "League Pass") in 2009 to stream games for a small annual fee. In 2017, Twitter announced a deal with the league to stream 20 regular-season games per year in 2017, 2018, and 2019.

While attendance has plateaued at about 6700 a game, current president Lisa Borders is actively seeking to expand revenue streams through sponsorship agreements, most obviously logo placement on jerseys. Most recently, the WNBA joined the fantasy sports market in partnership with FanDuel, and in 2018 the league entered the video game arena as part of the EA Sports’ NBA Live franchise.

Elephants in the Road

Ivory Latta of the Atlanta Dream, September 18, 2009.

It is impossible to discuss women’s athletics without acknowledging the ongoing battle against of sexism, racism, and homophobia, both within and without the league. When the WNBA opened play, it was obvious there was a strong gay community within the fan base. With players being very fan-friendly, it became common knowledge that some players were in same-sex relationships. Yet to many is seemed that the league had a "don’t ask, don’t tell policy." Heterosexual relationships and marriages of players were celebrated on the league’s website, while annual Pride Day events were selectively acknowledged by franchises. The league’s unspoken fear of alienating sponsors ended up angering many loyal fans—and put pressure on players, who themselves seemed torn about announcing their sexual orientation. For example, in 2002 the Liberty’s Sue Wicks was one of the first WNBA players to come out. Six years later, she reflected "I thought there was too much attention on it and it was taking away from my team and the focus on basketball. It wasn’t that I didn’t think it was amazingly important—it was. [But] I was, first and foremost, a member of a team, and I had obligations to fulfill to them."

Times have shifted, and both the league and players have embraced openness. Lynx star Seimone Augustus shared her wedding photos online, as did the Mercury’s Diana Taurasi. Seattle’s Sue Bird’s relationship with US soccer star Meghan Rapinoe has made them a "super couple" in the state of Washington. Several gay players have publicly welcomed children into their lives and the WNBA, as well as media and broadcasters, have begun to include that information as "par for the course" player background.

Sexism, too, has dogged the game, especially online in the form of so-called "trolls." Hateful and vile language commonly seen in comment sections of women’s basketball coverage has been amplified by popular social media platforms. Current players, though, seem unafraid of using their media savvy to slap back and work to change the narrative. Witness Phoenix Mercury’s Devereaux Peters, whose pithy and humorous takedown of naysayers on Twitter became an opinion piece in the Washington Post, "I’m a WNBA player. Men won’t stop challenging me to play one-on-one."

Overall, players are embracing the role of athlete-activist. In the past three years, the Minnesota Lynx players wore "I Can’t Breathe" t-shirts in support of #BlackLivesMatter, the Atlanta Dream’s Layshia Clarendon, self-identifying as gender nonconforming, has become an outspoken LGBTQ+ advocate, and Seattle’s Breanna Stewart, after penning a #MeToo article, has become a spokeswoman for RAINN, the nation's largest anti-sexual violence organization. The league has followed suit, if a tad more slowly, as exemplified by the 2018 "Take A Seat, Take A Stand" campaign. "For each ticket purchased," stated the league release, "the WNBA will donate $5 to one of six organizations of the fans’ choosing [Support Bright Pink, GLSEN, It’s On Us, MENTOR, Planned Parenthood and The United State of Women]."

SPEEDING TOWARDS 25

Cappie Pondexter of the New York Liberty, July 8, 2012.

As the WNBA prepares to move into its 23rd season, the future seems bright, but it is in no way guaranteed. Throughout its history, the league has been secretive about its finances and demanded a lean budget. Teams fly coach, and salaries for the four-month season are modest: on average, WNBA players make just over$70,000. This past season, there has been a very public push by star players to increase salaries, improve travel methods, and create a schedule that is less compressed. With a new Collective Bargaining Agreement on the horizon, there is a call for greater transparency and action. Whether players will get either is up for discussion—and likely dependent on an honest look at the bottom line.

While 2018 has seen an upsurge of media attention—some from traditional outlets, some from newly created on-line sources—it is unclear what leverage the league has with their broadcast partner ESPN. Some franchises are thriving, while others are in limbo. What is clear is that as the on-court talent rises, it is supported by a growing and recognizable off-court presence. The earlier generations of players have returned to coach in the NCAA, WNBA, and NBA. They’ve become the face of the game through broadcasting, joining the league as administrators, publishing books and building businesses in their communities. 1997’s mantra "We Got Next" has evolved into "We Demand and Deserve More."

Helen Wheelock’s love for women’s basketball started in 1997 when a friend walked her into Madison Square Garden for her first Liberty basketball game. Since then, she’s spent hours boning up on women’s basketball history. In 2000, she started writing about the sport for various organization including thehoopslink.com, Women’s Basketball Magazine, the Women’s Basketball Coaches Association, and the Women’s Sports Foundation. Currently she manages the WomensHoopsBlog. You can find her articles at Unintentional Journalist.